“Mirus” in the name mirusvirus means “strange” in Latin, as scientists assert that they are a group of viruses that have never been seen before.

According to Live Science, preliminary research results indicate that the strange virus may be related to a large group of viruses known as Duplodnaviria, which includes familiar herpes viruses that infect animals and humans based on shared genes encoding the capsid.

However, this unusual virus also shares an astonishing number of genes with another gigantic group of viruses called Varidnaviria.

This suggests that they are likely a newly emerged hybrid product, researcher Tom Delmont from the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) told Live Science.

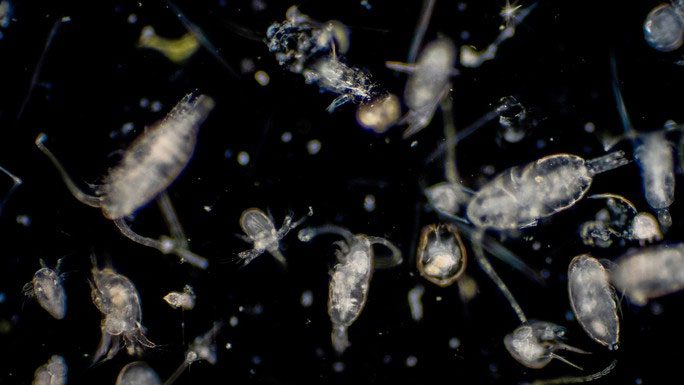

Image of a seawater sample showing the presence of various plankton, which may be carrying the strange virus – (Photo: LIVE SCIENCE).

Dr. Delmont’s team published their research in the scientific journal Nature on April 19, asserting that this new discovery confirms that humanity still knows very little about the world of ocean microorganisms.

The study also shows that this strange virus group is spreading across Earth’s oceans, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and is infecting plankton in areas they are gradually invading.

By invading the cells of plankton, they adjust their activities and significantly impact the flow of carbon and nutrients circulating in the oceans.

Their presence was identified through the analysis of data sets from the Tara Ocean expedition, an international project that collected nearly 35,000 seawater samples containing viruses, algae, and plankton from 2009 to 2013.

The research team searched for evolutionary clues in millions of microbial genes and discovered the mirusvirus, which they called an “evolutionary treasure.”

Scientists are still studying the strange virus and hope that it could be the key to unraveling the mysterious origins of herpes viruses that exist in the human body.

The genes encoding the protective shell around the DNA of both types of viruses are remarkably similar, indicating that they are related and may share a common evolutionary history. Understanding them could enhance our knowledge of some diseases caused by herpes in humans.