Although the truth about the chess-playing automaton, the Turk, has been revealed, it has not diminished the fascination of the general public.

In the late 18th century, a Hungarian inventor named Wolfgang von Kempelen introduced an extraordinary automaton to Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. It could play chess against any human opponent.

This marvelous machine captivated audiences across Europe and America for over a century, challenging and defeating famous figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. The truth about it sparked much debate at the time.

Famous Chess Player

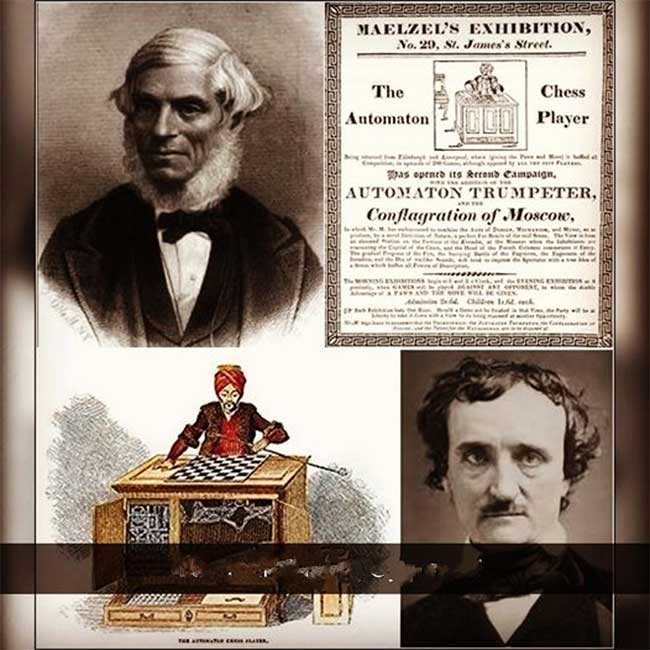

Wolfgang von Kempelen, the creator of the Turk.

