-

Construction Period: 1446 – 1515

-

Location: Cambridge, England

Part of the worldwide fame of King’s College Chapel in Cambridge comes from its choir and the annual Christmas carol service broadcast around the globe. However, the primary reason thousands of visitors come to the Chapel each year is to admire an architectural marvel. This is a prominent example of English Perpendicular architecture, a special Gothic style that later manifested itself most majestically through the fan-vaulted ceiling, a unique structural form in English architecture of this period. The architecture creates large areas for stained glass, as is the case with the magnificent stained glass windows found throughout Europe. Ultimately, the Chapel houses an immense amount of interior woodwork, screens, and altars, described by Nikolaus Pevsner as “the quintessential work of Renaissance style in England”.

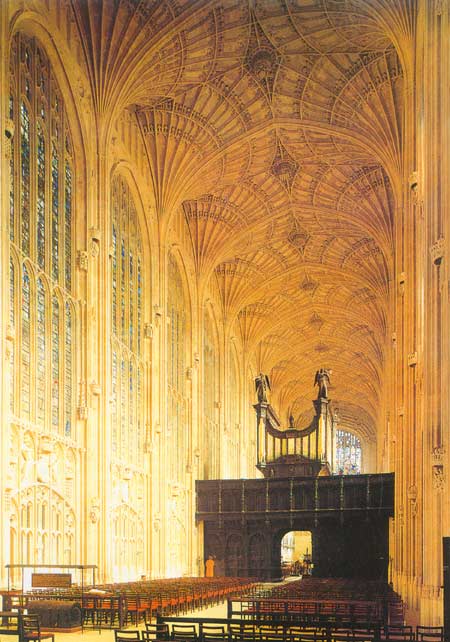

View facing East from the central nave of the Chapel towards the choir,

showing the fan-vaulted ceiling and the wooden screen in the center.

History

Henry VI (1421 – 1471) founded St Nicholas College (his patron saint) in 1441, and in 1443 it was renamed “The Royal Foundation of Our Lady and St Nicholas.” The building served as the school (now the old school within the university) and formed a courtyard located to the north of the current Chapel. According to Henry’s will in 1488, a much larger design was envisioned, with a grand courtyard situated to the south of the Chapel, the dimensions of which he specified precisely. He also suggested that the building’s features should be more restrained rather than ostentatious. It was not until the 19th century that the university was completed in three phases – the eastern end was completed by William Wilkins, featuring a famous translucent screen that emulated the Chapel to create a striking impression.

Thus, the Chapel forms part of a courtyard, similar to chapels at Oxford. As a chapel rather than a church, and recognized as the King’s Chapel, akin to the original Perpendicular St Stephen’s Chapel at Westminster, the layout of the King’s Chapel is a tall rectangular box, although larger and spatially simpler than any chapel before or after it in England. The side chapels taper inward, held back by buttresses on either side, thereby not affecting the main space.

View from outside the Chapel from the Southwest, showcasing the architectural context of the Chapel.

Three Construction Phases can be deduced: Phase 1 from 1446 to 1461, under the direction of master mason Reginald Ely, concluded when Henry VI was deposed. Only minor construction occurred over about 15 years before Phase 2 commenced from 1476 to 1485, finishing during the reign of Richard III. Phase 3 began in 1508, the last year of Henry VII’s reign, and continued until 1515. The fan-vaulted ceiling construction began in 1512, with most of the intricate carvings executed by Thomas Stockton during this phase, under the reign of Henry VIII – featuring the rose on the crown, the iron grid, and the lily symbolizing the king’s patronage. As noted by Francis Woodman, what began as “a pious act and profound religious awareness” was regarded as achieving perfection as “a splendid artistic object and propaganda for the dynasty,” contrary to the founder’s call for restraint.

Key Facts:

-

Length: 88m

-

Width: 12.7m

-

Height: 24.4m

-

Windows: Completed over 25 years

The Massive Fan-Vaulted Ceiling

The wooden ceiling of the Chapel is one of the most beautiful and largest wooden ceilings from the late medieval period in England. The magnificent fan-vaulted ceiling was constructed during Phase 3.

|

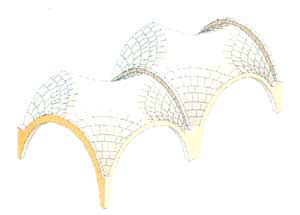

| Diagram of the two-compartment fan-vaulted ceiling, viewed from above. This special vaulted ceiling shape is very complex and is unique to English architecture of this period. |

The ribbed components, completed in Phase 1, suggest another form of vaulted ceiling (lierne), possibly a unique intention of Reginald Ely. As a result, after 1508 the “diagonal” ribs from the buttresses branched out into five ribs of each quarter of the fan-vault. There is still debate regarding the designer of the fan-vaulted ceiling, although it is generally believed to be John Wastell, master mason from 1508, along with John a Lee, Henry Smith, William Vertue, and Henry Redman, all of whom were royal masons, involved in the university at various construction stages.

