If you are familiar with the adventure of Albert Einstein’s brain after his death, then here is a similar story about the skull of René Descartes. The fame of both brilliant scholars has turned their remains into targets for grave robbers.

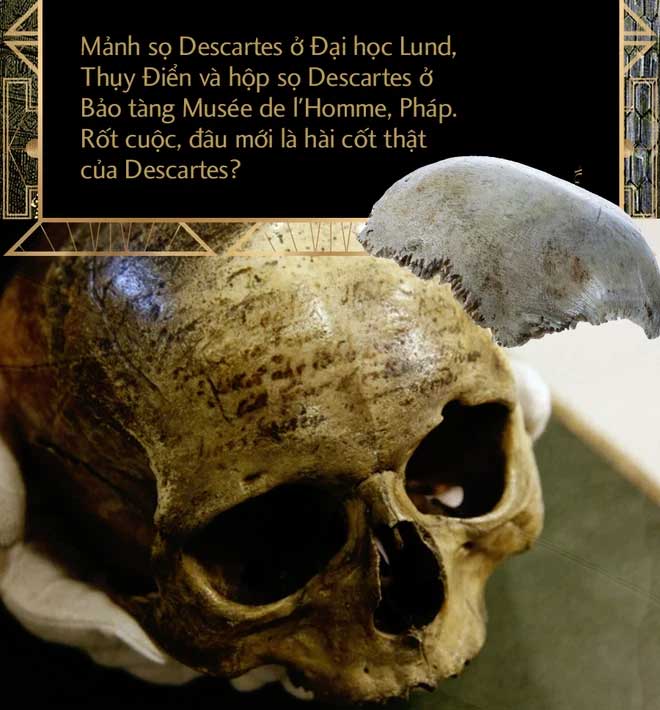

In the case of Descartes’ skull, the chaotic and overlapping accounts of its fate have left us unsure of which is truly his: the specimen displayed intact and reverently at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, or the fragmented pieces scattered in rare collections around the world?

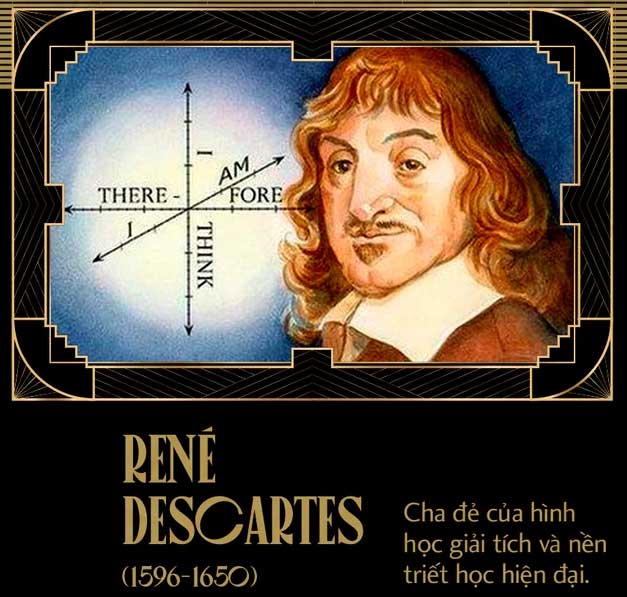

In case you have forgotten, René Descartes was a French mathematician who lived in the 17th century, the founder of analytic geometry, the inventor of the coordinate axes Ox and Oy to describe geometry algebraically, and the first to use the notation x² to denote squares—knowledge you are likely familiar with from high school.

Additionally, with his famous phrase “I think, therefore I am,” Descartes is also considered the father of modern philosophy. He was one of the key figures contributing to the Scientific Revolution and had a significant influence on the physicist Isaac Newton from a young age.

The Missing Skull in the Coffin

The story of Descartes’ skull naturally begins after his death. In 1649, when Descartes had become the most renowned mathematician, scientist, and philosopher in Europe, Queen Christina of Sweden invited him to her court to establish a new scientific academy.

Here, Descartes held presentations before the Swedish court and gave private lectures for the Queen. Unfortunately, in early February 1650, Descartes suddenly fell ill and died about 10 days later.

