Phthalates are widely used in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics to produce items such as plastic films and sheets, inflatable toys, blood bags, medical tubing, and especially children’s toys. So, what are phthalates, and are they harmful in children’s products?

1. What are Phthalates?

Phthalates are a group of chemicals most commonly used to make plastics more flexible and less brittle. They also serve as a binding agent or solvent. Phthalates are also known as plasticizers; they are found in many products and were first introduced in the 1920s as an additive in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and some healthcare products, such as insect repellent.

Exposure to phthalates is common, and studies from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have found that phthalates are present in a large portion of the population, especially among children and women of childbearing age.

Phthalates are found in a wide array of cosmetics and personal care products (shampoos, perfumes, nail polishes, hair sprays, sanitary pads, etc.), vinyl flooring, mini blinds, wallpaper, raincoats, medical equipment and devices (including blood storage bags and IV tubing), plastic tubing, shower curtains, plastic wraps, and food and pharmaceutical packaging, lubricants, and detergents.

Phthalates are believed to leach into food products through plastics used in food packaging and production facilities; researchers at the University of Washington reported in 2013 that phthalates were found in food, particularly in dairy products and spices.

Scientists from the Canadian Wildlife Agency have discovered that phthalates are widespread in the food chain and were found in the eggs of Arctic birds in Canada.

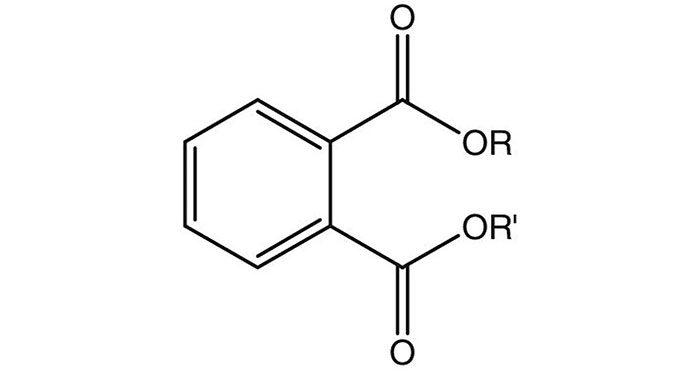

General chemical structure of orthophthalates. (R and R’ represent general sequences).

2. How do Phthalates Enter Our Bodies?

Phthalates are all around us, and both adults and children are likely to absorb them. Sheela Sathyanarayana, an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington and the lead author of a study examining phthalate exposure through baby care products, stated: “Children are particularly vulnerable to phthalate exposure due to their hand-to-mouth behavior and playing on the floor while their nervous and reproductive systems are developing rapidly.”

Here are the ways we all come into contact with phthalates:

- Ingestion. When children suck or chew on objects containing phthalates (like pacifiers or squeeze toys), or when they handle these toys and then suck their fingers, the chemicals can enter their bodies. Since children often put objects in their mouths, they are particularly susceptible to ingesting phthalates. Trying to keep children from putting objects in their mouths is not a good solution, as this is a crucial part of how they learn about their world. Instead, parents can remove potentially harmful objects from their child’s reach and ensure that toys and other items that are put in the mouth are completely safe. Older children also ingest phthalates when they play with items that contain them and then put their hands in their mouths. Polymer clay is one example. These clays are often marketed to children and are primarily made of PVC. We also ingest phthalates when consuming food contaminated through certain food packaging or when drinking beverages from plastic bottles that leach chemicals into food or liquids.

- Absorption. Phthalates are found in many scented products and cosmetics, where they help stabilize fragrances, enhance scent dispersion, and improve absorption. Therefore, you will find phthalates in deodorants, nail polishes (to help prevent cracking), hair sprays (to help hold hair), perfumes, moisturizers, creams, and powders (including baby creams and powders). Chemicals from these products can be absorbed through the skin and into the bloodstream. In 2002, a coalition of public health and environmental groups tested 72 branded cosmetics available for sale for phthalates. They found that nearly three-quarters of the products contained phthalates. When the CDC tested phthalate levels in people, they found the highest levels of phthalates in women of childbearing age, likely due to their use of cosmetics.