There are numerous examples of fan-vaulted ceilings in England, often spanning relatively small chapels connected to earlier churches. However, at Sherborne Abbey, redesigned from 1475, the space between the chapel and the transept is 7.9m wide, with other buildings having spans of 8m or more: Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster, Bath Abbey, the so-called New Work at Peterborough Cathedral, and the King’s College Chapel, which has a span of up to 12.7m.

As with later Gothic works, decorative ribs were applied to the surface of the fan-vaulted ceiling, but the thin shell of the fan vault differs fundamentally from other surfaces. For instance, pointed arches consist of four parts curving in only one direction, and structural characteristics can only be calculated by studying a typical cross-section. The fan-vaulted ceiling curves in two directions, meaning that the structural analysis of the ceiling, as well as that of a dome, is much more complex. Professor Jacques Heyman utilized thin shell theory to demonstrate the structural impact of the shape. In initial estimations, the horizontal forces in each compartment of the King’s Chapel are approximately 16 tons. However, the hollow conical section of each fan vault is partially filled with rubble, to stabilize the vault, reducing horizontal thrust at each buttress by about 10 tons.

John Wastell also designed the intersecting ribbed vault at Canterbury Cathedral. His style is recognizable by a certain clarity: the fan-vaulted ceiling at Westminster, built almost concurrently, is richly intricate but visually overwhelming. The fan-vaulted ceiling of Wastell at King’s Chapel is effective in both structure and form, easily understood by dividing the ribs in each compartment. The quality of workmanship must also be very high – “certainly this is the most meticulously designed, accurately carved, and high-quality vaulted ceiling in England”, and this standard continued in Stockton’s decorative carvings on the walls: roses, ironwork, and crowns that are almost entirely sculpted.

Stained Glass

|

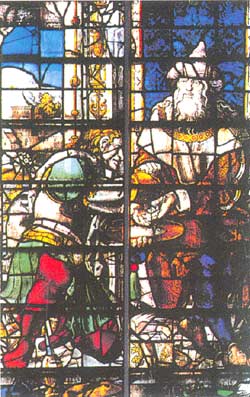

| Detail of the East window, depicting Pontius Pilate washing his hands. The stained glass at King’s College Chapel is among the most beautiful in Europe. |

The stained glass at King’s College Chapel is the most complete set of church windows preserved from the time of Henry VIII, and even the contracts for the design and construction in this style still exist. Barnard Flower seems to have subcontracted some stages to six other glass painters, but there is some debate regarding the overall design responsibility for the window. Whoever it was, whether it was the Dutchman Adrrian van den Houte or Dierick (most likely designed by this individual) – they were certainly familiar with woodcuts and carvings, from which it can be inferred that much of the design is a complex symbolic expression, transitioning from panel to panel, with rich and vibrant imagery. The main theme is the life of Jesus Christ, illustrated with scenes drawn from the life of the Virgin Mary, largely described in geometric symbolism so much so that corresponding patterns are derived from the whale, the passion, and the resurrection of Christ. The architectural details depicted carry elements of the Renaissance rather than Gothic, often alluding to the patronage of the Tudor dynasty, especially in the magnificent East window. At a more abstract level, the color coordination is remarkable; the windows can be evaluated as a pure sample.

Screen

The screen, or “pulpitim”, was installed between 1530 and 1535, featuring an upper section that extends eastward to form the back of the choir area. The construction likely required a large workforce, and while the report on the university chapel does not mention the designer, the style resembles more of the French or Dutch classical schools than the Italian style. Despite its elaborate decoration, it appears to “have a unique style” akin to the structures at Fontainebleau. The repeated round arches divide the architectural ornamentation at the base of the columns, the shaft of the columns, the structure above the capital, and the tightly organized hierarchical system of components that uphold the classical ceremonial significance. Inside, angelic figures, stylized birds, and flora intertwine within the wall columns, the supporting pillars, and the rounded recessed corners between the ceiling and walls.

The intertwined letters HR and AR, along with the arms divided into four parts, represent Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, who reigned as Queen from November 14, 1532, to May 9, 1536, serving as the most concrete evidence of the dating. The elaborate coat of arms is located behind the choir, featuring St. George and a dragon, along with richly detailed figures above and below. In its own way, the screen reaches a level that can be compared to the masterpieces of late Gothic architecture.

In the 1960s, after several discussions, such as the installation of Rubens’ Adoration of the Magi beneath the eastern window and the rearrangement of the chapel’s interior, the chapel now houses a 17th-century Dutch masterpiece that dialogues with the Gothic-style natural stone structure, the unusual stained glass, and the Renaissance wooden screen.