His death remains a topic of much debate. Theodor Ebert, a German philosopher, suggested that Descartes was poisoned by Catholic preachers in Sweden who disagreed with the religious views he presented to the royal family.

However, according to mainstream accounts, Descartes simply died of pneumonia. After his death, his body was buried in Stockholm, in a small cemetery designated for Catholics, primarily containing the graves of orphaned children.

What happened next depends on which story you believe, but one thing historians agree on is that Descartes’ skull did not rest in peace. According to the most widely accepted records, his grave in Stockholm was exhumed in 1666 after a campaign by his compatriots who wanted to bring his remains back to France.

Descartes’ remains were then reburied in the church of Saint-Geneviève-du-Mont in Paris, but they only rested for a little over 200 years before being exhumed again in the 19th century during a brief period of political chaos in France.

His remains were relocated to ensure their safety. However, before being reburied in 1818, his coffin was opened, and the first people to look inside were shocked to find Descartes’ skull missing.

Jöns Jakob Berzelius, one of the pioneering chemists from Sweden, was present and confirmed that moment when Descartes’ skull was no longer in the coffin. Upon returning home to Stockholm in 1821, Berzelius later learned that the skull believed to be Descartes’ had been purchased by a gambling tycoon at an auction.

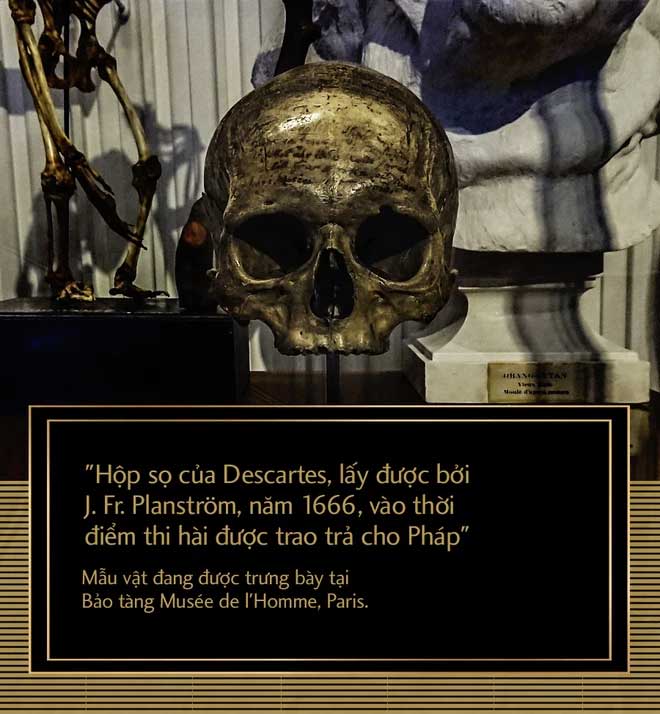

Berzelius persuaded this individual to sell the skull back to him to return it to France. According to Berzelius’s description, this skull was indeed Descartes’, as someone had written on its forehead a Swedish inscription: “The skull of Descartes, acquired by J. Fr. Planström, 1666, at the time the remains were returned to France“.

But why was the skull here? A librarian at the French National Academy of Sciences collected evidence and pieced together a complete story explaining this.

The first link in the chain of events is the question: Who is J. Fr. Planström, who claimed to have stolen Descartes’ skull? It turns out he was one of the guards assigned to watch over Descartes’ remains in 1666 before they were returned to the French.

It is unknown why Planström stole Descartes’ skull, but this guard later died with a mountain of unpaid debts. One of his creditors was a brewery owner in Stockholm, who then took the skull as compensation.

Then the brewery owner died, and Descartes’ skull was passed down to his son. It continued to change hands among various collectors and oddity enthusiasts, who not only appraised the skull but also inscribed their names, sometimes even poetry, onto it.

Eventually, the skull believed to be Descartes’ ended up in the collection of scientist and explorer Anders Sparrman. In 1820, Sparrman died, and the treasures he collected were put up for auction. This is when the gambling tycoon in Sweden acquired the skull, and later, Berzelius approached him to buy it back.

