Wang Zhenyi has become a shining star in the field of science, often referred to as the “Marie Curie of China.”

The internationally renowned website Nature featured a female scientist from the Qing Dynasty named Wang Zhenyi in a promotional video for the 2019 “Inspiring and Innovative Scientific Research” awards, highlighting her as a pioneering female scientist of her time.

In the introduction by Nature, Wang Zhenyi is portrayed as a polymath, well-versed in astronomy, mathematics, geography, medicine, and poetry.

In fact, as early as 1994, the Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) named a newly discovered dome on Venus after “Wang Zhenyi.” This illustrates her profound influence in the international scientific community, far exceeding the imagination of ordinary individuals.

Thanks to the third season of the newly aired program “National Treasures” on CCTV, many Chinese people have recently come to know who Wang Zhenyi is.

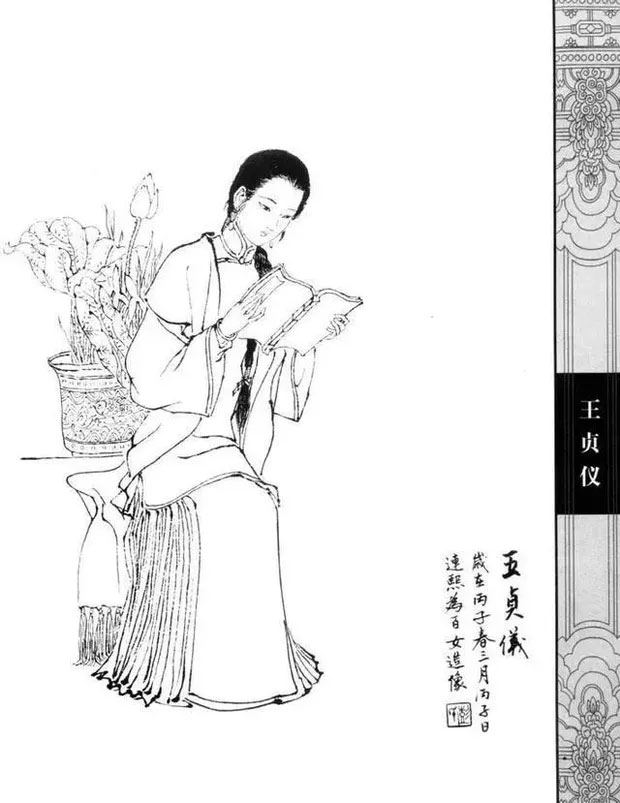

Wang Zhenyi’s portrayal in the program “National Treasures.”

1. Immersed in a Sea of Knowledge from a Young Age

In the 33rd year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1768), Wang Zhenyi was born into a family of scholarly prestige in Jiangsu.

Her grandfather, Wang Jiafu, served as a magistrate with the golden principle: “A clean and honest official, caring for the people as if they were his own children, treating the magistracy as his home.”

Her father, Wang Jishen, was a county official who, after several failures in the imperial examinations, turned to study medicine and became a well-known doctor.

Growing up in a family with a strong educational background, Wang Zhenyi was fortunate to receive an excellent education from a young age. However, during the ancient feudal society in China, such an educational environment alone was not sufficient to create an extraordinary female scientist. Without her later experiences, Wang Zhenyi might have become a delicate lady like Lin Daiyu in “Dream of the Red Chamber.”

Wang Zhenyi’s image in a 1996 work by contemporary Chinese artist, Peng Lianxi.

In 1779, Wang Jiafu passed away in the Northeast after being exiled to Jilin for blasphemy, leaving behind a treasure trove of knowledge comprising 75 large bookshelves for Wang Zhenyi, who was only 11 years old at the time.

Not only did this collection include rich literary works, but also books by ancient scientific masters such as Zu Chongzhi, Zeng Yi Xing, and Guo Shoujing (a Chinese astronomer, irrigation engineer, mathematician, and politician during the Yuan Dynasty). Among them, the works of Zu Chongzhi are particularly valuable as he was a renowned scientist during the Southern and Northern Dynasties in Chinese history and the first person in the world to accurately calculate the value of pi to seven decimal places, along with many other outstanding scientific inventions.

This is closely related to Wang Jiafu’s own research interests. He achieved certain accomplishments in calendar calculations and mathematics, even participating in the compilation and editing of the mathematical book “Mai Shi Tong Sheng” by Mai Wending (a prominent mathematical family during the Qing Dynasty). Furthermore, Wang Zhenyi’s father later “turned from literature to medicine.” It is evident that the Wang family had a strong inclination towards scientific and academic research.

Under the guidance of her grandfather and father, Wang Zhenyi did not disappoint them. With the vast collection of books left by her grandfather, she immersed herself day and night in a sea of knowledge. She even wrote the phrase “In life, what is there to be poor in learning, when holding knowledge is a precious treasure” to encourage herself.

Therefore, to achieve success, one needs not only the support of the family environment but also personal effort.

2. Traveling and Reflecting, Breaking the Mold of Traditional Female Thinking

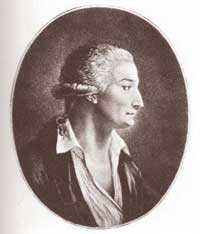

At the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, the astronomer, mathematician, and calendar expert Mai Wending was immensely famous. “Mai Shi Tong Sheng” is a compilation of the academic achievements of his research summarized by later generations.

Mai Wending, mathematician of the Qing Dynasty.

Five years after her grandfather’s death, Wang Zhenyi nearly read the entire treasure trove of books he left behind. At the age of 16, she returned to her hometown in Jiangsu with her parents and then traveled with her father and grandmother to practice medicine everywhere.

