The heliopause region at the edge of the Solar System has temperatures soaring between 30,000 to 50,000 degrees Celsius, as measured by NASA’s Voyager spacecraft duo.

Heliopause, where the solar wind ceases to have an effect and interstellar space begins, is often referred to as the “Wall of Fire” surrounding the Solar System. This name is not technically accurate, but it highlights a remarkable discovery, which is also one of the major achievements of the Voyager spacecraft.

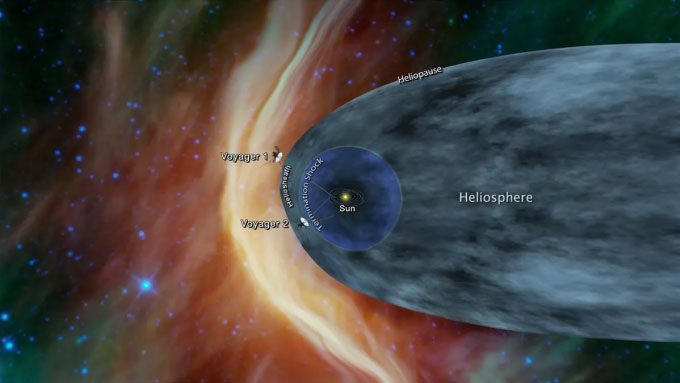

Simulation of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 flying in space. (Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech).

The duo of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were launched into space in 1977. Impressively, Voyager 2 is still operational, while Voyager 1 only lost contact a few months ago, and there is still hope for recovery.

The term “Wall of Fire” is not entirely unfounded. The Voyager spacecraft measured temperatures ranging from 30,000 to 50,000 degrees Celsius as they traversed the heliopause, making fires on Earth seem “cooler” by comparison.

Of course, there is no fire there by traditional definitions: fuel burning by reacting with oxygen. Like the Sun, the heliopause consists of hot plasma. However, passing through the heliopause is not like encountering the Sun. The reason the two Voyager spacecraft do not vaporize is that the density of matter beyond the solar wind’s boundary is extremely low.

To understand why the Wall of Fire is extremely hot despite being far from the Sun and why the spacecraft are unaffected, we first need to grasp the concept of heat. Temperature is a measure of how fast atoms and molecules move. Energy is required to create faster movements. As the speed of movement increases, regardless of the energy source, they are more likely to collide with nearby objects and transfer some energy to that object. Therefore, if you place your hand in a stream of hot gas, the rapidly moving molecules will collide with your hand and cause it to warm up as well.

The fewer the molecules, the less energy is needed to make them move quickly, but the likelihood of them colliding with a solid object that intrudes is also smaller. If such collisions do not occur, energy cannot be transferred, and the intruding object will remain cool.

This is the situation that both Voyager spacecraft and future spacecraft leaving the Solar System will encounter. The heliopause may be denser than the surrounding space, somewhat justifying the term “wall”, but it is still nearly a vacuum. Even when the sparse molecules in that region move very fast at extremely high temperatures, they cannot warm up large objects like the two Voyager spacecraft, each weighing over 700 kg.

So why are these few atoms and molecules so hot despite being far from the Sun? Previously, scientists had predicted that the heliopause would be very hot, but their estimates were only about half of what the Voyager duo actually measured. This also highlights the importance of the Voyager spacecraft in the quest for space exploration.

The exceptionally high temperatures are believed to be due to the compression of plasma when the solar wind meets interstellar space or magnetic reconnection. Reconnection occurs in conductive plasma when the rearrangement of magnetic field structures causes magnetic energy to convert into fast-moving waves, thermal energy, and particle acceleration. Scientists have previously observed magnetic reconnection where the magnetic fields surrounding Earth and other planets encounter solar winds.