Researchers Use Photogrammetry to Reconstruct the Face of a Young Egyptian Man from Ancient Nile Valley.

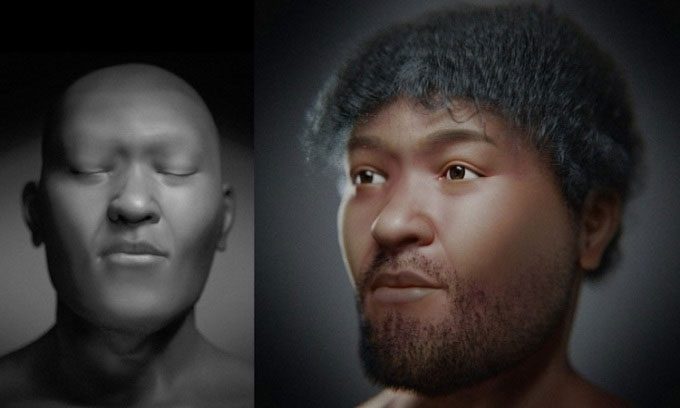

Two reconstructed images of an ancient Egyptian man. (Photo: Moacir Elias Santos & Cícero Moraes)

The reconstructed image of a man who lived 30,000 years ago in Egypt may provide clues about human evolution. In 1980, archaeologists excavated the remains of this man at Nazlet Khater 2, a site in the Nile Valley, Egypt. Anthropological analysis revealed that the man was aged between 17 and 29 at the time of death, stood approximately 160 cm tall, and had ancestry linked to African origins. This skeleton is the oldest Homo sapiens remains in Egypt and among the oldest in the world, according to a study published on March 22. However, experts know very little about the deceased other than that he was buried with a stone axe.

Now, after more than 40 years, a team of Brazilian researchers has reconstructed the man’s face using dozens of digital images they gathered while examining the remains housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, as reported by Live Science on April 3.

According to the lead researcher Moacir Elias Santos, an archaeologist at the Ciro Flamarion Cardoso Museum in Brazil, the skeleton was missing ribs, hands, part of the tibia from both the right and left sides, and feet. However, the main structure for reconstructing the face, the skull, was well-preserved.

A prominent feature of the skull that stood out to researchers was the jawbone, which differs from modern jawbones. Although part of the skull was missing, the research team replicated and simulated it using the other half of the skull and data from a CT scan of a donor. Overall, the skull has a modern structure but still exhibits ancient characteristics, such as a more robust jawbone compared to contemporary males, according to co-author Cícero Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert.

By stitching together images through a digital technique called photogrammetry, the research team created two 3D virtual models of the man. The first model is a black-and-white image with closed eyes, while the second model is more artistic, depicting the young man with tousled dark hair and a neatly trimmed beard.

“What we did was estimate the face using available statistical data, resulting in a very simple structure. However, humanizing the personal face is always important, through adding hair and skin color, which helps stimulate the desire to research more about the subject,” Moraes shared.

The research team hopes that the images of the ancient man will help archaeologists better understand how humans have evolved over time.