A study led by Dr. Oliver Gutfleisch from Darmstadt University of Technology has discovered micrometer-sized carbon microcrystals in the dust debris of the Chelyabinsk meteorite.

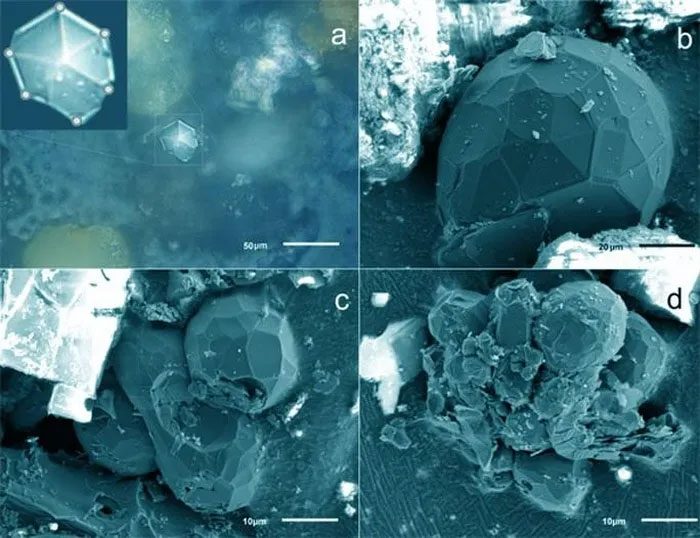

The researchers examined the crystals using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and found that they exhibited many unusual shapes: closed spherical shells and elongated hexagonal prisms resembling sticks. Such carbon crystals have not been seen anywhere on Earth or in any previous extraterrestrial objects.

Carbon is considered the “backbone” of life, so any strange occurrences related to it are of particular interest to planetary scientists.

Strange objects inside the Chelyabinsk meteorite – (Photo: UT Darmstadt)

It remains unclear whether this bizarre material was brought to Earth by the meteorite from an extraterrestrial world, or if it formed during its fall, like a “hybrid” between primordial materials in the meteorite and influences from Earth.

When a cosmic object enters Earth’s atmosphere, its surface is subjected to high pressure and temperature. Air flows tear small droplets from the meteorite, creating a dust cloud, and there is also a possibility that new material forms under those conditions.

The Chelyabinsk meteor, which exploded on February 15, 2013, over snowfields in the Southern Urals, is the largest meteor of the 21st century, with an initial diameter of up to 18 meters.

The Chelyabinsk dust, formed at altitudes between 80 and 27 kilometers, has been detected by several satellites. It moved eastward during its evolution and circled the entire globe in 4 days.

The conditions under which the meteor dust fell can be considered unique: there had been snowfall 8 days prior to the meteor’s fall, creating a distinct boundary that allowed for the identification of the starting point of the dust layer. Approximately 13 days after the meteor’s fall, there was also a snowfall that preserved the meteor dust that had fallen at that time.

The Chelyabinsk incident shows that Earth is not completely shielded from dangerous space objects, while also providing our planet with unique materials synthesized under conditions that cannot be replicated in advanced laboratories.

The research findings were recently published in the journal EPJ Plus.