Data from NASA and ESA reveals a type of giant, extreme planet that possesses the power to rejuvenate its parent star and distort astronomical measurements.

According to a team of scientists led by Dr. Nikoleta Ilic from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in Germany, these are “hot Jupiters” that orbit very close to their parent stars.

Hot Jupiters are a type of exoplanet that has been found frequently in the searches conducted by NASA, ESA (the space agencies of the United States and Europe), and other space agencies, as they are large and relatively easy to observe compared to other types of exoplanets.

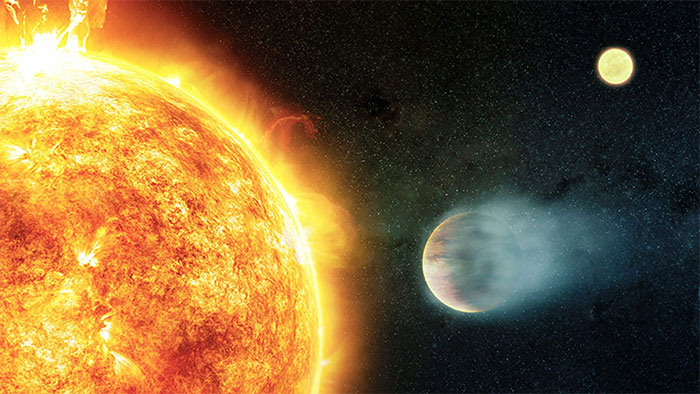

Graphic depicting a binary star system, one of which has a hot Jupiter – (Image: NASA / CXC / M. Weiss)

These are giant gas planets, comparable in size or larger than our Jupiter, but very hot due to their proximity to their parent stars. These worlds are unlikely to support life but are of great interest because they exhibit many unusual characteristics and can influence the formation of other planets in the system.

In a new study, astronomers discovered that some calculations regarding star systems with hot Jupiters may be skewed because the parent star appears “younger” than normal.

“By comparing a star with a nearby planet to a twin star that does not have a planet, we can study the differences in the behavior of stars of the same age,” Sci-News quoted analysis from co-author Katja Poppenhaeger, also from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam.

The researchers examined 10 binary star pairs from data obtained from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and 6 other pairs from ESA’s XMM-Newton Observatory. The results show that in each pair, the star with a hot Jupiter always appears younger than its twin star.

The reason is the extremely strong tidal forces exerted by these hot gas giants, which affect their parent star, causing it to spin faster and become more active, akin to a form of time dilation.

Similar to humans, youthful stars tend to rotate quickly and energetically, slowing down as they age. Therefore, if we apply conventional observational formulas, we may mistakenly conclude that the “parent” of these hot Jupiters is younger than it actually is.

This discovery highlights the necessary changes in astronomical observations that scientists will need to consider in their future studies of planetary systems with hot Jupiters, as well as providing an intriguing piece of evidence for the hypothesis that planets can also influence their parent stars in some mysterious and fascinating ways.