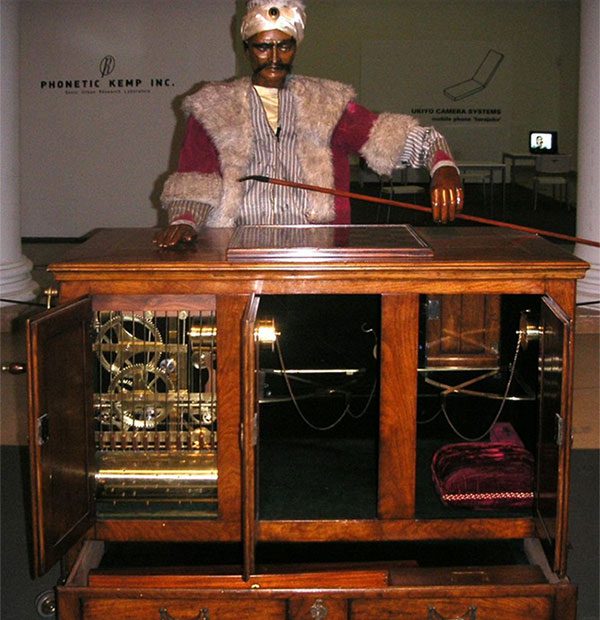

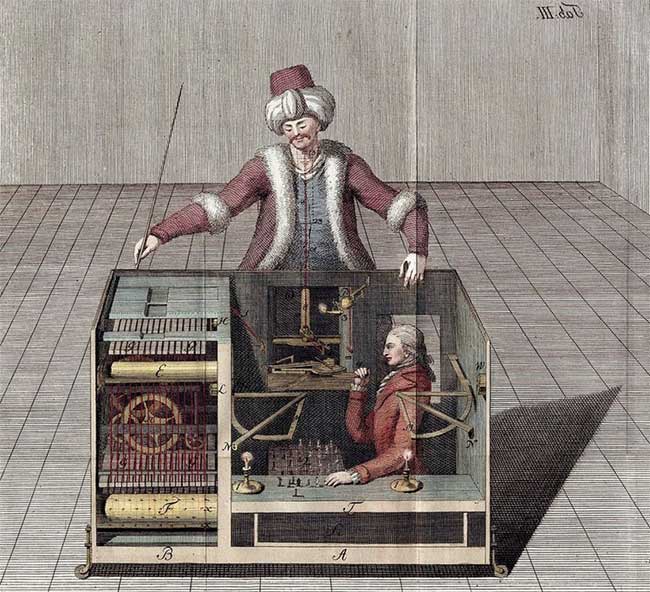

The machine was called the Mechanical Turk, consisting of a large cabinet containing complex machinery, with a chessboard on top. A wooden mannequin dressed in an Ottoman cloak, wearing a turban, sat behind the cabinet. It was also equipped with sound effects to cheer for the matches.

Kempelen began his performance by opening the cabinet doors for the audience to see a complex system of wheels, gears, levers, and thick clockwork. Once the audience was assured that nothing was hidden inside, Kempelen would close the doors, turn the machine with a key, and invite a volunteer to play against the Turk.

The chess game would begin with the Turk making the first move. It would use its left hand to pick up pieces and move them to another square before placing them down. If the opponent made an illegal move, the Turk would shake its head and return the offending piece to its original square.

If the opponent attempted to cheat, as Napoleon did when facing the machine in 1809, the Turk would respond by removing that piece from the board and make its next move. Should the player attempt to violate the rules a third time, the automaton would sweep its arm across the chessboard, knocking all the pieces down, ending the game.

Chess players discovered that the Turk was an exceptionally skilled player, frequently winning matches against competent opponents. During a tour in France in 1783, the Turk faced François-André Danican Philidor, considered the best chess player of his time. Although the Turk lost that time, Philidor described it as the “most exhausting chess match ever” for him.

As the fame of the chess-playing automaton grew, people began to debate how it operated. Some believed Kempelen’s invention had the ability to understand and play chess autonomously…

However, many were skeptical that the machine was, in fact, an elaborate hoax, with the movements of the wooden figure being controlled by Kempelen himself, possibly using magnets or remote wires, or perhaps by a hidden operator inside the cabinet.

One of the most skeptical was English author Philip Thicknesse, who wrote a treatise on the subject titled “The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player – Discovery and Revelation.” However, he did not provide any convincing evidence.

After Kempelen passed away in 1804, his son sold the Turk and its secrets to Johann Nepomuk Malzel, a musician from Bavaria (Germany). Malzel took it on tour across Europe and the United States. Notable writer Edgar Allan Poe saw it perform and wrote a lengthy analysis, speculating on the workings of the automaton.

He suggested that a true machine must win all chess matches and exhibit a characteristic playing style, such as making moves within a fixed time, which the Turk could not do. From this, Poe concluded that the Turk must be operated by a human.

After Malzel died in 1838, the chess-playing automaton was acquired by John Kearsley Mitchell, Edgar Allan Poe’s personal physician and a fan of the Turk. He donated the machine to the Charles Willson Peale Museum in Philadelphia. There, it sat forgotten in a corner until it was destroyed in a fire in 1854.

Advertisement for the chess-playing automaton with famous personalities.

Revealing the Truth

The chess-playing automaton remained a mystery for over 50 years until Silas Mitchell, John Kearsley Mitchell’s son, wrote a series of articles for The Chess Weekly, fully revealing the internal workings of the Turk. Mitchell wrote that, since the Turk had been destroyed, “there was no longer any reason to conceal the solution to this ancient mystery from amateur chess players.”

According to him, the Turk was the trick of a clever magician. Inside the spacious wooden cabinet was an operator, pulling and pushing various levers to make the mannequin above move and play chess.

