Scientist Chien-Shiung Wu is often referred to as the “First Lady of Physics.” She made significant contributions to the research of the atomic bomb, despite facing gender discrimination in society at the time.

Chien-Shiung Wu was a Chinese-American scientist whose scientific career has left an immense legacy for humanity, particularly in the field of nuclear physics.

She played a crucial role in the development of the atomic bomb for the United States during World War II.

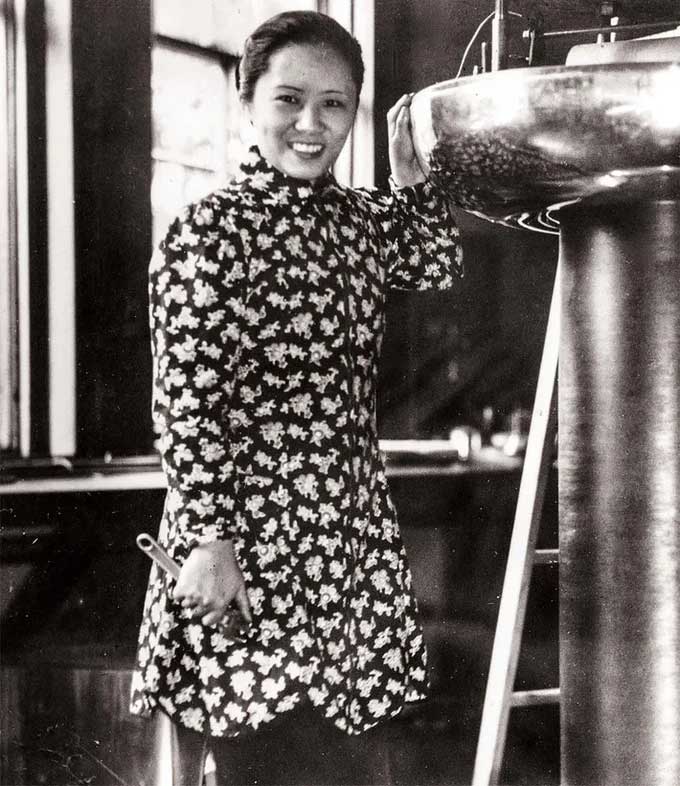

Chien-Shiung Wu assembling an electrostatic generator in the physics laboratory at Smith College in 1942 (Photo: National Geographic).

A Top-Secret Project

In 1939, World War II began to escalate, but it wasn’t until the attack on Pearl Harbor in Oahu, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, that the United States officially entered the fight against fascism.

Prior to this, the country had developed a top-secret plan to create an atomic bomb known as the “Manhattan Project.”

Italian physicist Enrico Fermi was the first to suggest using nuclear fusion to create a super bomb as part of this project.

Chien-Shiung Wu attracted Fermi’s attention with her doctoral thesis on nuclear fission, and they decided to invite her to join the project.

There, Wu developed the process for separating uranium atoms into charged uranium-235 and uranium-238 isotopes through gas diffusion.

This led to uranium enrichment, an essential component in nuclear reactions.

Alex Wellerstein, a historian and professor at Stevens Institute of Technology, stated: “As a member of the team, Chien-Shiung Wu continuously explored and designed radiation detectors, making significant contributions to the research on gas diffusion for uranium enrichment, a method that remains effective to this day.”

He explained: “Gas diffusion was absolutely essential and played a vital role in the atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. on Hiroshima (Japan) during World War II. Later, this technology enriched the United States during the Cold War.”

According to him, this discovery was so valuable and important that details about it were classified as national defense secrets due to its connection to the technology for building nuclear bombs in the U.S.

Breakthroughs in Physics

After World War II, she focused on researching the process of radioactive decay.

In the mid-1950s, Wu conducted a famous experiment to test the conservation of parity law.

At that time, this principle was widely accepted in science but lacked practical proof.

