You may have heard of “The Ames Room,” one of the most famous and popular illusions in the world. In this illusion, as a person moves from one corner of the room to another, they suddenly transform from a tiny figure into a giant and vice versa.

Ames rooms like this are created from the same formula, and you can also design an illusion room like this at home if you have the means. It was discovered by Adelbert Ames, an American scientist who lived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Ames has an even more “confusing” illusion

However, what many people do not know is that Ames has an illusion that is even more “confusing.” It is designed very simply and is called the “Ames window“. This illusion not only makes you doubt your own eyes, but it can also raise questions about reality, science, the universe, and our own human physics.

The Ames Window illusion and the mysteries behind it.

1. The Ames Window

This illusion was designed by Adelbert Ames in 1947 while he was researching how human vision interacts with architectural forms. Ames discovered that in reality, we see rectangular objects, such as windows, doors, walls, and paintings, as trapezoidal from most angles (except for a direct view). However, our brain still recognizes them as rectangles in every case.

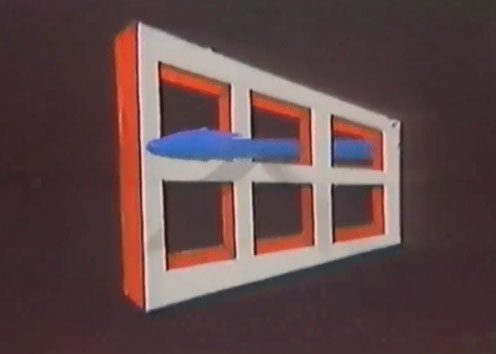

Therefore, Ames created a trapezoidal window frame with one long side and one short side. Essentially, it is a 2D cardboard piece, painted uniformly on both sides to create a 3D effect. He then placed the window on a rotating table, setting it to spin continuously at a constant speed.

However, when an observer is positioned at eye level with the window, they will see it not rotating 360 degrees, but rather swaying back and forth at a 180-degree angle. In other words, the window rotates to one point, then stops, reverses direction to another point, and continues this way.

The illusion reaches its peak when you place a metal ruler or a plastic pen through the center of this window frame. As a result, you will see the ruler spinning while the window continues to sway back and forth.

To achieve this, the ruler must clearly pass through the window—something your eyes perceive, but your brain cannot believe. This scenario is quite absurd; the ruler is fixed to the cardboard piece and cannot possibly spin through it.

2. Why Does This Illusion Occur?

In Ames’s 1949 work “Building for the Modern Man,” he explains that the illusion of the window arises from our familiarity with living in rectangular boxes.

From houses, walls, windows, doors, to furniture like tables, chairs, cabinets, and picture frames, everything is composed of rectangles with right angles everywhere.

This kind of world is referred to as a “carpentered environment“, created since humans learned to flatten their wooden doorframes.

However, if you pay close attention, the rectangles in our world are rarely perfect rectangles from your viewpoint. Unless you look directly at a window, at other diagonal angles, the image of the window on your retina is actually a trapezoid, not a rectangle.

Nevertheless, because our brains are so accustomed to the “carpentered environment,” they still interpret these as perfect rectangles. The distortion of the trapezoid is now used by the brain to infer the depth of the scene. The more a rectangle is distorted, the more you understand that you are viewing it from a distance, or in other words, it has greater depth.

The more a rectangle is distorted, the more you understand you are viewing it from a distance.

Returning to the Ames window, you see it is a trapezoid with one long side and one short side. Normally, when viewing a real rectangle from an angle, we see the side nearer to us as longer, while the side farther away appears shorter. This is the typical understanding of depth in the environment and objects.

However, with the Ames window, when it spins continuously, the long side, although pushed farther away, still appears longer than the short side, even when viewed from a distance. Therefore, our brains continue to think that it is still closer.

At the point where the cardboard rotates backward, the overlap or confusion about the perception of depth leads to the rotating cardboard appearing to stop and flip over to change direction instead of spinning as it actually does.

Ames’s “carpentered environment” hypothesis has been tested with indigenous communities in South Africa, where they live in a “non-carpentered” world, with round huts and square windows appearing less frequently.

The results showed that children growing up in this environment are indeed less affected by the Ames window illusion compared to age-matched children growing up in cities in South Africa. This is because their perception of depth using trapezoids occurs less frequently.

3. Doubts about Our Senses and the Universe

Since its invention, the Ames window illusion has sparked a debate about vision. It also forces us to question our perception as well as humanity’s scientific foundation.

Accordingly, scientists work by observing events, formulating hypotheses, and testing them through real-world experiments. For instance, Albert Einstein used his theory of relativity to predict the presence of gravitational waves. More than 100 years later, scientists finally observed experiments that proved his theory.

However, the Ames illusion suggests a possibility: human observations are actually just our species’ subjective observations and cannot be objectively verified without confirmation from other “human-like” species.

This means there could be countless realities producing a subjective observation, but we only understand that as a single reality. For example, when ancient people observed the Sun moving across the sky, they mistakenly thought the Sun revolved around the Earth, when in fact it was the Earth rotating on its axis.

The Ames illusion forces us to question our perception and humanity’s scientific foundation.

Modern science recognizes that the speed of light in a vacuum is constant and the same in all directions, based on observations and experiments. But could there be another reality that yields such observational results?

In that reality, light is just playing tricks on us. Photons move faster at times, slower at others, but they all reach their destination at the same time with an average speed of approximately 300,000 km/s.

And when you conduct a quantum measurement, like the Schrödinger’s cat experiment, at the moment you observe its state as alive or dead, is there a reality where its state remains superimposed, both alive and dead? Just like the Ames window illusion, spinning and swaying at the same time?

Or must reality branch into two universes, one where the cat dies and another where it remains alive? And in another universe, we might see more round houses than rectangular ones, leading to fewer occurrences of the Ames window illusion. People living in that universe would also see the window as actually spinning more at all angles rather than flipping back and forth.

The Ames room illusion operates by manipulating the signals our brain uses to determine the distance and size of an object. The unusual shape of the room and the angles create a distorted image that our brain must try to interpret. It must reconcile what it sees with its understanding of how the world should look. This mismatch leads the brain to perceive objects in the room as being different sizes from their actual sizes.

The Ames room was first built in 1934 by psychologist Adelbert Ames Jr. Notably, the Ames room was used in the filming of “The Lord of the Rings” to adjust the size of the Hobbits relative to Gandalf. The Ames room is also described in the 1971 film adaptation of Roald Dahl’s novel “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.”