From the Northeast to Jiangsu, then from Nanjing to Beijing, and later to Shaanxi, Hunan, and even the eastern part of Guangdong. Over more than two years, she traveled extensively, covering a distance too vast to count.

Half of her life serves as a perfect testament to the ancient proverb: “Read ten thousand books, travel ten thousand miles.”

Experiencing the complexities of human relationships, customs, and cultural nuances in various regions helped Wang Zhenyi completely break away from the limitations of thinking typical of ordinary women.

She courageously wrote lines such as “Traveling a thousand miles and reading ten thousand volumes, my heart is stronger than any husband,” and “Who says women are not heroes?”

It can be said that Wang Zhenyi is one of the earliest representatives advocating for women’s equality during the Qing Dynasty.

3. Embracing Western Knowledge, Excelling in Mathematics and Astronomy

Wang Zhenyi in a 2018 calendar themed around foreign women.

After “reading a hundred thousand books and traveling ten thousand miles,” Wang Zhenyi, now 18 years old, returned to Nanjing to establish her career.

It should be noted that an 18-year-old girl in the old days was often pressured by her family regarding marriage. Although there are no records left, it is not hard to guess that Wang Zhenyi’s family did not place excessive pressure on her in this regard. If there was any, based on her knowledge and character, she would not have been easily subdued and would have fought to the end.

Do not forget that Wang Zhenyi spent five years in Jilin, studying her grandfather’s books while also learning horseback riding and martial arts from a local Mongolian woman in the army. She even reached the level of “riding and shooting, galloping like the wind.”

Thus, upon returning to Nanjing, she began to freely research and explore her own scientific interests.

Her journey started with mathematics, which her grandfather had taught her from a young age. From the 13 volumes of “De Feng Ding Suo Ji” that Wang Zhenyi left behind, we can see that her research related to trigonometric functions and the Pythagorean theorem.

“The Solution to the Pythagorean Triangle” occupies a significant portion of her research, detailing the trigonometric formulas derived from the West that were not fully understood at the time. These studies were of great importance for the development of arithmetic in China.

Wang Zhenyi deeply understood this, so she not only strived to explain “Western learning” but also simplified and edited “Mai Shi Mathematics” by Mai Wending, a work her grandfather highly valued.

She compiled “Calendar Calculation” into “Simplified Calendar Calculation” and adjusted “Original Calculation” (arithmetic calculated using sticks) by Mai Wending into “Interpretation of Calculation.” Unfortunately, these two works, totaling seven volumes, have been lost.

Only the volume “De Feng Ding Suo Ji” remains, in which she complained about the complex and convoluted presentation of arithmetic in Mai Wending’s book and clearly stated her purpose in editing his research was to simplify it for future generations to learn.

Interestingly, in Mai Wending’s book “Calendar Calculation”, astronomical phenomena such as solar and lunar eclipses are mentioned. So, how can a mathematician extend their understanding to astronomy?

In fact, almost all mathematics in ancient China was applied mathematics. Therefore, ancient mathematics was closely related to lunar calendar calculations, astronomical observations, and even the production of musical instruments.

As a result, mathematicians were often also academic researchers and could even be astronomers. Wang Zhenyi, a woman passionate about research and exploration, was no exception. She studied both mathematics and explored astronomy.

In the field of astronomy, Wang Zhenyi left behind works such as “Explanation of Axial Precession” (which refers to the slow and continuous variation of the orientation of an astronomical body’s axis of rotation), “Differentiating the Ecliptic and the Equator” and “On the Sphericity of the Earth.”

For ancient people, the concept of “precession of the equinoxes” meant that the position of the same star changes slightly on the same day each year. After decades of accumulation, this change would have a significant impact on climate and timekeeping.

What Wang Zhenyi accomplished was synthesizing the theories of Nüxi, Zuo Chongzhi, Zhang Yihang, Guo Shoujing, and other predecessors, while combining Chinese and Western calendars, ultimately arriving at a more accurate conclusion that “every 70 years, the winter solstice shifts back by 1 degree.”

A postcard depicting the image of Wang Zhenyi.

More importantly, Wang Zhenyi confirmed the validity of the “spherical Earth” theory through various “earth experiments”, while the theory of “a round sky and a square Earth” was still prevalent at that time. This was a very advanced scientific understanding by the mid-Qing Dynasty.

For this reason, in her subsequent research, Wang Zhenyi accurately explained the positional relationship of the sun, Earth, and moon during solar and lunar eclipses, along with the causes of these astronomical phenomena. She later wrote the “Explanation of Lunar Eclipses” for future generations to learn from.

It should be noted that the Chinese folk belief at that time was that “the celestial hound eating the moon is an ominous sign.” This indicates that Wang Zhenyi’s thoughts and research outcomes transcended the limits of time and space.

In this context, Wang Zhenyi’s research achievements spread to the distant Western lands through missionaries. As a result, she became a shining star in the field of science, often referred to as the “Marie Curie of China.”

Unfortunately, Wang Zhenyi passed away from a sudden illness at the age of 29. A large number of her scientific research manuscripts were also lost thereafter, with only a very small portion remaining, but it is enough to showcase her greatness.

Looking back at Wang Zhenyi’s life, many might argue that she did not achieve any groundbreaking scientific research results. However, we must also consider that due to the limited circumstances of her era, Wang Zhenyi, a woman in feudal times, produced numerous research outcomes by the age of 29, sufficient to demonstrate her extraordinary capabilities.

The spirit of Wang Zhenyi provides us with a model of infinite hope for future generations. Regardless of her status as a Qing dynasty individual, a woman, or a Chinese person, she left behind a phrase as a testament to the spirit of equality and the desire for research that transcends gender:

“We are all human, with the same heart.”