Due to climate change, rising sea levels are infiltrating a nuclear waste storage site of the United States on the Marshall Islands in the Pacific. The risk of leaking radioactive materials left over from some of the largest atomic tests in history is becoming evident.

Ms. Christina Aningi, the principal of the only school on the coral island of Enewetak (part of the Marshall Islands), stated: “In the schoolyard, students sit on the sand, innocently singing about the island, about the coral, the sun, the wind, and the swaying palm trees. They were born decades after the last nuclear explosion in the Pacific. But we call it a tomb. The children do not understand that this is a place that can spread toxins. The haunting memories that seemed buried long ago are threatening to resurface.”

On the western island of the Marshall Islands (located between Australia and Hawaii) lies a structure resembling a “dome”. From the outside, it is difficult to assess the true scale of the concrete dome as its surface is obscured by palm and date trees. However, from above, it resembles a massive flying saucer that has landed on the tip of a deserted island. Buried beneath are 85,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste – a toxic legacy from the early days of the atomic age.

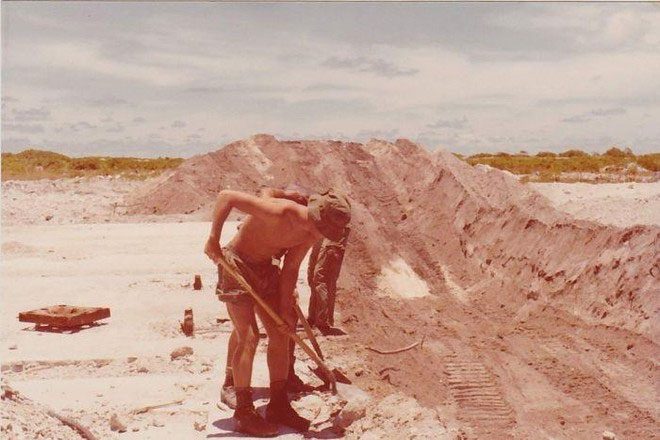

The U.S. military buried nuclear waste in Runit over 40 years ago.

“The Dome” on the Coral Island

In the late 1970s, Enewetak was the site of the largest nuclear waste burial in U.S. history. Heavily contaminated debris left over from dozens of atomic tests was dumped into a hole over 100 square meters wide at the tip of the deserted island. U.S. military engineers sealed it with a half-meter thick concrete cap, nearly the size of a football field, and then left the island. Now, with rising sea levels, water has begun to penetrate the dome.

The U.S. conducted 43 atomic bomb tests around the island chain in the 1940s and 1950s. Four of the 40 islands in the Enewetak Atoll were completely vaporized after the tests. Each thermonuclear explosion left a crater 2 kilometers wide, resembling a volcanic mouth, even though it was once a small island. At that time, the residents of Enewetak were relocated to another island in the Marshall Islands prior to the tests. More than 30 years later, these residents were allowed to return home. During the handling of nuclear waste, Washington allocated a budget to construct the dome as a temporary storage facility, with the initial plan to line the bottom of the crater with concrete. However, this option was later deemed too expensive.

Mr. Michael Gerrard, Chairman of the Earth Institute at Columbia University (New York), noted: “The bottom of the ‘dome’ is just what remains after the nuclear weapon exploded directly into it. It is soil, which is permeable, and there is nothing lined beneath it. Therefore, seawater can infiltrate.” Local residents rarely set foot on Runit Island, where this “dome” is located. They fear that radiation levels exceed safe limits. To this day, only three islands along the Enewetak Atoll are considered safe for human habitation. Mr. Giff Johnson, who works at the Marshall Islands Journal – the only newspaper in the country, stated: “Other islands have too many concerns about radiation. Such burial methods are ineffective.”

The Runit dome is at risk of seawater infiltration due to climate change.

Nuclear Legacy in the Age of Climate Change

After the atomic tests, the people of Enewetak lost their traditional fishing and subsistence environment. The waters that once supported their livelihoods are now polluted. On the main island, concerns about radioactive contamination of the food chain have led people to avoid eating fish and coconuts. The U.S. Department of Energy even banned the import of fish and coconut meat from Enewetak due to pollution. Most food is now brought to the island by barge, meaning that the islanders rely on imported processed and canned goods. The shelves of the only store in Enewetak are mostly filled with chocolate bars, marshmallows, and American-brand potato chips.

For the past 30 years, Jack Niedenthal has helped the nearby Bikini Atoll residents fight for compensation for 23 atomic tests conducted there. Niedenthal said: “This could pose significant problems for the rest of humanity if all that stuff sinks beneath the sea. Because that is Plutonium.” Some debris buried beneath the “dome” includes Plutonium-239, a fissile isotope used in nuclear warheads, one of the most poisonous substances on Earth. It has a radioactive half-life of 24,100 years.

From the top of the “dome,” one can gaze out over the ocean, where the gentle waves of the Pacific are lapping softly. A bomb crater from another atomic test cuts deep into the coral just a few meters away. Although access to Runit Island is officially restricted, the “dome” area remains unprotected and lacks warning signs. Its location right at the shoreline increases the vulnerability and exposure of this nuclear waste storage site. Visible cracks can be seen on the surface of the “dome” and puddles around its edge.

Mr. Michael Gerrard from Columbia University shared: “The U.S. government has acknowledged that a major storm could destroy or wash away the ‘dome’, dispersing all the radiation contained within.” While Professor Gerrard wants the U.S. to reinforce the “dome,” a 2014 U.S. Government report stated that if the structure were to fail, it would not change the pollution levels in the surrounding waters. Professor Gerrard remarked: “I am convinced that the radiation outside the ‘dome’ is as bad as the radiation inside it. Therefore, a tragic irony is that the U.S. government may be correct that if this material is dispersed, the already poor environmental conditions around it will not worsen.”

But that is a cold comfort for the people of Enewetak, who fear they may have to relocate once again if the “dome” collapses. Principal Aningi stated: “It just needs to crack, and most people here will no longer exist. It feels like a graveyard to us, and that could happen at any moment.” A report by the U.S. Department of Energy in 2013 indicated that radioactive materials are threatening the already fragile existence of the Enewetak people.

“That dome symbolizes the connection between the nuclear age and the age of climate change. The consequences will be catastrophic if it actually leaks. We are not just talking about the Marshall Islands; we are talking about the entire Pacific” – Alson Kelen, a climate change activist from the Marshall Islands, stated.

|

“That dome symbolizes the connection between the nuclear age and the age of climate change. The consequences will be catastrophic if it actually leaks. We are not just talking about the Marshall Islands; we are talking about the entire Pacific.” Alson Kelen – climate change activist from the Marshall Islands. |