This transaction ultimately succeeded, and Descartes’ skull was returned to France by Berzelius as promised. It is now displayed at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris in a glass case under the theme of humanity. Thus, to this day, it is believed that Descartes’ skull has finally found peace.

But is it really Descartes’ skull?

The question was raised by Per Karsten, director of the History Museum at Lund University, Sweden. In 2020, Karsten and his colleague, archaeologist Andreas Manhag, published an investigation into the origins of Descartes’ skull, based on evidence that the History Museum at Lund University also held a piece of skull believed to be Descartes’, but it did not match the skull in Paris.

Karsten and Manhag argued that the skull at the Musée de l’Homme is actually a fake of Descartes’, due to the names inscribed on it. Of the six names carved on the skull, four are unverifiable.

“It is completely impossible that these individuals ever owned Descartes’ skull,” Karsten and Manhag stated. For example, one of the names the duo could verify is Olof Celsius, a Swedish bishop who lived in the 18th century. Among all the documents regarding this bishop, there is no record indicating that Celsius ever owned Descartes’ skull.

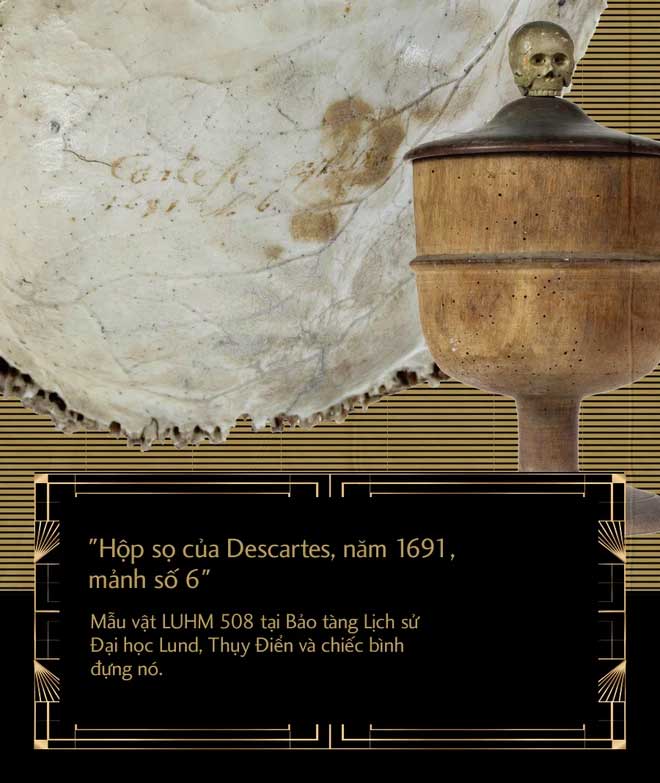

Instead, Karsten and Manhag found another clue. Celsius’s wife, Andreetta Katarina, was reported to have inherited a piece of human skull in 1780. This piece of skull had inscribed the words “Cartesi – döskalla 1691. Number 6“, meaning this is Descartes’ skull, from the year 1691, and it is piece number 6.

It was placed in a strange cup made entirely of wood, with a human skull decoration carved on the lid. “This is the vessel of Mr. Descartes,” Karsten said. Katarina later gifted this piece of skull to Lund University. There, it is regarded as a scientific artifact and marked with the identifier LUHM 508.

According to Karsten and Manhag, the inscription on the LUHM 508 skull piece is more reliable than the inscriptions on the complete skull believed to be Descartes’ in Paris. This is because the year 1691 is not mentioned in any documents related to Descartes.

If someone wanted to forge the philosopher’s skull, “they probably should have chosen the year of death, the year of exhumation, or some similar milestone,” Manhag said. And this may be precisely what the forger of Descartes’ skull in Paris did.

In fact, this forger even managed to dig up information that Olof Celsius was somehow related to the skull, so they inscribed his name on it as an owner. But they did not know that Celsius’s wife was the actual owner of the genuine piece of Descartes’ skull and had gifted it to Lund University personally, with Celsius having no connection to it.

“We know the skull in Paris is a fake, and all evidence so far suggests that the skull piece we hold is real, the piece that Andreetta Celsius donated to our university,” Karsten said.

