A 3-ton Digital Camera Successfully Completes Its Journey by Plane and Truck to Reach an Observatory at Over 2,700m Above Sea Level.

After two decades of development, the centerpiece camera of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory has arrived at its home last week. The camera is now located on the Cerro Pachón in Chile. This camera is the final critical component of the Simonyi Survey Telescope at the Rubin Observatory. There, the equipment will be installed after several months of thorough testing. The safe and successful transport of this SUV-sized camera from its manufacturing site at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California to its mountaintop location in the Andes, Chile, is no small achievement, according to Space.

The journey of the LSST camera from California to Chile. Video: (Rubin Observatory).

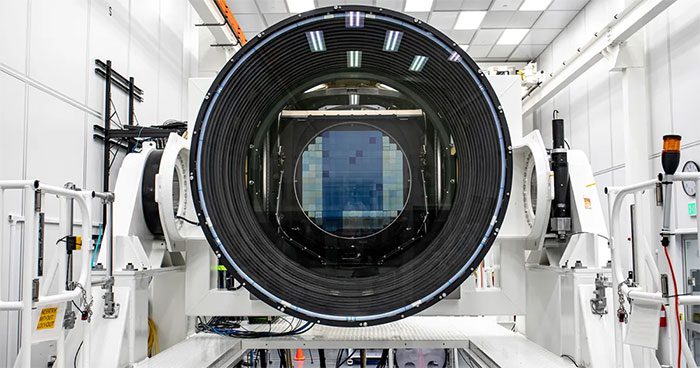

This is the largest camera ever built for astronomy, weighing 3 tons and measuring 1.5 meters in width. To minimize risks to the $168 million device, scientists and engineers conducted a dress rehearsal in 2021 by transporting a weight-equivalent mock-up to Chile. The mock-up was equipped with data recording devices to capture the conditions that the actual camera would experience throughout the journey.

“Transporting such a sophisticated device around the world involves many risks. With 10 years of camera assembly, culminating in a 10-hour flight and the winding dirt road up the mountain, proper transportation is crucial,” said Margaux Lopez, a mechanical engineer at SLAC responsible for planning the camera’s transport. “However, due to our experience and data from the test transport, we were confident we could protect the camera safely.”

On May 14, the camera was transported to San Francisco International Airport for its 10-hour flight to Chile. The equipment was flown on a Boeing 747 cargo plane, landing the next day at Santiago International Airport in Chile, the closest airport to the Rubin Observatory capable of accommodating such a large aircraft. The following evening, the camera and a convoy of 9 trucks were safely inside the gate at the Cerro Pachón station. The next morning, the equipment began its 5-hour journey along a winding 35 km dirt road to the mountaintop at an elevation of over 2,713 meters above sea level.

“Our goal was to ensure that the camera not only arrived intact but also in perfect condition,” said Kevin Reil, a scientist at the Rubin Observatory. Subsequent checks confirmed that the camera did not encounter any unexpected pressures during the long journey. According to Reil, initial readings from the data logger, accelerometer, and shock sensors indicated that they had succeeded.

LSST Camera.

The successful arrival of the camera at the observatory is great news not only for all the scientists and engineers involved in the project but also for the next generation of astronomers eager for the observatory to begin operations, expected by the end of next year. This is when the Rubin Observatory will conduct a decade-long survey of the universe by capturing panoramic images of the southern sky several nights a week, cataloging about 37 billion objects. This survey is called the “Legacy Survey of Space and Time.”

The LSST camera set a world record in 2020 with the largest image taken by a giant digital camera. Scientists say that just one of its 3,200-megapixel images requires 378 4K ultra-high-definition TVs to display. Its resolution is so good that it can detect a golf ball from a distance of 25 km. Using data from the 10-year survey, astronomers hope to gather clues about the nature of dark matter and dark energy, which account for over 90% of the universe’s mass but have yet to be directly detected. Most importantly, the LSST camera will search for and study signs of weak gravitational lensing, a cosmic phenomenon that occurs when a large galaxy bends or distorts light from a background galaxy.