Exclusive to the Amazon River basin in Brazil, Ipe trees produce the most expensive wood in the world. On the market, one cubic meter of Ipe wood costs $3,775 (approximately 90 million Vietnamese Dong). A staggering 96% of the world’s Ipe wood supply comes from Brazil. Consequently, illegal logging gangs in Brazil are aggressively hunting this wood, leading to the increasing endangerment of the Ipe tree.

According to the International Tropical Timber Organization, biologically, Ipe trees typically grow alone, interspersed with other species, and it takes between 80 to 100 years for them to reach a trunk diameter of over 1 meter. Ipe wood is resistant to termites, fungi, and high humidity, and it is also difficult to ignite, making it highly sought after in markets across Europe, the United States, and Canada.

Ipe trees being transported to a sawmill.

This wood is commonly used for flooring, wall paneling, staircases, steps, furniture, or interior decoration on luxurious yachts. It has even been used to line the interior of a private jet owned by an oil tycoon in the Middle East with thin Ipe wood panels!

Due to its high price, Ipe wood is a lucrative target for illegal logging gangs in Brazil. The International Tropical Timber Organization reports that Brazil has seven types of Ipe trees, with the cheapest priced at $1,752 per cubic meter, and the most expensive at $3,775. Between 2017 and 2021, at least 525 million cubic meters of Ipe wood were exported abroad.

A report released on July 18, 2022, indicates many signs that Ipe trees are at risk of extinction. Luciano Evaristo, director of Brazil’s environmental protection agency, stated: “On average, one hectare of forest in Brazil contains only 0.5 cubic meters of Ipe wood. This means that loggers have to clear forest to create paths for cranes, with some stretches extending over 10 km just to fell one Ipe tree.”

Following a group of loggers, a reporter from Latin America Today described the logging process: “First, two or three individuals scout for Ipe trees. They are equipped with modern tools, including GPS devices, satellite phones, food, and waterproof tents. Each trip can last a week, or even 10 to 15 days. Upon discovering an Ipe tree, they mark its location and continue searching for more. Once they find 10 to 15 trees with sufficient diameter to yield several dozen cubic meters, they head back.”

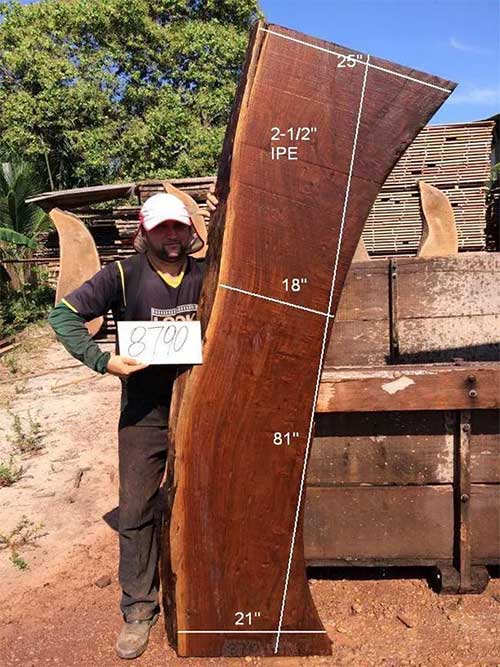

A piece of Ipe wood for sale at $8,700.

Based on this information, the logging gang will plan the route to open paths for the crane. To avoid detection by satellites and forestry authorities, the width of the path is just enough for a vehicle to pass. Taking advantage of the solitary growth pattern of Ipe trees, the loggers use cranes with steel arms to grip the tree trunk, and once it is cut, the steel arm lowers the trunk to the ground without toppling nearby trees, making it difficult to detect from satellite images. After the tree is felled, the crane transports it to a collection yard for trucks to take it to processing sites. The “blind eye” turned by some forestry officials leads to enormous profits from Ipe wood, resulting in the term “Ipe mafias” to describe the logging gangs operating in the Amazon basin.

To facilitate exports, the “Ipe mafias” collude with some legally operating logging, processing, and export companies to create “ghost” surveys, inflating the number of Ipe trees in a specific area by tens of times. Subsequently, the “Ipe mafias” connect with certain forestry officials to certify permits for logging.

In May, the Brazilian government faced accusations of not only turning a blind eye to illegal logging in the Amazon but also actively participating in such activities. The Minister of the Environment was investigated and resigned, while the head of the Environmental Protection Agency (IBAMA) was suspended. Both were accused of facilitating excessive logging by export companies, including Ipe wood.

Currently, logging of Ipe wood continues silently but in large quantities in northern and western Pará, north of Mato Grosso, north of Rondônia, and southern Amazonas. The federal government of Brazil permits logging in 2.5 million hectares of Ipe forest, but estimates from the International Tropical Timber Organization indicate that illegal logging operations have cleared up to 16 million hectares, six times the permitted area.

A spokesperson for the International Tropical Timber Organization stated: “The high value of Ipe wood has incentivized illegal logging, leading to other types of crime.” Furthermore, without transparency and public data, it is challenging to distinguish between legally and illegally sourced Ipe wood from five of the seven states with significant Ipe populations in Brazil. Stopping the extinction of Ipe trees requires more robust action.

Daniel Bentes, director of the Brazilian Forestry Companies Association, noted that permits provide only 2% of the domestic natural wood supply. This figure is minimal compared to the potential of 35 million hectares of native forest. Thus, where does the remaining 98% of wood come from if not from illegal logging? Daniel Bentes stated: “Addressing this situation depends on assessing the current and future Ipe wood reserves, at least for the next 50 years, to plan sustainable logging, as the growth rate of this tree species is very slow. If management continues as it is now, companies involved in logging and processing, as well as forest protection communities, will not be able to stop the activities of the ‘Ipe mafias.’”