The practice of foot binding, also known as “lotus feet,” has been an extreme and painful tradition that haunted millions of Chinese women for centuries.

Three particularly strange phenomena in ancient China are courtesans, eunuchs, and foot binding. Among these, courtesans and eunuchs appeared in other countries as well; however, the practice of foot binding among women is one of the most unique customs, exclusive to ancient China.

The tradition of foot binding in ancient China began during the Northern Song dynasty, became widespread in the Southern Song dynasty, and reached its peak during the Ming dynasty. Most girls started binding their feet at the age of 4 to 5. By the time they reached adulthood, when their foot bones had fully formed, they could finally remove the binding cloth. However, many continued to have their feet bound until death.

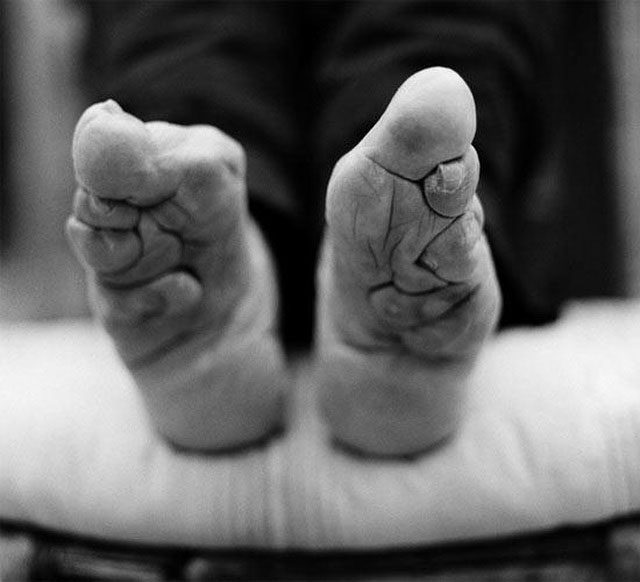

Women with bound feet endured immense pain.

In China, there is a saying, “a pair of small feet, a sea of tears,” implying that the practice of foot binding caused tremendous suffering for women. Traditionally, the binding process took place on the 24th day of the 8th lunar month for girls aged 4 to 5. Initially, the toes were bent inward towards the sole of the foot, except for the big toe. Then, they were tightly wrapped with strips of white cotton cloth. As the foot grew, the cloth would be tightened until the bones were broken and no further growth occurred.

The feet would be soaked in a mixture of herbs and animal blood to soften them, and the toenails were cut as short as possible. The toes on each foot were pulled back and pressed down, tightly against the sole until both the toes and the arch of the foot were broken. Afterward, the foot would be completely wrapped, pressing the toes down.

Unlike most other practices that involve temporary suffering during a procedure, foot binding resulted in lifelong pain for girls. It is estimated that around 2 to 4 billion Chinese women endured the agony of foot binding for over a thousand years.

The bones of their feet would remain fragile for many years and were prone to repeated fractures. Toenails were often cut too deeply, leading to infections. Women with bound feet were more likely to fall and suffer hip fractures as well as other broken bones. Many women with bound feet lived with long-term disabilities, enduring pain throughout their lives.

Lotus feet, created by bending the toes into the sole and tightly binding them with cloth, were once deemed a prerequisite for women to secure a good marriage and a better life, according to CNN. “Traditionally, the practice of foot binding existed to please men. Small feet were considered more attractive,” said Laurel Bossen, co-author of the book “Bound Feet, Young Hands.”

However, Bossen’s research indicates that the practice of foot binding was seriously misunderstood. Bound-foot girls did not enjoy a leisurely life but served a crucial economic purpose, especially in rural areas where many girls as young as 7 were required to weave fabric, spin thread, and perform other manual labor.

The enduring practice of foot binding can be attributed to clear economic reasons. It ensured that young women sat still and were willing to do tedious, monotonous production work such as weaving fibers, textiles, carpets, shoes, and fishing nets, which were the main sources of income for many families.

The lotus feet of a Chinese woman after her shoes. (Photo: Imaginechina).

The practice of foot binding began to decline only when mass-produced and imported fabrics replaced handcrafted goods. “You need to connect hands with feet. Women with bound feet produced valuable handicrafts at home. The image of them portrayed as idealized figures bringing pleasure is just a distortion of history,” Bossen stated.

Bossen, an honorary professor of anthropology at McGill University in Montreal, and her colleague Hill Gates at Central Michigan University, interviewed nearly 1,800 elderly women from various rural areas in China, the last generation of foot-bound women, to determine when and why this practice began to fade.

They discovered that foot binding persisted longest in areas where home weaving still held economic value and began to decline when cheaper, factory-produced fabrics became available in those regions.

Young girls started learning to weave fabric at ages 6 to 7, the same age they underwent foot binding. “My mother bound my feet when I was around 10 years old. By the age of 10, I started weaving fabric. Each time my mother bound my feet, the pain made me cry,” shared a woman born in 1933 with the research team.