The massive Colossus computer occupied the space of an entire room, reducing code-breaking time from several weeks to just a few hours.

The British intelligence agency GCHQ has released previously unseen images of Colossus, the British code-breaking computer that played a crucial role in helping the Allies win World War II, BBC reported on January 18. GCHQ released these images to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Colossus’s invention, which many consider the first digital computer. The series of images provides new information about the origins and functioning of the machine.

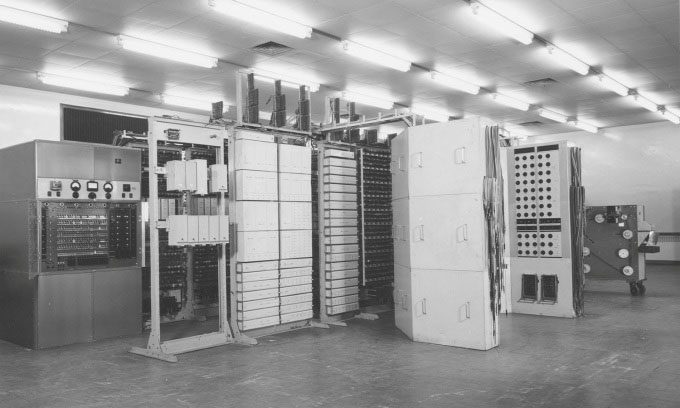

Colossus code-breaking computer. (Photo: Reuters/GCHQ)

The existence of Colossus remained a secret until the early 2000s. “Technological innovation has always been at the heart of our work at GCHQ, and Colossus is a perfect example of how our staff helped us lead in new technologies – even when we couldn’t talk about it,” said Anne Keast-Butler, GCHQ director.

Bletchley Park, the UK’s code-breaking center, successfully decrypted the Enigma code used by the Nazis. However, by 1943, the Germans were using a new, more complex coding system called Lorenz. Messages took up to 8 weeks to decode manually while the codes changed nightly, requiring the UK to develop a new electronic computer system to break the Lorenz code quickly enough.

British engineer Tommy Flowers spent 11 months designing and building Colossus at Dollis Hill in northwest London. After testing and verification, the Colossus Mark I version was transported to Bletchley Park in December 1943 – January 1944. There, the machine was installed by Harry Fensom and Don Horwood, and it became operational in early 1944.

The first version of Colossus was equipped with about 1,600 valves. It was so effective that by the end of World War II, around 10 units had been built, including a faster Mark II version with approximately 2,500 valves. It occupied the space of a living room, standing over 2 meters tall, about 5 meters long, and 3.4 meters wide. The machine weighed around 5 tons and used 8 kW of power, equipped with about 100 logic gates and 10,000 resistors connected by 7 km of wiring.

Colossus accelerated the decoding of the complex Lorenz messages from several weeks to just a few hours. Historians believe that the computer helped shorten the war. Colossus required a skilled team of operators and technicians for its operation and maintenance. By the end of the war, 63 million characters in high-level German messages had been decoded by 550 personnel working on the computers. After the war, 8 out of 10 computers were destroyed.

“From a technical standpoint, Colossus is an important precursor to modern electronic digital computers. Among those who used Colossus at Bletchley Park, many went on to become pioneers and key leaders in the computing industry in the UK in the following decades,” said Andrew Herbert, an expert at the British National Computing Museum.