In today’s era of strong globalization, knowing multiple foreign languages is a prerequisite for individuals to integrate, develop, and keep pace with the progress of the times. The world has approximately 7,000 languages, among which Chinese, Spanish, and English are the most widely used. Have you ever thought that in 100 years, one of these three languages will be spoken by everyone around the globe?

>>> 50 Years, 220 Languages “Disappeared” in India

At that time, people will travel around the world more easily and conveniently than ever before. A linguist, philosopher, and musician at Columbia University in the United States has conducted a profound and interesting study on the historical evolution of language. Through this, he outlines a vision of what global language might look like in 2115.

The Hope of an International Language Beginning in the 1880s

In 1880, a priest from Bavaria in southern Germany created a new language called Volapük, hoping it would be adopted by everyone worldwide. Volapük is a blend of words from English, French, and German. However, it was very difficult to use, hard to pronounce, and had a grammar structure as complicated as Latin. A few years later, Volapük quickly fell into obscurity and made way for another newly invented language, Esperanto. Addressing the shortcomings of Volapük, Esperanto was easier to learn, with students typically taking only one session to grasp the basic rules.

However, by the time Esperanto began to be introduced, English had quickly become the international language of communication. Two thousand years ago, Old English was spoken by Iron Age tribes in Denmark. Yet, a thousand years later, English was overshadowed by French right on the British Isles. At that time, no one thought English would become as popular as it is today, with over 2 billion speakers, equivalent to one-third of the world’s population.

An illustration of the Babel Tower legend, which led to the division of human languages.

A legend in the Bible tells that once, after the Great Flood, humans gathered together in the city of Babylon. They spoke the same language and began to build a massive Tower of Babel that was “so tall it could reach heaven.” However, Jehovah thwarted their intention by confusing their language, making it impossible for them to understand one another, thus breaking their plan to build the tower. From then on, humanity spread out across the globe, each region speaking thousands of different languages.

Some films and science fiction novels often depict a planet where all residents speak a common language. Therefore, some people fear that English may gradually extinguish other languages, becoming a “language of Earth”, leading humanity to lose thousands of languages tied to the history and culture of each nation. However, this fear may be premature. In reality, changing the language of an entire nation is not easy, especially when that language has been used naturally by its people since birth.

Despite the widespread use of English today, most people use it as a language for external communication, while local languages continue to be utilized in their own unique spheres. But the question remains: what language will humanity use on this planet a century from now, in 2115? Two hypotheses have been proposed to describe the linguistic landscape a hundred years later. The first is that only a few languages will remain. The second is that languages will evolve to be simpler than they are today, especially in terms of spoken forms differing significantly from written forms.

Will Chinese Become an International Language?

An English class for students in Gansu, China. Some believe that Chinese will become the international language in the future. However, its complexity makes this difficult to achieve. (Illustrative image)

Some believe that it is not English, but Standard Chinese that will truly become the world’s language. The idea here is based on the enormous population of the country combined with its rapidly developing economy. However, this seems not to be an easy feat, as English has already established a solid foundation. English is deeply entrenched and has become a model in many different fields, making any shift to a new language a significant effort. We already have the “international keyboard” QWERTY and the AC power standard for this reason.

Moreover, Chinese is extremely difficult to learn without early exposure, and mastering the logographic writing system is not straightforward. In fact, not just Chinese, but languages like Greek, Latin, Aramaic, Arabic, and Russian are also seen by many learners as particularly challenging languages. Coupled with the foundation that English has built, Chinese is unlikely to become close enough to replace English as the international language. History has shown that many powerful forces have occupied and ruled a region without changing its language. The Mongols and Manchus ruled China, yet Chinese remained intact.

Complex Languages May Gradually Fade Away if Not Passed to Future Generations

Illustrative image

Some predict that by 2115, there will only be 600 languages left in the world instead of the current 6,000 (about 1,000 of which are believed to be gradually disappearing). Some languages spoken by small groups of people will face difficult situations. Historically, most languages of the indigenous peoples of the Americas or Australia have been assimilated by English. Additionally, the rapid urbanization seen today further accelerates this process. As people migrate to major cities and urban centers, they gradually must adopt a common language for communication.

On another note, contemporary thinking often suggests that a language must be used in writing, with established rules and structures strictly followed, to be considered a language. Those who can only speak but cannot write are often not regarded as truly “knowing” or using a language. For instance, Yiddish (an old German language of Jews in Central and Eastern Europe) is considered a dying language, even though many people still use it for communication in Israel and the United States but do not know how to write it.

