New simulations indicate that a diamond layer nearly 15 km thick could be hidden deep beneath the surface of Mercury, helping to explain some of the planet’s greatest mysteries, including its unusual structure and magnetic field.

Mercury is a planet full of mysteries. For instance, although Mercury’s magnetic field is much weaker than Earth’s, researchers did not expect it to exist at all, as the planet is too small and appears to be geologically inactive. Mercury also has unusually dark surface patches that the Messenger mission identified as graphite, a form of carbon. This characteristic piqued the curiosity of Yanhao Lin, a scientist at the High Pressure Science and Technology Research Center in Beijing and a co-author of the study. The extremely high carbon content of Mercury led him to speculate that there might be something special inside the planet, as reported by Live Science on July 18.

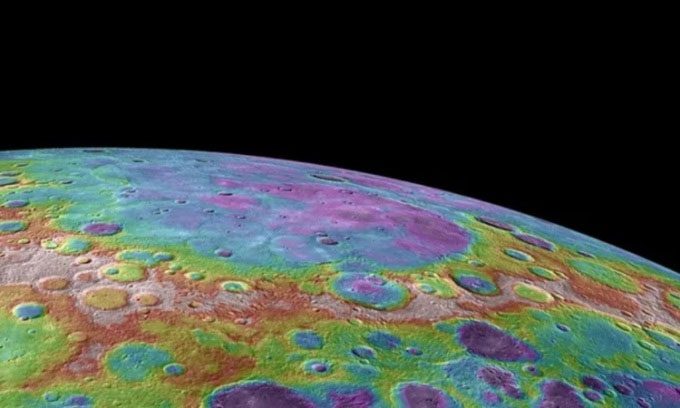

Image of Mercury’s surface. (Photo: NASA).

Scientists suspect that Mercury may have formed similarly to other rocky planets from the gradual cooling of a hot magma ocean. In Mercury’s case, this ocean was likely rich in carbon and silicates. Initially, metals would have crystallized within the ocean, forming a core at the center, while the remaining magma solidified into the mantle and crust of the planet.

For many years, researchers believed that the temperature and pressure of the mantle were only sufficiently high for carbon to form graphite, which would then float to the planet’s surface. However, a study in 2019 suggested that Mercury’s mantle could be over 50 km deeper than previously estimated. This significantly increases the temperature and pressure at the boundary between the core and mantle, creating conditions for carbon to crystallize into diamonds.

To explore this possibility, a research team from Belgium and China, including Lin, examined a chemical mixture comprising iron, silica, and carbon. This mixture resembles the composition of some meteorites, simulating Mercury’s primordial magma ocean. The research team also infused the mixture with varying amounts of iron sulfide, hypothesizing that the magma ocean contained significant sulfur, as Mercury’s surface today is also rich in sulfur.

Using a multi-anvil press, Lin and colleagues subjected the chemical mixture to a pressure of 7 gigapascals, approximately 70,000 times the atmospheric pressure at sea level on Earth, and temperatures reaching up to 1,970 degrees Celsius. Such extreme conditions simulate the environment deep inside Mercury. Additionally, the researchers used computer models to more accurately measure the temperature and pressure at the boundary between Mercury’s mantle and core, while also simulating the physical conditions under which graphite or diamonds would be stable. These computer models will help provide a clearer understanding of the planet’s internal structure.

The experiments indicated that minerals like olivine are likely to form in the mantle. However, the research team also discovered that adding sulfur to the chemical mixture caused it to solidify only at higher temperatures. Such conditions are also more conducive to diamond formation. In fact, the researchers’ computer simulations suggested that under these new conditions, diamonds could crystallize as Mercury’s inner core solidifies. The calculations indicated that diamonds form a layer with an average thickness of about 15 km.

However, mining these diamonds is not feasible. Beyond the planet’s extreme temperatures, the diamonds are located too deep to be excavated, approximately 485 km below the surface. Nonetheless, they are very important for Mercury’s magnetic field. Diamonds could help transmit heat between the core and the mantle, creating a temperature difference that causes liquid iron to circulate, thereby generating the magnetic field, Lin explained.