According to CNN, the core of glacial sediments originating from the northern part of Greenland has produced the oldest DNA sequences in the world.

These 2-million-year-old DNA samples reveal that the polar regions, which are largely devoid of life today, were once home to a variety of plant and animal species, including mammals such as mastodons, reindeer, hares, lemmings, geese, and birch trees. This research was published in the December 7 issue of the journal Nature.

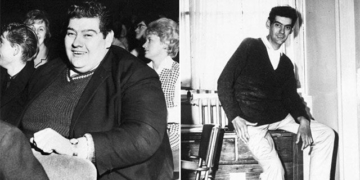

Frozen sediment layer in the Kap Kobenhavn formation in northern Greenland, where scientists discovered the 2-million-year-old DNA samples. (Photo: AFP/TTXVN)

Researchers found that the mixture of temperate and Arctic plant and animal species reflected an ecosystem previously unknown and without a modern equivalent. This ecosystem serves as a genetic map of how species adapted to warmer climates.

During an expedition in 2006, Danish scientists discovered and extracted environmental DNA (the genetic traces left by all living organisms in the environment) from a small amount of sediment taken from a fjord in the Arctic Ocean, at the northernmost point of Greenland. The scientists then compared the DNA fragments with existing DNA data collected from both extinct and extant animals, plants, and microorganisms. This genetic material revealed many plant and other species never before identified at this site.

Co-author of the study, Mikkel Pedersen, an assistant professor at the Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Center at the University of Copenhagen, noted that this data astonished scientists about the presence of mastodons in the far north. This genetic material also broke the previous record for the oldest DNA in the world, which belonged to a study published last year about mammoth teeth from the Siberian steppe over 1 million years ago, as well as the previous record for DNA from sediments.

Professor Eske Willerslev from St John’s College at the University of Cambridge, director of the Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Center, stated that while DNA from animal bones or teeth can shed light on information about a specific species, environmental DNA allows scientists to construct a picture of the entire ecosystem. In this case, the ecological community that researchers reconstructed existed when the regional temperatures were 10 to 17 degrees Celsius warmer than present-day Greenland.

Researchers were surprised to discover that cedar trees similar to those found in British Columbia (Canada) today once grew in the Arctic alongside species such as deciduous pines, which currently grow in the far northern regions of the planet. They did not find DNA from predators but believe that predatory species—such as bears, wolves, or even saber-toothed cats—certainly existed in this ecosystem.

According to Love Dalen, a professor at the Center for Paleobiology at Stockholm University, this discovery indicates the composition of ecosystems at different times, which plays a crucial role in understanding how past climate changes have affected biodiversity at the species level. This is something that animal DNA cannot achieve. He also expressed excitement that the study indicates some temperate species (such as relatives of spruces and mastodons) could survive at such high latitudes.

Professor Willerslev shared that extracting genetic sequences from sediments required significant effort. Researchers noted that the DNA’s self-attachment to mineral surfaces might be why it has persisted for so long.

Further research into environmental DNA from this period could help scientists understand how organisms can adapt to climate change. This is the type of climate humanity will face on Earth due to global warming, and the study will provide insights into how nature will respond to rising temperatures. Accurately understanding this pathway will help humanity support species in adapting to rapidly changing climates.