New Model Research Shows El Niño and La Niña Have Existed for 250 Million Years, Influencing Earth’s Climate

A study conducted by a team of scientists at Duke University, published in PNAS on October 21, reveals that natural global climate phenomena, El Niño and its accompanying cold phase, La Niña, have occurred over the past 250 million years. While these complex weather patterns drive extreme weather changes today, the research indicates that they were significantly stronger in the past.

El Niño (Spanish for “the boy”) and La Niña (the girl) are part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, resulting from ocean temperature variations in the equatorial Pacific. Under normal conditions, trade winds blow westward along the equator, carrying warm water from South America to Asia.

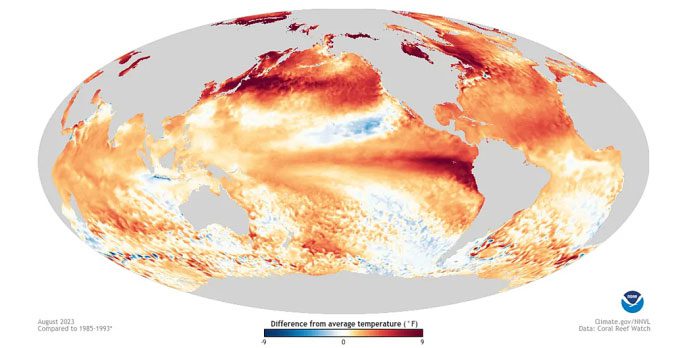

The model indicates that the El Niño-Southern Oscillation phenomenon (which emerged in August 2023) has impacted weather for much longer than previously thought. (Photo: NOAA).

Using climate modeling tools similar to those employed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the research team simulated weather conditions from 250 million years ago. These tools are typically used by climate researchers to predict future developments due to climate change but can also be run backward to examine past events.

Hu and colleagues point out that the intensity of past oscillations depended on two factors: ocean thermal structure and what they refer to as “atmospheric disturbances” of ocean surface winds.

“Therefore, part of our research is that, alongside the ocean thermal structure, we also need to pay attention to atmospheric disturbances and understand how those winds will change,” Hu stated. He noted that in each experiment the team conducted, the El Niño Southern Oscillation was active and “it was almost stronger than what we have now, some stronger, some a little stronger,” Hu added.

The researchers could not model each year in this simulation due to the substantial time span it represents, but they were able to assess conditions in “slices” every 10 million years. The simulation took months to complete but provided a model for thousands of years.

Shineng Hu, assistant professor of climate dynamics at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, stated: “The model experiments were influenced by various boundary conditions, such as different land-sea distributions (with continents in different locations), different solar radiation, and varying CO2 levels.”

At different points in the past, solar radiation reaching the planet was about 2% lower than it is today, but at the same time, CO2 concentrations were higher, causing the atmosphere and oceans to be warmer than they are today.

Notably, 250 million years ago, during the Mesozoic Era, South America was located in the middle of the supercontinent Pangea, and weather oscillations occurred in the west, in Panthalassa—the vast superocean surrounding the expansive landmass.

These simulations are invaluable for understanding how ENSO may operate as climate change continues. This topic has been debated for some time, and previous research has indicated that weather phenomena could become stronger in the future as the climate continues to warm.

Thus, this new research shows that ENSO will be significantly affected in the future due to changes in ocean thermal structure and atmospheric disturbances, along with all the uncertainties that come with it. “If we want a more reliable future forecast, we first need to understand the climate of the past,” Hu said.