Scholars have long been puzzled by the 819-day cycle of the Maya calendar. However, at this point, this mystery may have found its answer.

Although the Maya civilization is well-known, it remains shrouded in mystery. The Maya were a Native American tribe and the masters of the civilization of the same name, recognized largely for their fully developed writing system even before the first Europeans set foot in the Americas.

Based on the remnants that survive to this day, the Maya kingdom is believed to have begun around the first century AD, but the oldest structures of this civilization are dated to be approximately 1,000 years older. There is still much debate surrounding the exact period of existence of this tribe. The Maya primarily lived through agricultural activities, mainly relying on favorable natural factors such as weather and climate.

Moreover, the remarkable advancements and understanding that the Maya had concerning mathematics, architecture, astronomy, and timekeeping technology have astonished modern scientists. The Maya numbering system was vigesimal (base 20), and they even had the first concept of zero. In terms of astronomy, there is clear evidence in architecture, culture, and art that the Maya had profound insights into the movements of the Moon and the Sun.

The Maya civilization was significantly impacted by wars among kingdoms. The last Maya kingdom was destroyed in the 16th century prior to the Spanish invasion.

In recent years, scientists and archaeologists have focused on various aspects of Maya society, including their magnificent architectural structures and complex deities. However, one of the most elusive aspects of this ancient culture is their 819-day calendar cycle.

According to a new study by Professors John H. Linden and Victoria R. Bricker from Tulane University published in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica, previous investigations were on the right track in suggesting that this calendar was linked and synchronized with the period a planet requires to return to the same position in the sky relative to the Sun, as viewed from Earth. However, the key to fully understanding it is to consider it within a much larger timeframe.

Their research shows that the Maya calendar aligns with planetary cycles over a period of 45 years—a much broader timeframe than previously speculated.

The authors explain: “While previous studies have attempted to indicate relationships between planets within the total of 819 days, its four-part color orientation scheme is too brief to align with the synodic periods of observable planets.”

The Maya are renowned for their impressive advancements and profound understanding of astronomy and mathematics. These advancements are deeply reflected in how this civilization calculated time and their calendar-making technology.

The solution to this mystery is based on the numerical values at the core of the Maya numeral system, which is vigesimal (base 20).

“By extending the length of the calendar to 20 cycles of 819 days, a pattern emerges that shows the synodic periods of all visible planets align with the checkpoints in the larger 819-day calendar.”

Thus, the Maya charted a period of 45 years (comprising 20 sets of 819 days) representing the alignment of the planets, turning it into a calendar. The complexity of the 819-day cycle lies in the correlation between planets moving at different speeds; however, when examined over 20 cycles (equivalent to about 16,380 days or 45 years), the synodic periods of the planets perfectly align with the calendar.

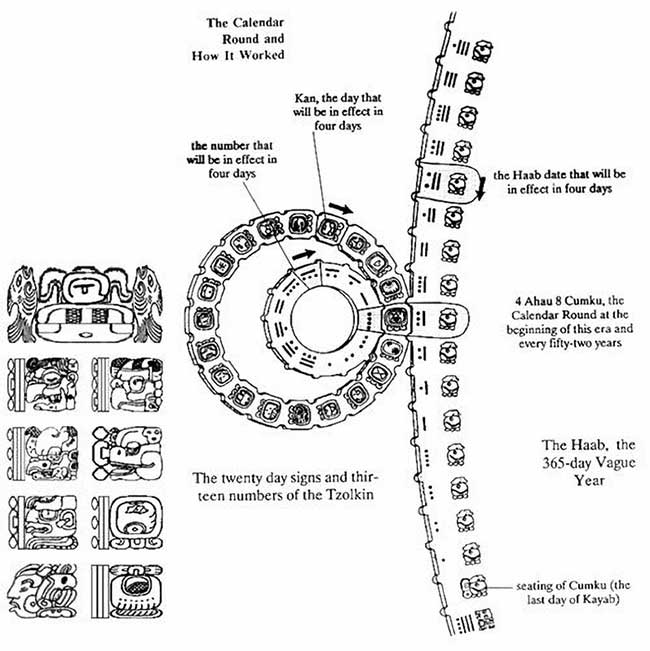

The Maya did not just have a single calendar; they created many calendars tailored for different purposes of timekeeping: for agriculture, rituals, and more. Specifically, the Maya accurately calculated a year to be 365 and 1/4 days. Each Maya year was divided into 18 months, each with 20 days and named individually, along with 5 days “not belonging to any year” at the year’s end, known as Wayeb, which were considered extremely dangerous days. This method of timekeeping is known by the Maya as Haab.

The Maya had incredibly precise measurements of the synodic periods of observable planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

The initial factor in this puzzle was always the 117-day synodic cycle of Mercury, but when charting 20 cycles, all planets fall into place within the calendar. The total length can be determined by Mars, which has a synodic cycle of 780 days, perfectly aligning with 21 cycles adding up to 16,380 or 20 cycles of 819 days. Venus requires seven cycles to match five counts of 819 days, Saturn needs 13 cycles to align with six counts of 819 days, while Jupiter requires 39 cycles to achieve 19 counts of 819 days, according to the Universal Mechanism.

Overall, this discovery indicates that the Maya civilization possessed complex mathematics and meticulous astronomical observations long before modern science developed.

“Rather than limiting their focus to any single planet,” the authors conclude, “Maya astronomers, who created the 819-day counter, envisioned it as part of a larger calendar system that could be used to predict all cycles of visible planets, corresponding to their cycles within the Tzolk’in and Calendar Round.”