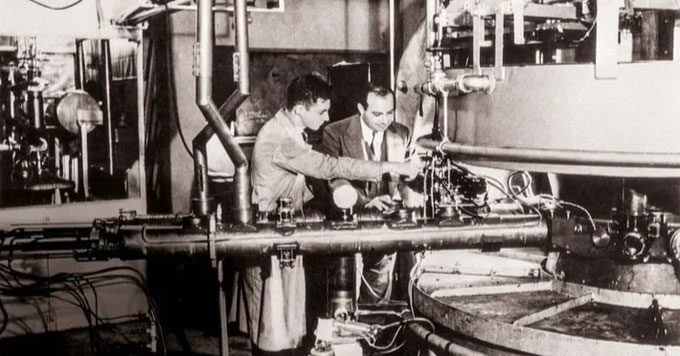

Colleagues of Chien-Shiung Wu working with her in the laboratory. (Photo: National Geographic).

She collaborated with two other scientists, Tsung-Dao Lee from Columbia University and Chen-Ning Yang from the University of California.

The two physicists suspected that a newly discovered particle called the kaon violated the theories of parity conservation.

According to the parity conservation law, decaying atoms should emit electron particles symmetrically.

It was Chien-Shiung Wu who proposed testing this law based on the radioactive isotope cobalt-60.

After sleeping only four hours a night, she worked tirelessly with her colleagues to develop this ambitious experiment.

The scientist cooled cobalt crystals to temperatures near absolute zero, then used a powerful magnet to align their cores and observed whether the decay emitted electron particles symmetrically.

After months of experimentation, Chien-Shiung Wu concluded that the cobalt nuclei emitted electrons on one side but not the other, thereby proving the parity conservation law at that time to be completely incorrect.

This significant breakthrough helped the research team win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1957, but the Nobel Committee did not recognize her substantial contributions.

Alongside her famous research on parity conservation, Wu also conducted a series of important experiments in nuclear and quantum physics.

In 1949, she confirmed the beta decay theory of physicist Enrico Fermi and corrected inconsistencies between the theory and inaccurate results from previous experiments.

She also developed a universal version of this theory.

Overcoming Gender Barriers to Pursue Passion

Chien-Shiung Wu was born in 1912 in Lixiahe, Jiangsu Province, about 65 kilometers from Shanghai.

Although it was uncommon for girls to receive an education in China at that time, Wu attended elementary school at a girls’ school founded by her father.

In 1930, she enrolled in a Mathematics program at National Central University in Nanjing.

However, the revolutionary advancements in modern physics at the end of the 19th century, such as the discovery of atomic structure and X-rays, sparked her passion for science as a young student.

As a result, she decided to switch her major to physics and graduated at the top of her class in 1934.

Encouraged by her academic advisor and supported financially by her uncle, she moved to the United States in 1936 to pursue her Ph.D.

Initially, Chien-Shiung Wu planned to study at the University of Michigan, but at that time, the U.S. faced gender discrimination, especially in the male-dominated field of physics, where women’s Ph.D. applications were largely dismissed.

She then decided to go to San Francisco, where she met physicist Luke Chia-Liu Yuan, who later became her husband.

Yuan took her on a tour of the radiation research laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

Scientists there had just invented a cyclotron, a particle accelerator that increased the speed of charged particles.

Fascinated by nuclear research conducted at this laboratory, Chien-Shiung Wu successfully enrolled in the Ph.D. program in physics at Berkeley.

During her studies, she closely collaborated with nuclear expert Ernest Lawrence, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939, and scientist Emililo Segrè.

At Berkeley, Chien-Shiung Wu not only stood out and drew attention from her male colleagues due to her gender and ethnicity but also for her keen intellect and profound knowledge in scientific research.

Historian Sharon Bertsch McGrayne noted: “She was the beauty at Berkeley.”

In his memoir, nuclear physicist Ernest Lawrence wrote: “When Wu walked across campus, she looked like a queen, and it was no surprise that a crowd of boys admired her.”

At Berkeley, she researched the electromagnetic radiation produced during the deceleration of charged particles, as well as the radioactive isotopes of xenon.

These were created by the nuclear fission of uranium atoms.

In June 1940, she successfully obtained her Ph.D. with honors, but the school did not retain her for employment.

After a brief period of postdoctoral research, Wu moved to the East Coast of the United States and became a faculty member at Smith College.

Shortly thereafter, the war broke out, providing her the opportunity to participate in top-secret military projects, where she made significant contributions, particularly in the development of the atomic bomb.