In an environment with a dominant language that is more prevalent than each individual’s native tongue, there is a tendency for people to use the dominant language more frequently, leading to their native languages being deemed outdated. As a result, it is highly likely that their native languages may not be used to communicate with their children. For example, if an adult from Country A moves to Country B, they will start using the language of Country B. If they do not speak Language A to their children, the next generation will not inherit Language A. Naturally, by the time they grow up, Language B will be the native language of their children.

However, it is precisely children who are crucial to preserving the vitality of any language. Whether it is English with its myriad irregular verbs and exceptions, Chinese with its logograms and four tones, or even Hmong with its eight tones, children can learn them easily. Yet, a reality is that many communities are increasingly neglecting the importance of effectively teaching their languages to children.

A Wave of Optimizing Native Languages

Illustrative image

Instead of maintaining a difficult, outdated language that is on the verge of extinction, many communities, including schools and adults, have adapted a new version of the language by simplifying vocabulary and grammatical structures. In the past, many languages have been preserved in this manner. History has recorded strong waves that contributed significantly to the transformation of languages toward simplification. The first wave was the development of technology, which allowed people to cross oceans, invade, and settle in new lands.

For example, when the Vikings invaded England in the 8th century, they began to integrate into society. At that time, education was limited to the nobility, so ordinary parents gradually began to “break” Old English when teaching their children. These children would grow up speaking a new version of English. In Old English, there were up to three genders, five cases, and an extremely complex grammatical system, comparable to modern German. However, after the Vikings arrived, it evolved into Modern English – one of the few languages in Europe that no longer uses gender in inanimate objects. Similarly, Chinese, Persian, Indonesian, and many other languages have entered a similar cycle aimed at simplifying the original language.

In the subsequent era, the second wave brought African slaves to Europe, which once again significantly impacted the language transformation process here. At that time, adult black individuals needed to quickly learn a new foreign language, even more simply than the Vikings. They only required a few hundred vocabulary words and some basic grammatical structures. From these initial principles, they began to develop a new language that could endure in Europe: Creole emerged – a form of pidgin.

In fact, Creole languages were created worldwide during the era of “Western colonization.” Haitians created Haitian Creole from French, African soldiers developed Arabic Creole in Sudan, and people in New Guinea created German Creole. Indigenous Australians also developed English Creole, which spread to surrounding areas, reaching New Guinea with the name Tok Pisin – now recognized by the government as the national language.

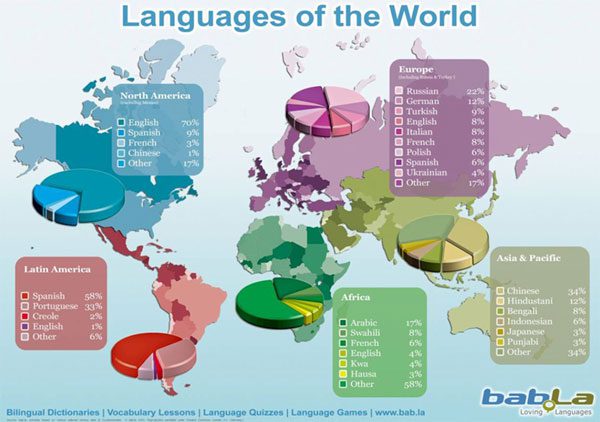

World language map. (Source: Bab.la)

Next, the wave of modern migration once again propelled the third modernization of language. Immigrant children in cities around the world began to speak languages that blended the original local language with the version spoken by their parents. In other words, the next generation would once again transform the indigenous language into their own. In this way, Kiezdeutsch – a local dialect in Germany transformed into “Kebob Norsk” when it reached Norway. Another example is Singapore’s “Singlish – the English of Singaporeans.” The world witnessed the emergence of “lightly adapted” versions of old languages.

This form of adaptation is not a degeneration of language. Most of the new “optimized” languages fully adhere to the rules of the original language, and when a speaker of Old English hears the new version, they will recognize that it has been modified but still maintains balance. However, these modifications lean toward being less cumbersome, containing fewer irregular verbs, fewer tones, and, of course, lacking the categorization of nouns by gender.

This may very well be the trend of language transformation in the world in the future. The issue at hand is that all transformed languages still need to be documented and preserved comprehensively using modern tools for future generations. We must not reach 2115 and regret a world that once had 6,000 languages but now has only 600. And this is merely a prediction; currently, people are using one language alongside their native tongue for international communication.

Ultimately, it seems that people often recount the story of the Tower of Babel as a curse for humanity rather than a blessing. The future promises continued transformation of language towards optimizing a single language in many different ways. At that point, new versions will still be able to communicate easily with one another. The future may not be a rigid English for the entire world but rather a flexible English that emerges from many diverse regions, blending and intertwining.