The owner of the machine could hide the accomplice from view since the door only opened once in front of the audience. In another way, he would sneak inside quickly. The chess pieces had small but strong magnets attached to their bases, which attracted corresponding magnets in the wires below the chessboard and inside the box.

This allowed the operator inside the machine to see which pieces moved where on the chessboard.

Kempelen and the subsequent owner of the Turk, Johann Malzel, chose skilled chess players to secretly operate the machine at various times. When Malzel showed this machine to Napoleon at Schönbrunn Palace in 1809, a German of Austrian descent, Johann Baptist Allgaier, operated the Turk from inside.

In 1818, briefly, Hyacinthe Henri Boncourt, a leading French chess player, became the operator of the Turk. Once, while hiding inside the automaton, Boncourt sneezed, and the audience heard the noise, causing Malzel to quickly find a way to distract them. After that incident, Malzel added some noisy gears to the Turk to mask any sounds that could come from the operator.

When Malzel took the Turk on tour in the United States, he hired European chess player William Schlumberger to operate the machine. After one performance, two boys secretly hiding on the roof saw Schlumberger emerge from the machine.

The next day, a newspaper article in the Baltimore Gazette exposed the incident. Even Edgar Allan Poe noticed that Schlumberger was always missing during the performances but was often seen when the Turk was not competing.

“Furthermore, a few years ago, Malzel visited Richmond with his automaton and displayed it in a house now used by M. Bossieux as an academy of dancing. Schlumberger suddenly fell ill, and during that time there were no chess matches played by the Turk,” Poe wrote.

The Mechanical Turk, illustration from 1789.

Inspiring Inventions

In 1912, Leonardo Torres y Quevedo in Madrid, Spain, created the first truly autonomous chess-playing machine called El Ajedrecista, capable of playing endgames with three pieces without human intervention. It took another 80 years before computers could play an entire game of chess and defeat the best players in the world.

Despite the exposure, the fascination with the Turk chess-playing automaton has not diminished among the general audience. Several scholars studied and wrote about the Turk in the 19th century, including Daniel Willard Fiske, who mentioned chess players and Malzel in his 1857 book titled “The Book of the First American Chess Congress.”

Many other books about the Turk were published in the late 20th century. Surprisingly, by the late 1970s, some authors were still unaware of the true workings of the machine.

In Alex G. Bell’s 1978 book “The Machine Plays Chess,” the author inaccurately claimed that: “the operator was a boy (or a very small person) trained to follow the instructions of a chess player hiding somewhere on stage or in the theater.”

The Turk also inspired several inventions and imitations, such as Ajeeb, a knock-off version of the Turk created by Charles Hooper, an American cabinetmaker, in 1868.

This “knock-off” automaton was showcased across the United States and attracted thousands of spectators to witness its games. Opponents of Ajeeb included Harry Houdini, Theodore Roosevelt, and O. Henry.

When Edmund Cartwright saw the Turk in London in 1784, he was very curious and wondered whether “building a machine that could weave fabric was more difficult than a machine that could perform all the necessary moves in that complex game.” Within a year, Cartwright was granted a patent for his electric loom.

In 1912, Leonardo Torres y Quevedo in Madrid created the first truly autonomous chess-playing machine called El Ajedrecista, which could play to completion with 3 pieces without human intervention. Researchers took another 80 years before computers could play an entire game of chess and defeat the best players in the world.

Illustration depicting the deception of the chess-playing machine.

While modern computers can play chess far better than many famous players, there are still many tasks that humans excel at, such as identifying specific content in images or videos, writing product descriptions, or answering survey questions.

In 2005, Amazon launched a new community service that utilized human labor to perform these tasks. Much like Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk, Amazon’s online service employs remote human workers hidden behind a computer interface to assist employers in completing tasks that cannot be effectively handled by machines.

The service they categorize as “artificial intelligence” is named The Mechanical Turk, or MTurk, after the “automatic chess player” of the 18th century.