Regarding the year 1691, according to Manhag and Karsten, it was the year Descartes’ skull was thought to have been blown apart into many pieces, and Andreetta acquired piece number 6 of it, meaning there are still many other pieces of Descartes’ skull.

This aligns with some historical records from Sweden that Manhag and Karsten have collected, which describe many pieces of skull believed to be Descartes’ that were bought and sold in private collections in the 18th century. Importantly, these documents state that Descartes’ skull existed in fragments rather than being intact as a complete skull.

Was Descartes’ skull blown apart?

Based on the recorded documents, Karsten and Manhag agree that it is very likely that the guard named Planström took Descartes’ skull while he was watching over the scientist’s remains in 1666.

The motive behind his actions was that he was drowning in a sea of debt. He wanted to steal the skull of Descartes and sell it to collectors of rare curiosities in Europe during that time.

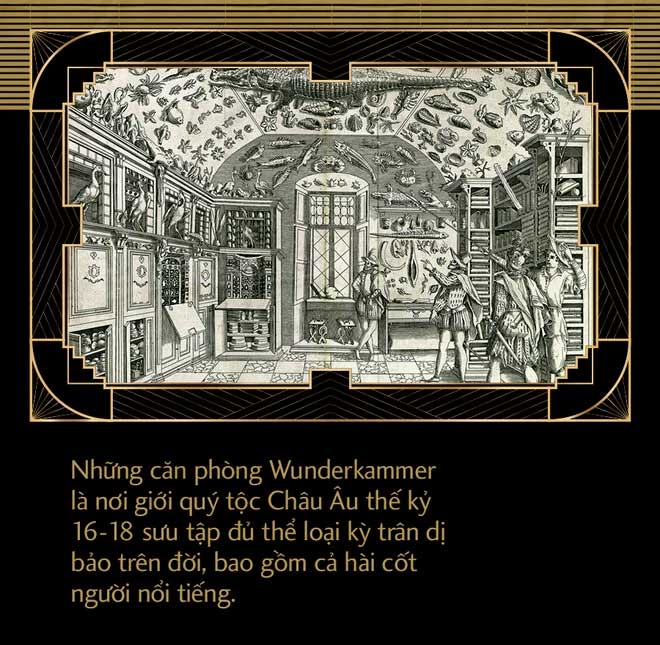

At the end of the 16th century in Europe, as humanism and the interest in studying the natural world flourished, a movement known as Wunderkammer — translated from German as “the cabinet of wonders” — began to emerge among royalty.

Royal members often built themselves a room to collect scientific instruments, charts, mathematical tools, and everything they deemed valuable, reflecting intellect as well as enlightenment.

These Wunderkammer rooms showcased royal power, demonstrating the owner’s authority over the natural world and human knowledge. The Wunderkammer also reinforced the ruling status of its owner.

Gradually, what was favored by royalty trickled down to the nobility. “By the 18th century, the wealthy wanted to own something to showcase in their home libraries,” Karsten said.

The Wunderkammer collections began to expand to include odd items such as bones, mummies, and particularly human skulls, due to the long-standing aesthetic beliefs that a skull preserved not only the identity but also the soul of the person.

The skull of Descartes was stolen by Planström in such a context. And we know he would sell it to nobles who liked to collect. “The trade of famous human remains, opening coffins and stealing bones was very common during that time,” Karsten said.