In a study published in the February 2008 issue of the Journal of Pediatrics, researchers at Seattle Children’s Hospital of the University of Washington and the University of Rochester found that children whose mothers recently used baby care products such as lotions, shampoos, and powders were more likely to have phthalate in their urine than those whose mothers did not use these products.

Exposure to phthalates is also common during hospital stays. Many medical devices, such as catheters and IV equipment, are made from PVC (polyvinyl chloride or vinyl) – including those used in NICUs and other pediatric and neonatal care areas. Because phthalates can leach into the fluids stored in these devices, such as blood, plasma, and intravenous solutions, the FDA issued a recommendation in 2002 for healthcare providers to avoid using DEHP-containing bags, IV syringes, and other devices when treating preterm infants and pregnant women carrying male fetuses. Accordingly, some hospitals are now removing PVC containing phthalates from their neonatal intensive care units.

- Inhalation. Phthalates can be inhaled from dust or fumes from any product containing vinyl plastic, such as vinyl flooring, vinyl car seats, and some diaper changing mats. The release of fumes from these products is known as off-gassing.

Of course, phthalates are also a concern for adults. Additionally, phthalates can cross the placenta, so they can be transmitted to the baby during pregnancy when the mother is exposed to this chemical. They can also be passed through breast milk, making it important for mothers to learn how to limit their exposure to protect their children. Breast milk is still the best food for infants. Phthalates should not deter breastfeeding, but they are a reason for mothers to read product labels to identify whether they contain phthalates.

3. Can Phthalates Be Harmful?

The effects of phthalates on humans have not been extensively studied, but they are believed to be endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that can alter hormonal balance and potentially lead to reproductive and developmental health issues, among other problems.

The National Research Council of the United States reported in a 2008 risk assessment that a link was found with reproductive and genital abnormalities, lower sperm counts, hormonal disruptions, and infertility.

According to two recent studies from Harvard, exposure to phthalates may increase the risk of miscarriage and gestational diabetes in pregnant women.

In infants and children, phthalates have been associated with allergies, male genital deformities, early puberty, eczema, asthma, lowered IQ, and ADHD. A 2010 study of New York schoolchildren linked prenatal phthalate exposure to later social functioning impairment. Last year, researchers in South Korea found, through a review of existing studies, a “significant association” between DEHP exposure and adverse effects on neurodevelopment in children.

Other studies have linked phthalates to other effects in adults. A research team led by Harvard concluded in a 2008 study that certain phthalate levels were associated with DNA damage in sperm from men at a fertility clinic. The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission stated in a 2014 risk report that exposure to certain phthalates could have adverse effects on thyroid, liver, kidney, and immune system functions. Some phthalates, like DEHP, one of the most widely used phthalates, have been classified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as possible carcinogens.

Phthalates are linked to early puberty issues in children.

4. How Can Consumers Minimize Risks?

Most exposure to phthalates comes from eating and drinking contaminated food, leading to the absorption of this chemical. Phthalates can also be inhaled from fumes of scented cosmetics or hygiene products absorbed through the skin. Because they are found in so many products, completely avoiding phthalates is challenging.

Minimize exposure by avoiding plastic food containers (plastics labeled with recycling codes 1, 2, 4, or 5 are probably the safest).

Instead, use glass containers and never heat food in plastic.

Check product labels and avoid any items containing phthalates.

When using baby care products, choose phthalate-free options. Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to identify from the ingredient list in products. Manufacturers are not required to list phthalates separately, so they may be included under the term “fragrance.”

Choose alternative foods to canned products, such as fresh fruits and vegetables and those stored in glass containers.

Avoid purchasing vinyl (PVC, polyvinyl chloride) plastic products, especially those that may remain in a child’s mouth, such as pacifiers, teats, or toys. Instead, opt for items made from the most natural materials possible. When buying plastic, look for types made from polyethylene or polypropylene rather than vinyl or PVC.

When painting or using other solvents, ensure that the area is well-ventilated and that your child is in a different location. Most paints contain DBP (dibutyl phthalate) to enhance their spreadability. You can search for natural paints that do not include this ingredient.

Choose shower curtains, raincoats, furniture, and building materials that limit vinyl whenever possible. Chemicals released from these products emit phthalates into the air, which can be inhaled by your child or you.

Clean regularly. Phthalates can linger in the air and in the dust in your home, so wet wiping can help remove these chemicals.