In the United States, hurricane hunter aircraft are considered a crucial tool for data collection. As hurricanes approach the coastline, the aircraft dive into the storm and drop an instrument known as a dropsonde.

Hurricane forecasting is likened to a blend of science and art. Meteorological stations combine data from atmospheric pressure sensors, weather balloons, radar, satellites, and reconnaissance aircraft. This information is integrated with computer models to predict the formation location, landfall, and intensity of the storm.

Meteorologist Greg Carbin from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Hurricane Prediction Center states that predicting storms is akin to diagnosing an illness.

“You visit a doctor, describe your symptoms for them to diagnose and provide a prognosis. We need to diagnose the state of the atmosphere as accurately as possible before forecasting,” Carbin shared with Live Science.

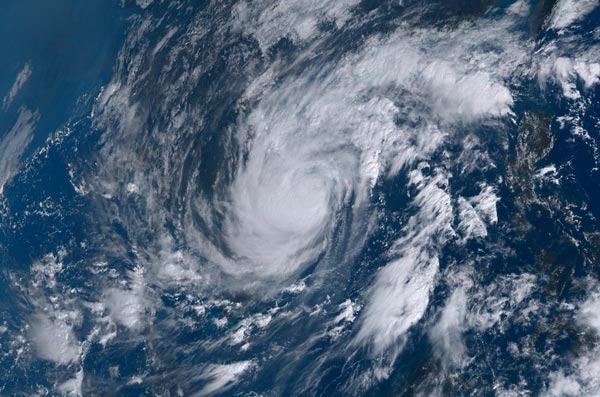

Satellite image of Hurricane Molave (Typhoon No. 9) from Japan’s Himawari 8 satellite. Image: himawari8.nict.go.jp.

Data is a Crucial Element

The forecasting process begins with collecting data on temperature, air pressure, and wind temperature, which is then combined with information from weather balloons to predict weather conditions. Meanwhile, satellites are used to record humidity in the atmosphere and the position of storm clouds.

In Vietnam and several other Asian countries, storms typically originate from the sea and move slowly. Meteorological agencies primarily use data collected from satellites, combined with computer forecasting models to predict the intensity, path, and timing of landfall to formulate timely response and evacuation plans.

In the United States, hurricane hunter aircraft are considered essential tools for data collection. As hurricanes grow closer to the coast, these aircraft plunge into the storm and deploy a device known as a dropsonde.

Deployed from a hurricane hunter aircraft, the dropsonde falls through the storm to collect crucial data. Image: Air & Space Magazine, ABC.

Dubbed the “dark horse in hurricane forecasting,” each dropsonde is equipped with sensors that capture information such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and other critical data. It can record data twice per second under the harshest conditions and is equipped with a parachute to slow its descent.

The data collected from the dropsonde is transmitted back to the research center for analysis, which is then used to create detailed forecasts and stored for future modeling applications. After completing its mission, the dropsonde falls into the ocean.

Using Supercomputers for Hurricane Forecasting

All data acquired from satellites, dropsondes, and weather balloons are fed into a supercomputer system, running through numerous simulation scenarios to produce weather forecasting models. Scientists compare the models from the computer with observational results; if they align, these models are used for predictions.

In Europe, the MareNostrum 4 supercomputer, developed by Lenovo, is utilized in various scientific studies, including weather forecasting and atmospheric research. With a processing power of 11.5 petaflops (11.5 million trillion calculations per second), it can also integrate historical data to provide accurate forecasts for the future.

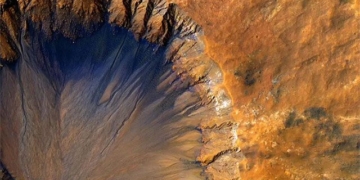

In 2018, scientists from the RIKEN Institute of Physical and Chemical Research in Japan used the K supercomputer to study weather forecasting models, integrating data from the Himawari 8 satellite. This satellite was used to monitor the path of Hurricane Molave (Typhoon No. 9), which made landfall on October 28.

MareNostrum 4 supercomputer located in Spain facilitating scientific research including weather forecasting. Image: Lenovo.

In February, the Washington Post reported that NOAA signed contracts to equip two additional supercomputers to enhance computational capabilities for weather forecasting models. When these systems are operational in 2022, their total processing power will reach 40 petaflops (40 million trillion calculations per second).

The contract, valued at approximately $505 million, aims to help the United States catch up with Europe in the race for supercomputers in terms of accuracy and timeliness of weather forecasts.

In addition to boosting computational power, scientists are also researching improvements to software algorithms to enhance forecasting efficiency.

Peter Bauer, Deputy Director of Research at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), referred to this as a “software gap,” noting that despite having powerful hardware, improving a significant amount of code will take considerable time.

Weather balloon used to gather data over a storm, equipped with sensors to collect information. Image: Los Angeles Daily News.

Dennis Feltgen, spokesperson for the National Hurricane Center (NHC) in the U.S., stated that no model is perfect, so the primary mission is to gather as much data as possible.

“While satellites today can predict weather conditions quite accurately, the paths of storms moving over the ocean are very difficult to forecast. This is why scientists continuously gather as much data as possible to provide better forecasts for upcoming storms,” Feltgen said.

Although it is impossible to prevent hurricanes, effective prediction models with comprehensive information can help people prepare better response plans, reducing damage to life and property.