Nearly 200 years before the scientific community recognized the existence of black holes, an English cleric named John Michell published a bold idea about a strange cosmic object. So why didn’t cleric Michell go “viral”?

To this day, the concept of “cosmic black holes” continues to baffle the public, especially considering that the number of black holes could reach billions and is scattered throughout space. For decades in the 20th century, prominent physicists refused to believe in their existence and even dismissed mathematical evidence suggesting that black holes could exist. The list of skeptics even included Albert Einstein, the illustrious physicist who proposed the general theory of relativity, a crucial component for the theoretical viability of black holes.

However, there was one individual who accurately predicted the existence of objects resembling black holes even before Einstein was born. Using only Newton’s laws, the English cleric John Michell predicted the existence of these strange cosmic objects.

Portrait of John Michell.

So who was he, what was his prophecy, and why is John Michell’s name seldom mentioned in history?

Michell was born in 1724 in the village of Eakring, England, as the son of a clergyman named Gilbert Michell and his wife Obedience Gerrard. Although he was educated at home alongside his brother and sister, John Michell quickly demonstrated a keen intellect and strong perception. According to historian Russell McCormmach in the book The Balance of the World: Reverend John Michell of Thornhill, his father Gilbert often quoted a close family friend who described young John as “one of the brightest individuals I have ever met.”

The Michell family adhered to moderate Christianity—a tradition that valued reason over extreme doctrine, originating from the University of Cambridge during Isaac Newton’s time. Thus, when it came time for John to attend university, he chose Cambridge.

John Michell spent 20 years at Cambridge, taking on various roles. After graduating, he taught numerous subjects, including Hebrew, Greek, arithmetic, theology, and geology. In the book The Journal of John Michell, Archibald Geikie recounts that Michell was “passionate about making his own experimental instruments… His room at Queens’ College [Cambridge] was filled with instruments and machinery resembling a workshop.”

It was during this time at Cambridge that Michell began to showcase his “prophetic” abilities, making predictions about scientific advancements.

The statue of Sir Isaac Newton located on the Cambridge University campus. Behind it is a memorial for school members who sacrificed their lives in World War II – (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

In 1750, John Michell published a report on magnetism, where he discovered a new law related to magnets, thereby expanding their application in maritime navigation. In 1760, he published another report on the mechanisms of earthquakes, showcasing methods to locate the epicenter and focusing his research on the catastrophic earthquake in Lisbon in 1755. During this time, John Michell also began analyzing the potential for tsunamis caused by underwater earthquakes. These studies earned him the title of the father of seismology and magnetometry.

After leaving Cambridge in 1764, he married Sarah Williamson and moved to Thornhill in Yorkshire, continuing his father’s pastoral work. When Sarah passed away in 1765, Michell remarried Ann Brecknock in 1773. In addition to his church duties, he maintained correspondence with many contemporary philosophers and intellectuals, including American scientist Benjamin Franklin.

From a 21st-century perspective, the story of a devout Christian with a rich scientific research life may surprise many. However, like most intellectuals of the 18th century, Michell did not distinguish between religion and science. At the same time, the appearance of the telescope in the early 1600s sparked a major philosophical upheaval across Europe.

A painting depicting Galileo Galilei demonstrating his telescope to Leonardo Donato in 1609, painted by the French artist Henry Detouche in the 19th century.

This new device overturned the old conception that Earth and the Universe were eternal creations of God. Telescope permanently changed the way we perceive the world, but for thinkers like Michell, this revolution did not replace God; it simply renewed the mystery of the Almighty: the natural laws being studied remained the laws of God.

In an essay titled Opticks or, A Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colors of Light, written in 1804, Newton stated: “Our duty to [God], as well as to one another, will be evident under the light of Nature“. This was a doctrine John Michell held dear. And as historian McCormmach notes, “his truth about religion was in harmony with the truth of nature.”

Therefore, for Michell, the duty of a clergyman was accompanied by the duty of scientific research. He began to explore cosmology, particularly the nature of gravitational force. This was the field where John Michell made many revolutionary and ahead-of-his-time contributions.

Michell personally constructed a 3-meter-tall telescope, and in 1767, he became the first to apply statistical mathematics to study visible stars. He demonstrated that star clusters, such as the Pleiades, do not appear randomly, but are a result of gravitational attraction.

In 1783, Michell’s friend Henry Cavendish sent him a letter mentioning the difficulties the cleric-scientist was facing while assembling a new telescope device. “If your health allows you to continue, I hope this [referring to the telescope project] will be easier than weighing the world.” Perhaps Cavendish was joking, but his jest was based on real events.

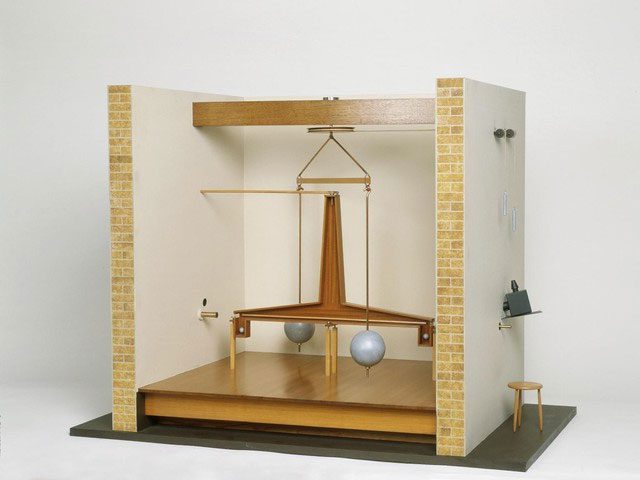

At that time, John Michell was designing a device called a torsion balance, which could help him estimate the density of the Earth through measurements of the gravitational attraction between lead weights. However, John Michell passed away before he could complete the device, and Cavendish utilized the deceased scientist’s torsion balance to conduct measurements in 1797.

