This process can be utilized to explore an entirely new class of ultralight particles and provide direct information about the mass and state of “gravitational atoms” clouds.

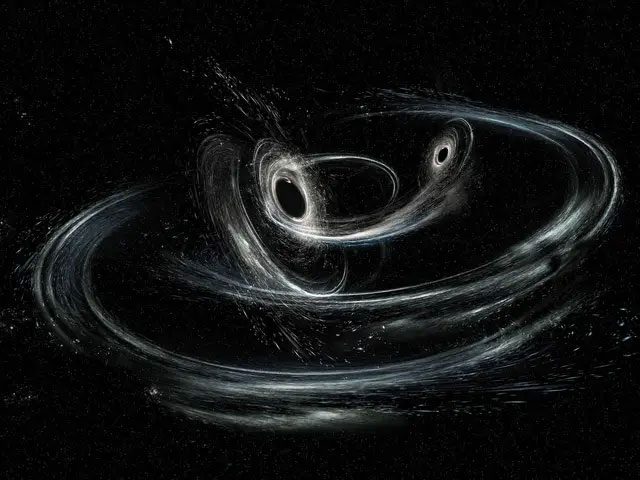

On February 11, 2016, researchers at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. Predicted by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, these waves are the result of massive objects merging, creating detectable ripples in spacetime.

Since then, astronomers have theorized countless ways in which gravitational waves can be used to investigate physics beyond the standard models of gravity and particle physics, enhancing our understanding of the universe.

To date, gravitational waves have been proposed as a means to study dark matter, the interiors of neutron stars, supernovae, mergers of supermassive black holes, and more.

In a recent study, a group of physicists from the University of Amsterdam and Harvard University proposed a method for using gravitational waves to search for ultralight bosons (one of the two fundamental particle types in nature) around rotating black holes. This method not only presents a new way to differentiate the properties of binary black holes but could also lead to the discovery of new particles beyond the Standard Model.

The research was further carried out by researchers at the Amsterdam Gravitational Particle Physics (GRAPPA) in collaboration with the Center for Theoretical Physics and the National Center for Theoretical Sciences at National Taiwan University, and Harvard University. The results of this study were published under the title “Sharp Signals of Boson Clouds in Binary Black Hole Inspiral” in the journal Physical Review Letters.

A well-known fact is that ordinary matter will gradually accrete into black holes over time, forming an accretion disk around their outer edge (also known as the Event Horizon). This disk accelerates to incredible speeds, causing the matter within to become superheated and release a vast amount of radiation while it is slowly accreted onto the black hole’s surface. However, over the past few decades, scientists have observed that black holes lose a portion of their mass through a process known as “superradiance.”

Superradiance, also known as superradiance refers to enhanced radiation effects in contexts including quantum mechanics, astrophysics, and relativity.

This phenomenon was studied by Stephen Hawking, who described how rotating black holes would emit radiation that appears “real” to a nearby observer but “virtual” to someone far away. During the transmission of this radiation from one reference frame to another, the acceleration of the particles themselves causes them to transition from virtual to real. This strange form of energy, known as “Hawking radiation,” forms clouds of low-mass particles around a black hole. This leads to “gravitational atoms,” a term derived from their similarity to ordinary atoms (particle clouds surrounding a core).

While scientists know that this phenomenon occurs, they also understand that it can only be explained by the existence of a new ultralight particle that exists beyond the Standard Model. This is the focus of the new paper, in which lead author Daniel Baumann (GRAPPA and National Taiwan University) and his colleagues examined how superradiance causes unstable ultralight boson clouds to form naturally around black holes. Moreover, they argue that the analogy between gravitational atoms and ordinary atoms goes deeper into their structure.

Gravitational waves are oscillations caused by the curvature of spacetime structure into waveforms propagating outward from the fluctuations of gravitational sources, carrying energy in the form of gravitational radiation.

In summary, they suggest that binary black holes could ionize particles within their clouds through the photoelectric effect. As described by Einstein, this occurs when electromagnetic energy (such as light) interacts with a material, causing it to emit excited electrons (photoelectrons). When applied to a binary black hole, Baumann and his colleagues demonstrated how ultralight boson clouds could absorb “orbital energy” from a “companion” in the black hole. This would result in some bosons being ejected and accelerated.

Ultimately, they proved that this process could significantly alter the evolution of binary black holes. As they state:

“The orbital energy lost in this process can overshadow losses due to GW (Gravitational wave) emission, thus the ionization process drives the evolution not merely by perturbing it. We show that the ionization strength exhibits sharp features leading to a ‘bent path’ in the development of the emitted GW frequency.”

They argue that “these bent paths” will be easily detectable by next-generation gravitational wave interferometers such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA). This process can be used to explore an entirely new class of ultralight particles and provide direct information about the mass and state of “gravitational atom” clouds. In summary, ongoing studies of gravitational waves using more sensitive interferometers may reveal strange physical phenomena that enhance our understanding of black holes and lead to new breakthroughs in particle physics.

In the coming years, astronomers hope to use them to probe the most extreme environments in the universe, such as black holes and neutron stars. They also hope that primordial gravitational waves will reveal insights about the early universe, help resolve the mystery of matter/antimatter imbalance, and lead to a new quantum theory of gravity.