Scientists are undertaking an intriguing mission: to revive the European aurochs, a long-lost ancient breed of cattle shrouded in the mists of history.

The bull “Lucio” from the Taurus project and an ancient silver sculpture of an aurochs.

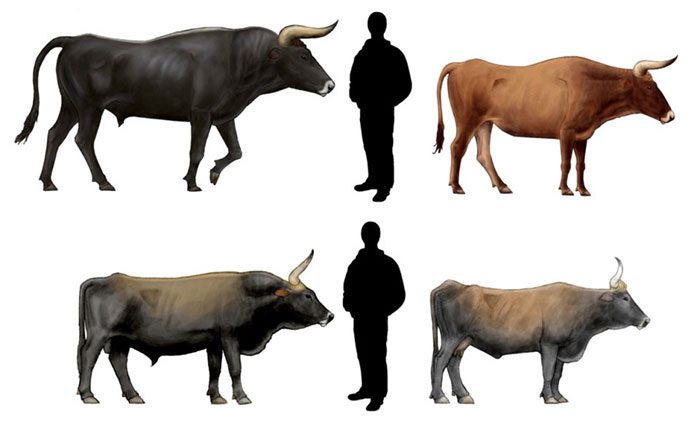

The European aurochs (Bos primigenius) was a massive creature that once roamed the grasslands and forests of Eurasia and North Africa. It is one of the largest herbivores of the Holocene epoch, standing up to 180 cm (71 in) at the shoulder in males and 155 cm (61 in) in females. It had long and wide horns that could reach up to 80 cm (31 in).

The European aurochs was also part of the large animal population of the preceding Pleistocene epoch and is thought to have evolved in Asia before migrating westward and northward during a warm interglacial period.

The European aurochs is one of the largest herbivores of the Holocene. (Illustrative image).

The European aurochs played a significant role in the culture and religion of ancient peoples. It is depicted in Paleolithic cave paintings (such as those in Lascaux and Chauvet caves in France), Neolithic petroglyphs, ancient Egyptian reliefs, and Bronze Age figurines.

It symbolized power, fertility, and strength in the religions of the ancient Near East. Its horns were used as ritualistic implements, trophies, and drinking vessels. The ancient Romans also used this species to pit against their best gladiators.

The European aurochs depicted in Paleolithic cave paintings. (Illustrative image).

Unfortunately, the European aurochs also fell victim to human exploitation and mistreatment. As human populations expanded and agriculture developed, the aurochs lost much of its habitat and food sources.

They were also hunted for their meat, hides, and horns, as well as for sport. By the Middle Ages, the population of this animal had significantly declined, and it existed only in isolated wild areas. The last known European aurochs died in Poland in 1627, marking the extinction of the species.

The European aurochs officially became extinct in 1627. (Illustrative image).

However, the story of this wild cattle does not end there. While the wild ancestors of modern cattle have disappeared, their genes still persist in some of their descendants. During the Neolithic Revolution, humans domesticated two subspecies of the European aurochs: one in the Near East that led to taurine cattle (Bos taurus) and one in India that led to zebu cattle (Bos indicus). These domesticated cattle were introduced to various regions around the world, where they interbred with local wild cattle or adapted to different environments. Some modern cattle breeds exhibit characteristics reminiscent of the European aurochs, such as dark coloration and light stripe markings along the back of males, a lighter color in females, or horn shapes similar to those of the aurochs.

Given the ancestral connection of the European aurochs to most modern cattle breeds, its revival through selective breeding or backward breeding is feasible. Initial efforts were made by Heinz and Lutz Heck using modern breeds to create the Heck cattle breed. While introduced into nature reserves across Europe, Heck cattle exhibit significantly different physical characteristics from the European aurochs. Current efforts aim to produce an animal closely resembling the aurochs in morphology, behavior, and genetics.

The genes of the European aurochs still exist in some of their descendants. (Illustrative image).

In recent years, scientists have been attempting to save the European aurochs from extinction using modern technology and selective breeding. Two leading projects in this effort are the Tauros Program in the Netherlands and the Auerrind Project in Germany. Both projects share research and breeding activities and aim to recreate an animal resembling the European aurochs in size, appearance, behavior, and DNA.

These projects utilize historical records, archaeological evidence, genetic analysis, and artistic representations as guides for their breeding goals. They also employ modern breeds that carry a significant portion of the European aurochs’ DNA, such as the Chillingham white cattle in northern England, the Spanish fighting bull in the Iberian Peninsula, and the Chianina cattle in Tuscany.

Efforts to revive the European aurochs have made significant progress since their inception over a decade ago. They have produced multiple generations of animals increasingly resembling the original European aurochs. Some of these animals have been released into nature reserves or rewilding areas across Europe, where they can contribute to ecosystem restoration and biodiversity conservation. The projects hope to achieve the ultimate goal of creating an animal that is genetically indistinguishable from the extinct aurochs within this century.

Scientists are working to bring back the European aurochs. (Illustrative image).

The revival of the European aurochs is not just a scientific achievement but also a cultural and ethical one. It is an effort to rectify some of the damage that humans have inflicted on nature and to restore some of the lost beauty and diversity of life on Earth. By bringing the European aurochs back from extinction, we are also reclaiming a part of our history and heritage.