After a sharp iron rod pierced the head of a worker in the United States, he drove himself home and lived for another 12 years.

Can a person with a rod through their head go home by themselves?

Phineas Gage was a railroad worker in Vermont, USA. His daily task involved clearing rocks to lay down tracks. If a rock was too large to move by hand, Gage would drill a hole and pack it with explosives to break the rock, according to BBC.

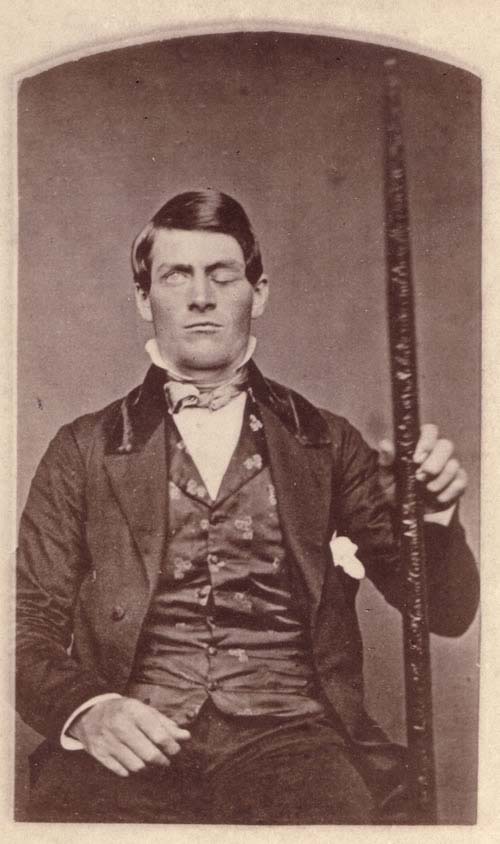

A portrait of Phineas Gage painted after the iron rod pierced his head. He is holding the rod that caused the accident. (Photo: Wikipedia.)

However, on September 13, 1848, an incident occurred when Gage packed explosives into a hole in a rock near the town of Cavendish, Vermont. Gage’s iron rod accidentally fell onto the rock’s surface, creating a spark that ignited the explosives. The explosion propelled the iron rod—approximately one meter long, 3 cm in diameter, and weighing 6 kg—straight through the head of the 25-year-old. It pierced from below his left eye to the top of his skull, landing 30 meters away from the rock.

According to the Huffington Post, John Harlow, the doctor present at the scene, recounted that the rod, approximately one meter long, 3 cm in diameter, and weighing 6 kg, “was covered in blood and brain.” It penetrated the skull, traversed the left cerebral lobes, destroyed a significant portion of the brain, and pushed Gage’s eyeball out of its socket. To the astonishment of all witnesses, the foreman remained conscious and quickly stood up to walk around. He even claimed he would return to work on the rocks in two days.

Back at the hotel, Gage lay down for Harlow to treat his wounds. The doctor shaved his scalp and stopped the bleeding. He removed small bone fragments, repositioned larger bones displaced by the rod, and bandaged Gage’s head with adhesive tape. By 11 PM, the young man had stopped bleeding and went to sleep.

The next morning, Harlow allowed family members to visit Gage. The patient recognized his mother and uncle, which was a good sign. However, a few days later, Gage fell into a semi-comatose state due to a brain infection. Fearing the worst, his family prepared a coffin. Harlow immediately performed surgery on Gage to drain pus from the wound through his nose. After a few weeks, the patient’s condition stabilized, although he had completely lost vision in his left eye. By January 1849, the man had fully recovered. Reflecting on Gage’s care, Harlow humbly remarked, “God healed him.”

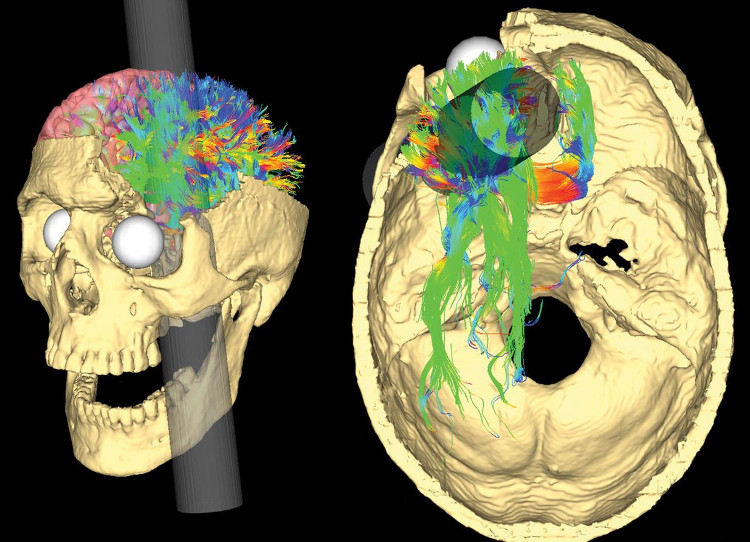

Illustration of Gage’s injury. (Photo: Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, et al).

