Wood, coal, and even oil extracted from whale blubber were historically used to illuminate lighthouses. The most significant invention in the history of lighthouses is… the Fresnel lens.

|

|

|

|

|

Sandbanks near river mouths are always very dangerous for passing vessels. Therefore, boats equipped with such warning lights were essential. The first of these operated along the coasts of the Netherlands in the 15th century. However, the most famous was a lighthouse ship anchored at the mouth of the River Thames in 1732, followed by a fleet of lightships deployed along the British coastline throughout the 1780s. |

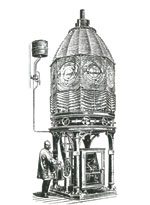

From the early 19th century, converging lenses were created to concentrate the emitted light more effectively. These large lenses featured concentric circular grooves around a smaller central lens. This structure allowed the lens to be lighter while amplifying the light output up to four times compared to traditional reflective mirrors. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Between 1763 and 1777, William Hutchinson, the chief port manager of Liverpool, installed the first lighthouses equipped with parabolic reflective mirrors. These mirrors were designed based on the principles of the French scientist Lavoisier, allowing the light source to be focused on a single point using a concave mirror. By 1780, two French engineers, Teulère and Lenoir, had developed parabolic mirrors made of copper coated with silver. |

In the early 1960s, plastic and fiberglass buoys were manufactured. They were very lightweight. The signal lights on these buoys were powered by solar energy as well as wind energy. By the 1970s, new generation buoys were equipped with compact fluorescent lights. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lighthouses built of wood and illuminated by oil with bent steel reflective mirrors were installed in Sweden between 1669 and 1685. This type of lighthouse had the drawback of always being “sooty” due to the burning oil inside, making the brightness of the signal unclear. |

The idea of using coal as fuel for lighthouse lamps was proposed by the British lighthouse engineer John Smeaton. This simple system produced very effective light signals and lasted into the 19th century. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A lens system weighed up to 5 tons and was designed to rotate on roller bearings. The rotational motion of the lens was controlled by a mechanical clock mechanism. However, the rotation speed of this lighthouse was quite slow. |

The lighthouse installed at Chassiron (France) in 1825 improved the lens design. This was a vertically cylindrical lens, internally equipped with multiple circular prisms to concentrate received light into the center of the circle. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

For lighthouse vessels, a crucial issue is maintaining a fixed light source position while the vessel sways with the tide. In 1915, Dalen, a Swedish engineer, solved this problem by inventing a “oscillating lighthouse.” The lens system was mounted on a balanced oscillating support, ensuring the light source remained stable on the vessel. |

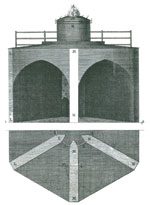

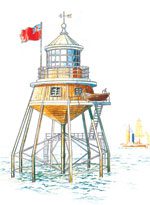

With the widespread use of iron in construction at low installation costs, a lighthouse with nine iron pillars was built in England in 1840, right on a sandbank at the mouth of the River Thames. By the 1850s, over ten such lighthouses had been erected in England and the United States. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the 1960s, the United States designed a modern buoy system that could be controlled remotely, even from a station deep inland. This buoy system, named LANBY, features a floating structure resembling a large circular disc, equipped with a tall tower that emits a strong light signal visible from over 20 nautical miles away. |

A simple, low-maintenance lighthouse was erected near Pembrokeshire (United Kingdom) in 1776. This lighthouse was built on a frame of oak support columns. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The 21st century will witness the emergence of lighthouses with a “robust” yet “elegant” appearance. These lighthouses will be made of steel, concrete, and plastic reinforced with fiberglass. They will operate on solar energy from solar panels and will be fully automated. |

As lighthouses become automated, the final concern is how the technical team can quickly reach them for inspections, maintenance, or emergencies. The 20th century saw the introduction of “hat” lighthouses, equipped with a helicopter landing pad on top. This model was first tested in Sweden in 1970 and has since been implemented in many locations around the world. Since the 17th century, the maritime industry recognized the need for additional lighthouses as maritime trade began to flourish. However, the limitations of the technology and effectiveness of the lighthouses at that time were also apparent. Significant effort was required to maintain them, along with a substantial amount of firewood to keep these light signals operational continuously. Another urgent need was to find feasible methods to control these light sources. From that day, scientific advancements gradually helped modernize these lighthouses, continuing to this day and beyond… Light Sources from the 17th to 19th Century This led to the use of oil. However, this type of fuel had the drawback of producing excessive smoke that blackened the glass of the lighthouse lamps, weakening the emitted light and making maintenance more challenging. Thus, oil lamps only became popular in the 17th century. By the mid-19th century, there was consideration for crude oils or oils refined from plants, such as rapeseed oil, and from animals, particularly oils extracted from whale blubber. However, these fuels were quite expensive. Subsequently, cheaper products that could be locally extracted were used, such as alcohol from waste mash, olive oil, vegetable oil from seeds, and oils derived from fish and whale fat. Generally, the materials used for lighting lighthouses in previous centuries were quite diverse. In terms of construction techniques, wooden lighthouses were built. However, these wooden structures were less resilient to storms compared to their stone counterparts. As larger vessels began to navigate more frequently, the maritime community needed to construct lighthouses on rocky outcrops offshore, not far from the mainland. These lighthouse structures had to withstand harsher weather conditions. An English lighthouse architect, John Smeaton, introduced several innovative ideas that would be applied for years to come. In 1759, John was the first to use a mixture of mortar combined with iron to strengthen the walls of the lighthouses. This was a basic method of creating a material we now call “reinforced concrete.” For the first time since Roman times, humanity utilized “cement” that hardens upon contact with water in the construction of lighthouses. Innovations That Changed Lighthouses At the beginning of the 19th century, long sea voyages began with steam-powered ships that were relatively fast and less reliant on wind and tides. The urgent need at that time was for more powerful lighthouses so that mariners could see them from a great distance. Countries with developed maritime industries began constructing more lighthouses along their coastlines. Concurrently, there was a need to improve the functionality of buoys at sea, ensuring they could be recognized even at night. This demand led to the introduction of floating buoys equipped with bells in the 1860s. A few decades later, self-illuminating buoys emerged, powered by gas containers that allowed the buoy to function for about a month. However, perhaps the most significant innovation of that era was the introduction of the gas lamp. This type of lamp operated on the principle of evaporating the fuel burned inside, typically light oil, by applying appropriate pressure and temperature to the tubular fittings mounted above the burner. Consequently, gas lamps could self-“heat” and emit light six times stronger than previous oil lamps, while consuming significantly less fuel. Later, electric lamps further increased luminosity by tenfold compared to previous generations of lamps. Before World War II, many lighthouses were equipped with a new setup powered by electricity generated from diesel engines. Under this operational principle, lighthouses were fitted with electric lamps along with a reserve gas supply, a signaling system for foggy conditions, and radio transmission equipment. Nguyễn Cao (According to Phares Du Monde Entier) Leave a Reply |