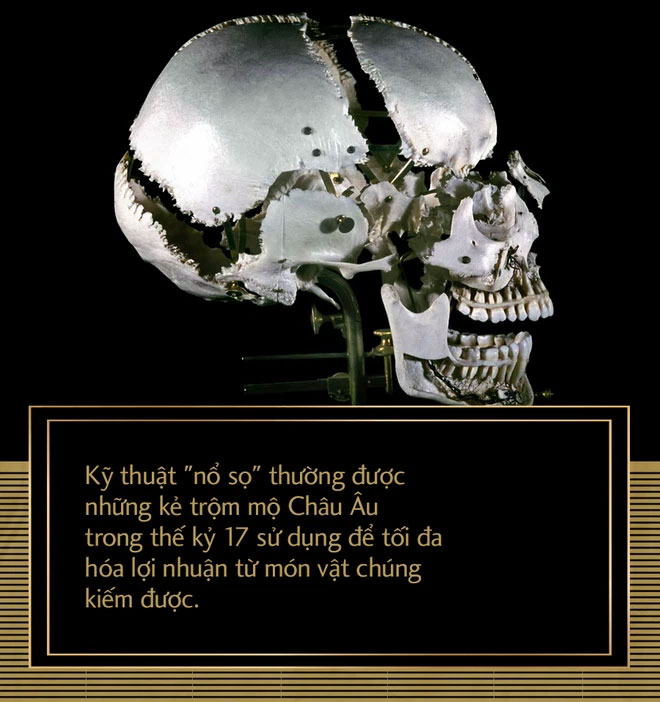

Now, suppose you are Planström and want to sell the stolen skull of Descartes for the highest price. To maximize profits at that time, grave robbers often used a technique known as “skull popping.”

They would turn the skull upside down, place some dried peas inside, which could also be substituted with millet or a handful of rice. Then, they would just add a little water and wait. As the starch absorbed the water and expanded, the collagen-rich tissues holding the skull bones together would weaken.

Eventually, the skull would crack neatly along its fissures. Now, instead of having just one item to sell, they would have six to eight large bone pieces to offer potential buyers.

Indeed, it is unethical and gruesome, but the technique of skull popping was a clever way for grave robbers to maximize profits from the items they found. By an obvious logic, this could very well be what Planström did with the skull of Descartes when he stole the treasure.

DNA Testing Not Conducted, Mystery Will Remain a Mystery

Before the allegations from Lund University in Sweden, the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, which holds the skull, did not comment.

However, Philippe Charlier, a renowned doctor and anthropologist, dubbed by The New York Times as “France’s most famous forensic expert,” conducted examinations on the skull specimen in Paris and concluded: Descartes has come home.

Charlier dismissed the research of Karsten and Manhag, arguing that their claims were baseless. Theoretically, he and his colleagues in France could perform a simple DNA test to settle the dispute. However, they did not do so.

Charlier explained that extracting DNA from bones is always an invasive process, causing damage to the artifact, and the Musée de l’Homme chose not to proceed with it. “They feared the specimen would be damaged, not because they feared the test results,” Charlier said.

And even if the extraction of DNA from the Paris skull were permitted, we might still have nothing to compare it to. Descartes has no living descendants, and his skeleton, reburied in a cemetery in Paris in 1818, has been exposed to water, humidity, and pollutants for centuries. These factors likely degraded the genetic material contained within, and current analyses may not be able to retrieve Descartes’ DNA after more than 200 years.

Therefore, to affirm the results, Charlier’s team conducted several non-invasive tests on the skull of Descartes in Paris. Those tests included a “neuroanatomical analysis” in 2017, using CT scanning methods to model factors in Descartes’ brain structure.

Charlier stated that over the years, “our anthropological and forensic examinations confirm the assessment of sex, age at death, [and] geographical origin” of the Paris skull all match Descartes. He also mentioned that he created a facial reconstruction based on the skull, which closely resembles the portraits of Descartes during his lifetime.

Back at Lund University in Sweden, Karsten still believes that his museum possesses a valuable artifact left by the great Descartes.

“Mr. Descartes has been in Lund since 1780. He is a magnificent symbol of reason, philosophy, and the history of humanity — the emergence of Western scientific thought began with this man — and we have his skull,” Karsten declared.

Manhag seems to be more cautious — at least regarding the authenticity of the skull fragment at Lund. He said: “I am sure that the skull in Paris is a fake. But I cannot be sure that the skull fragment in Lund is real; however, as of now, there is still no evidence to suggest it is also a fake.“

But if the skull fragment number 6 of Descartes in Sweden is real, where are the other pieces of his skull? That is clearly a bigger question for the Museum of History at Lund University. If they want to find credible evidence to affirm their belief, they must locate more skull fragments of Descartes.

It is very likely that they are still scattered somewhere in the Wunderkammer rooms, the rare curiosity collections of European nobility, of which most of us are unaware of their existence.