Despite this, Gage’s personality changed. Dr. Harlow described the “mental state” of the 25-year-old as follows: “The bosses who once regarded Gage as the most efficient foreman noticed a change in his mind and refused to hire him again. The patient became erratic, rude, vulgar, impatient, indecisive, making a series of plans only to abandon them immediately upon seeing a more feasible alternative. The balance between his intellect and animal instincts seemed to have been destroyed. His mind changed to the point that friends and acquaintances remarked that Gage was no longer Gage.” Some reports assert that the foreman permanently lost his ability to control himself, behaved inappropriately in many social situations, exhibited violence, and “could not be controlled” to the extent of harassing children.

In contrast to this view, psychologist Malcolm Macmillan from Deakin University (Australia) believes that Gage’s behavioral changes actually lasted only a short time. “This case is worth remembering because it illustrates how a small story can be woven into a scientific mystery,” he wrote in his book An Odd Kind of Fame. This argument was heavily criticized. Prior to Macmillan, Dr. Henry Bigelow from Harvard University also claimed that Gage “had recovered both physically and mentally.” He concluded that the patient’s brain was entirely normal because he could still walk, talk, see, and hear. Later, it was discovered that the tests Bigelow conducted on Gage focused solely on sensory and motor functions, which were not convincing enough.

Overall, experts find it very difficult to confirm whether Gage’s personality changed because very few people knew him well enough to be certain about the character of the man before the accident. On the other hand, the story is likely complicated by the limited knowledge of brain injuries at the time.

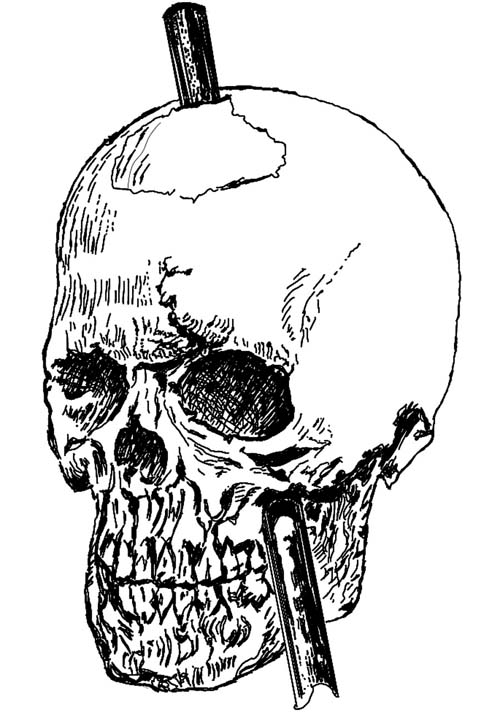

The rod pierced from below Gage’s left eye to the top of his skull. (Photo: BBC.)

For the scientific community of that time, Gage’s accident was the first evidence that brain damage could affect human behavior and personality. However, even today, neuroscientists have yet to satisfactorily explain why Gage did not die immediately after the iron rod penetrated his skull.

Gage’s health rapidly deteriorated in 1859. He moved to San Francisco to live with his mother, brother-in-law, and sister. Later, he developed epilepsy and died in 1860.

Seven years later, his body was exhumed at the request of Dr. Harlow. Today, both his skull and the iron rod are displayed in the Harvard Medical School in the USA. His name appears in many college textbooks and scientific journals.

Subsequent doctors also studied the case of Phineas Gage’s death and concluded that the accident, although it did not cause much physical harm, led to significant psychological trauma.

They recognized that the left frontal lobe of Gage’s brain was the only area affected by the injury. Therefore, they realized that this was the region responsible for controlling personality and impulses.

This discovery also led researchers to another interesting conclusion: the brain has the ability to heal itself. Although the new personality traits emerged almost simultaneously with his recovery, over time, he began to revert to his old human trajectory. However, later scientists suggested that this was partly due to adaptation to society.

Over time, the case of Phineas Gage has become the most emblematic example supporting the view that social cognition and personality depend on the brain’s frontal lobe. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and neuroscientists believe that much of what is known today about brain function is due to Gage’s injury and the thorough research conducted by doctors of that era.

Even today, the case of Phineas Gage still plays an important role in discussions about brain injury and function.