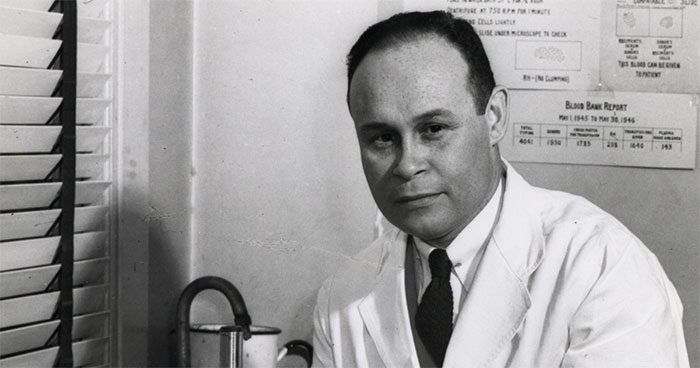

The great invention of Charles Richard Drew directly contributed to saving thousands of lives during World War II and continued to impact the global medical community’s humanitarian efforts thereafter.

As one of the most important surgeons, educators, and innovators of the 20th century, Drew paved the way for the safe storage, processing, and transportation of plasma. His legacy not only saved numerous lives during wartime but also sparked a revolution in plasma storage through blood banking processes.

The Drive to Pursue Medicine

Born in 1904, Drew was the eldest of five children. From a young age, he demonstrated talents in both academics and sports. While in high school, his younger sister tragically passed away from tuberculosis, which inspired Drew to pursue a career in medicine.

In 1922, his athletic prowess earned him a football and track scholarship to attend Amherst College in Massachusetts. Drew was one of only 13 Black students among a total of 600, and on the field, he faced significant prejudice from other teams.

Drew completed his bachelor’s degree at Amherst College in 1926 but lacked the resources to attend medical school. To make ends meet, he took a position as a biology instructor and coach at Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in Baltimore for two years before enrolling at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

Charles Richard Drew was a pioneer in the safe storage, processing, and transportation of plasma.

At McGill, Drew quickly distinguished himself, winning the J. Francis Williams Prize in Medicine and an annual scholarship award in neurosurgery, working on the McGill Medical Journal, and being elected to the medical honor society Alpha Omega Alpha. He earned his medical degree and Master of Surgery in 1933.

Invention That Saved Thousands of Lives

After graduation, Drew began his residency at both the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Montreal General Hospital. It was during this time that he started examining issues related to blood transfusions, also known as intravenous (IV) blood transfusions.

While pursuing his doctorate at Columbia University, where he worked with a physician named John Scudder, Drew continued his research in the field of blood transfusion. Together, they conducted extensive studies on blood preservation and fluid replacement, culminating in the development of an experimental blood bank that operated smoothly for seven months.

Drew’s 1940 doctoral dissertation titled “Blood Reserves: A Study of Blood Preservation” solidified his leading position in this field.

Drew’s breakthroughs in blood preservation were timely.

Drew’s breakthroughs in blood preservation came at a crucial time, as World War II was underway in Europe, and the United Kingdom needed a large supply of blood and plasma to treat injured soldiers. Utilizing the experimental blood bank they had just established, Drew and Scudder spearheaded the “Blood for Britain” program to transport plasma overseas.

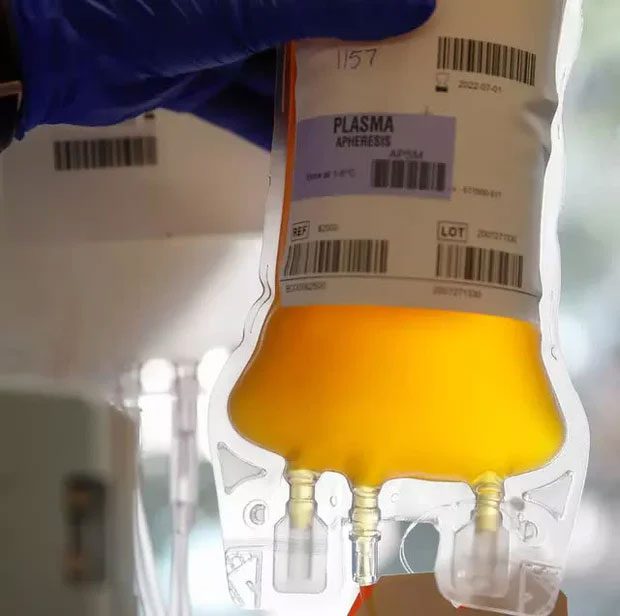

Transporting plasma is a critical requirement in emergencies. Blood contains two main components: red blood cells and plasma. The function of red blood cells is to transport oxygen throughout the body, while plasma carries water along with proteins and electrolytes.

Although plasma does not contain red blood cells, it plays a vital role in helping to replace essential fluids and treat shock—two essential tasks for saving lives. Additionally, plasma itself is easier to store and transport and can be used with any blood type.

Transporting plasma is a critical requirement in emergencies.

Under Drew’s leadership, his team developed new methods for extracting, preserving, and transporting plasma on a large scale, allowing for the shipment of up to 5,000 liters of life-saving plasma to Britain.

A Legacy of Inspiration

Following the success of the “Blood for Britain” program, Drew was appointed assistant director of the blood banking system in the United States, funded by the American Red Cross and the U.S. Research Council.

During this time, he established several mobile blood donation stations, later known as blood transport stations. However, as soon as the United States entered the war, the armed forces implemented a policy that prevented Black individuals from donating blood due to racial discrimination. This misguided decision led Drew to resign from the National Blood Bank in April 1941.

After leaving the National Blood Bank, Drew focused on training and mentoring students at Howard University College of Medicine. According to the National WWII Museum, he often used his own funds to help his students attend conferences and present their research.

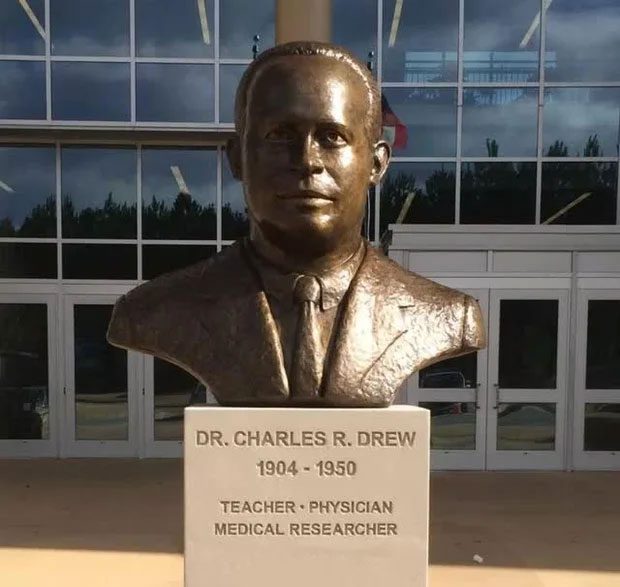

Statue of Charles Richard Drew.

On April 1, 1950, tragedy struck. Drew was involved in a serious car accident while on his way to a clinical conference and died from his injuries. Although his life was cut short, his legacy continues through those he inspired, including his daughter, Charlene Drew Jarvis, a doctor and researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health.