Before the legendary flight of the Wright brothers, two British engineers successfully created a fixed-wing aircraft powered by steam engines.

In 1842, British engineers William Samuel Henson and John Stringfellow patented their aircraft. Unlike many previous attempts that utilized gliders and hot air balloons, the invention of Henson and Stringfellow was unique as it marked the first significant step toward powered flight. Just six years later, the world’s first steam-powered aircraft took to the skies. Notably, this occurred more than half a century before the historic flight of the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk, as reported by Amusing Planet.

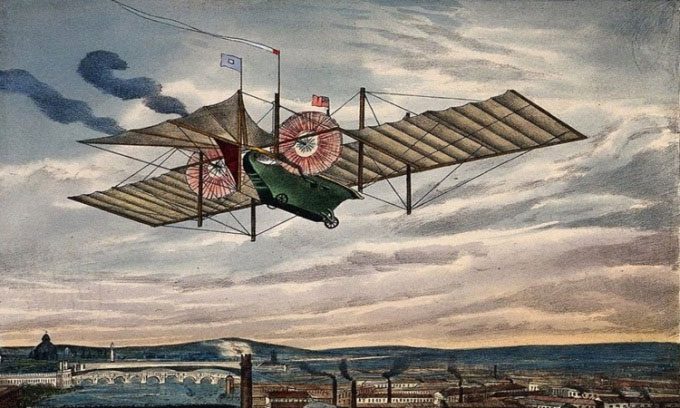

Simulation of a steam-powered aircraft flying in the air. (Photo: W. L Walton).

Humans have sought to fly since ancient times. In the 9th century, Muslim engineer Abbas ibn Firnas created a set of wings made from eagle feathers and managed to glide a short distance before falling and injuring himself. In the 11th century, Benedictine monk Eilmer of Malmesbury attached wings to his arms and legs, flew a short distance, and then crashed. By the late 19th century, a German sailor named Albrecht Berblinger fashioned wings attached to his arms and jumped into the Danube River, hoping to cross it. The result was that Berblinger fell straight into the water.

The first significant breakthrough in aviation came from Yorkshire baron George Cayley, who was the first to propose designing a modern aircraft as a fixed-wing machine rather than a flapping-wing contraption like many of his predecessors envisioned. Cayley suggested creating separate systems for lift, thrust, and control. He also identified four forces acting on an aircraft: thrust, lift, drag, and weight, and discovered the importance of curved wings for flight performance.

Inspired by Cayley’s work, John Stringfellow and William Samuel Henson designed a large passenger aircraft powered by steam engines. Named “Aerial,” it had a wingspan of nearly 46 meters and a weight of 1,360 kg according to the design. The thrust for the machine came from a lightweight steam engine created by Henson, capable of producing 50 horsepower. Henson and Stringfellow even planned to establish a company, Aerial Transit, with this fleet of aircraft, each capable of carrying 10-12 passengers across the Atlantic to Egypt and China.

In 1848, Henson and Stringfellow produced a scaled-down version of the aircraft with a wingspan of 3 meters and two engines driving six counter-rotating propellers at the rear. To prevent the aircraft from swaying due to wind, the engineers conducted experiments inside an abandoned factory in Chard. The testing space was approximately 20 meters long and 3.7 meters high, providing a controlled environment for their work. A guiding wire prevented the aircraft from veering off course. This wire occupied less than half the length of the room, leaving space at one end for the machine to take off from the floor. When the steam engine ignited, the machine moved along the guide wire, gradually rising before reaching the other end of the room, where it crashed into a canvas placed there to halt its movement. This was the first recorded flight in history performed by a fixed-wing aircraft powered by steam.

The flight was successful only once; subsequent attempts failed. Larger models built later could not achieve sustained flight, quashing hopes for the Aerial Transit passenger aircraft. Henson became discouraged and gave up, leading to the disbandment of the company in 1848. However, Stringfellow persisted in pursuing powered flight with his son, building another 3-meter-long model powered by a compact steam engine he designed himself. Numerous witnesses reported seeing the model ascend during several trials in 1848. Stringfellow himself remained confident in the experiments and viewed them as proof of the feasibility of powered flight.

Although Stringfellow’s contributions have largely been forgotten in the course of history, a bronze model depicting his invention is located on Chard’s Fore Street in Somerset, alongside many other models in the collection at the Science Museum in London.