Torsion balance model completed by Henry Cavendish – (Photo: Science Museum Group).

Cavendish calculated the Earth’s density with an error of only 1% compared to the results accepted today. It wasn’t until 1895 that another experiment achieved greater accuracy than Cavendish’s findings. Even to this day, variations of the torsion balance proposed by John Michell are still used to measure the gravitational constant, which indicates the strength of gravitational attraction in the Universe.

The Prophecy of Cosmic Black Holes

Also in the year Cavendish sent the aforementioned letter, John Michell published a report containing a strange hypothesis; while its scientific value was not high, it reflected Michell’s observational abilities that surpassed those of contemporary humanity. Using Newton’s laws, Michell’s report explained that the density of a star could be determined by how its gravitational force interacts with nearby celestial objects, such as the orbits of stars or comets.

He then speculated on how light might also possess similar properties:

“Let it be assumed that light particles are attracted in the same manner as all other objects we know… without doubt, since gravity, as we know or have reason to believe, is a universal law of nature“.

The particle theory of light was proposed by Isaac Newton about 80 years earlier, and although no one had proven Newton’s assertion, this view was widely accepted in Michell’s era. Michell explained that theoretically, the behavior of light under the influence of gravity could provide a method for calculating the density of a star, especially if a star is “large enough to significantly affect the speed of the light emitted from it“. Current understanding shows that Michell was incorrect, as gravity does not slow down light, yet his reasoning remains sound.

Also based on this principle, Michell deduced a fact that has now been verified: the gravitational force of massive celestial objects can overpower their own light. He suggested that for this to occur, an object would need a density of matter equivalent to that of the Sun and 500 times larger. According to Michell’s understanding at the time, light could still escape from this object, but then “would be drawn back to the point of origin by the very gravity [of the object].”

Because the amount of light today can never reach us, “we cannot gather information with the naked eye,” yet it can still be detected through the erratic orbits of nearby celestial bodies, altered by the gravitational pull of the invisible star.

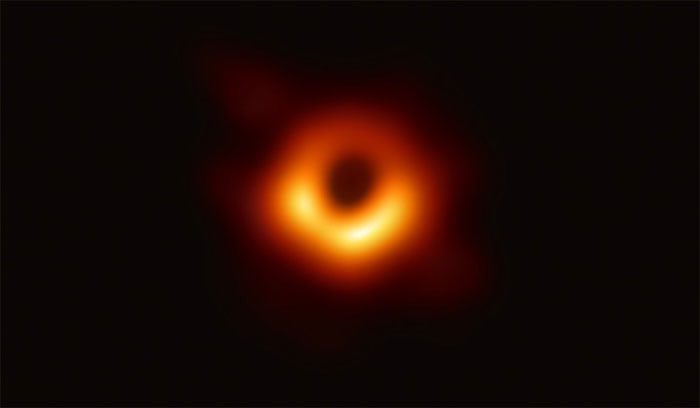

The scientific report by Mr. Michell represents the closest conjectures about the concept of black holes according to Newtonian physics, not to mention the methods to identify them. Modern science has discovered some black holes through measuring the orbits of nearby stars, just as Michell suggested. It wasn’t until 2019 that science captured the first image of a black hole.

The first black hole image in human history, depicting the black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy – (Photo: EVENT HORIZON TELESCOPE COLLABORATION).

According to historian McCormmach, the idea of the existence of invisible stars was proposed multiple times in the scientific community of the time. In the same year that Michell published his scientific report, some astronomers presented fresh insights about dying stars or stars that had never shone.

Not long after these developments, a series of new experiments showed that light is not a particle but a wave, also indicating that light cannot be distorted or held back by gravity. The research of John Michell gradually fell into obscurity until it was rediscovered in the latter half of the 20th century.

In 1994, physicist Kip Thorne published in his book Black Holes and Time Warps, describing the stark contrast between Michell’s and contemporary scientists’ interest in invisible stars and extreme gravity, with the prevailing belief in the 20th century that black holes were not real. In Kip Thorne’s view, Michell’s concept of dark stars and that of other scholars “do not threaten any cherished beliefs about nature” and do not challenge “the permanence and stability of matter“, thus failing to create a breakthrough.

Today, a black hole is defined as “a hole in spacetime, an infinite well from which nothing can escape.” Although this definition differs from John Michell’s understanding, historian McCormmach believes that John Michell would likely embrace this new concept as he was a creative individual, continuing to pursue what he was passionate about.

The Legacy of John Michell – A Man of “Scientific Integrity”

Michell passed away on April 21, 1793, while still serving as the bishop in his beloved Thornhill. The intellectuals of Michell’s time are still renowned today; they published numerous scientific reports and researched widely recognized topics. However, Michell was not the type of person to “chase trends.”

According to McCormmach, John Michell “approached scientific issues in a way that attracted him, in any field, and he pursued them until he chose to stop; he published his work only when and if he was completely satisfied with it“. This somewhat explains his obscurity after his death – he traded fame for intellectual freedom.

As astronomer Ibn al-Haytham stated 700 years before Newton, “those who seek the truth” do not place their trust in established concepts, “but instead doubt their beliefs in them … are those who are passionate about debate and proof.” John Michell adhered to this tradition, and as a self-taught individual like his father, he defended his scientific integrity by distancing himself from popular beliefs.

Michell’s independence of thought allowed him the freedom to pursue another kind of imagination. According to McCormmach, John Michell pursued cosmology because it offered new prospects for his theories. As physicist Albert Einstein remarked in 1929:

“I am artistically enough gifted to utilize my imagination freely. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”