The Eye of the Storm: A Mysterious Feature on Jupiter

Jupiter is home to an incredibly harsh climate, characterized by numerous storms. The most famous of these is known as the Great Red Spot, which scientists believe is so powerful that it could swallow the Earth whole. This massive storm has been observed from Earth since 1830.

Jupiter is the largest planet in the Solar System, but at a distance of 778 million km from the Sun, it takes nearly 12 Earth years to complete one orbit.

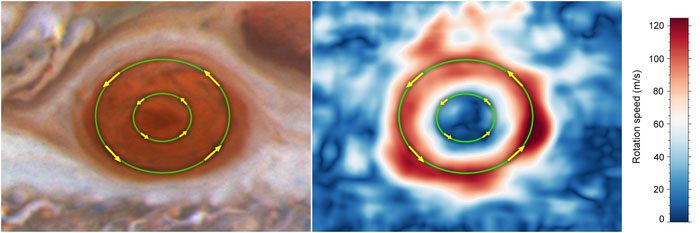

The Great Red Spot is an enormous storm located in Jupiter’s troposphere (0-50 km) that has existed for over 350 years. Its outer winds reach astonishing speeds of 270-425 mph (430-680 km/h), while its peripheral winds are slightly lower, at just under 270 mph (430 km/h). The inner region (the eye of the storm) is quite the opposite, being relatively calm and stable, devoid of clouds and strong airflow.

The Great Red Spot is even larger than our planet and has captured the attention of astronomers who have been observing it for over 150 years.

However, whether life exists in this calm area of the storm is not directly related to the storm’s dynamics. The environment there may be quiet, but it could also be unsuitable for life to thrive.

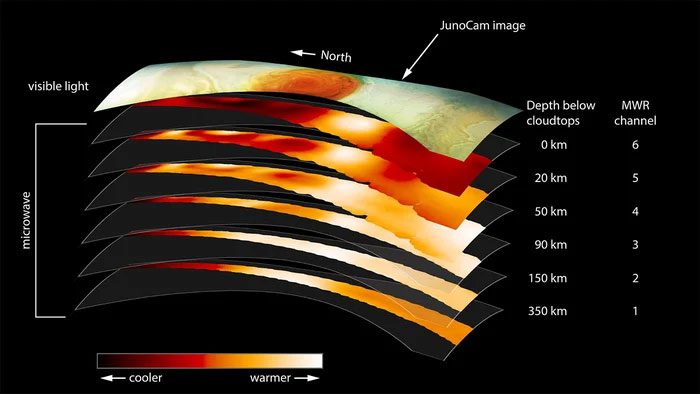

Currently, we know that Jupiter’s atmosphere can be divided into four layers: the troposphere, stratosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere. However, Jupiter does not have a solid surface, so its troposphere and the liquid interior transition similarly to our planet. Thus, its atmosphere primarily consists of hydrogen and helium, with only a small fraction of other compounds, including methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and water.

Jupiter’s storms typically occur in the troposphere and stratosphere of its atmosphere.

The troposphere of Jupiter is where temperature decreases with altitude, allowing for the presence of various types of clouds, including ammonia, water, and hydrogen sulfide. Jupiter’s storms may be triggered by the thin layer beneath the water clouds, where lightning has been observed. According to various data sources, the thickness and temperature range of Jupiter’s troposphere vary significantly. It is currently accepted that the troposphere of this planet extends about 50 km above the visible cloud layer (or at a pressure level of 1 bar).

In this layer, the temperature ranges from around 110K (-163 degrees Celsius) to about 340K (67 degrees Celsius). The troposphere of Jupiter primarily consists of hydrogen and helium, along with trace amounts of water, ammonia, ammonium sulfide, and other substances.

These materials create clouds with varying colors and densities at different altitudes. The white crystalline bands in the highest clouds are called zones, while the reddish-brown bands of ammonium sulfide in the lowest clouds are referred to as belts.

Of course, the thickness and temperature range of Jupiter’s stratosphere also vary among different datasets. Generally, the stratosphere extends about 200 km above the troposphere (pressure levels from 0.1 bar to 0.00001 bar). Consequently, the temperature decreases from around 340K (67 degrees Celsius) to about 110K (-163 degrees Celsius).

The stratosphere of Jupiter primarily consists of hydrogen and helium, along with trace amounts of methane, ethane, acetylene, and other gases, forming thin, transparent clouds at various altitudes.

The highest clouds are made of ice crystals, forming auroral rings near the poles. Additionally, there are significant and complex wind speed changes in Jupiter’s stratosphere, leading to various swirling structures and storm phenomena.

Scientists have traced one of these molecules—hydrogen cyanide—present in strong wind currents near the poles, with speeds around 400 meters per second. These winds correspond to 1,450 km/h, which is more than three times the wind speed measured in the strongest tornadoes on Earth.

Accordingly, many believe that life is unlikely to exist in the eye of Jupiter’s storm—the planet’s atmosphere contains large amounts of toxic gases such as ammonia, methane, and hydrogen sulfide, which are lethal to most forms of life.

Many believe that life is unlikely to exist in the eye of Jupiter’s storm.

In conclusion, while the possibility of life in Jupiter’s atmosphere cannot be completely ruled out, so far, no evidence of life has been found here.

However, some of Jupiter’s moons, such as Europa, are currently believed by scientists to potentially harbor subsurface oceans of liquid water beneath their icy shells.

Moreover, tidal forces and cryovolcanic activity caused by the moon’s surface interactions may create a perfect environment for some Earth organisms, or there may be microbial life existing here that we have yet to discover.