The Ancient “Time Capsule” buried from one of the most horrific volcanic disasters in human history has been unearthed on the coast of Turkey, providing new “fascinating” evidence about the Cataclysmic Event – The Great Flood.

In a paper published on December 28, 2021, by the National Academy of Sciences, a group of international researchers presented evidence of a devastating tsunami that occurred after the volcanic eruption of Thera (modern-day Santorini, Greece), a volcanic island in the Aegean Sea, around 3,600 years ago.

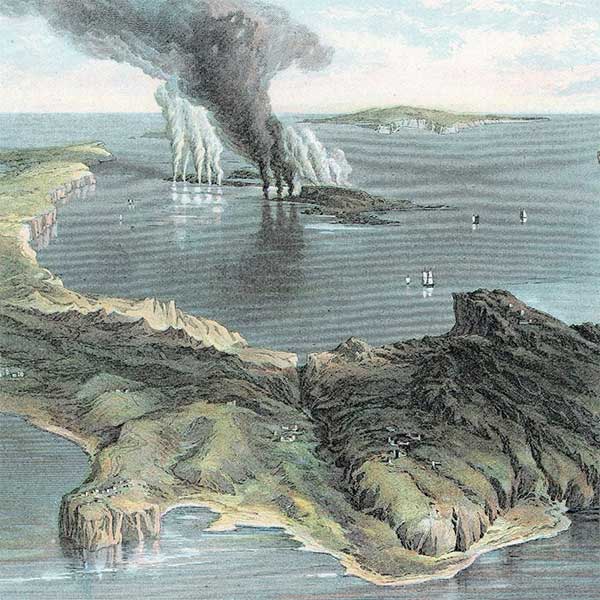

A painting depicting the volcanic island of Thera (Santorini, Greece) during the eruption. (Photo National Geographic).

The “super colossal” eruption of Thera, rated 7 (out of 8) on the volcanic explosivity index, is considered one of the most destructive lava eruptions in human history, likened to the explosion of millions of atomic bombs that flattened Hiroshima.

Many scholars believe that the painful memory of the volcanic disaster that occurred during the Bronze Age (around 1600 BC) may be reflected in Plato’s allegorical story of the sunken city of Atlantis, written over a thousand years later, and the horrific impact of this event is also recorded in the chapter “10 Plagues” in the Bible.

Although there are no direct records documenting the volcanic eruption or the massive tsunami, researchers have now found ways to determine the extent and impact of these events on life in the Mediterranean at that time – notably for Minos, a magnificent civilization in Greece that collapsed around the same time, in the 15th century BC.

Beverly Goodman-Tchernov examining a layer of ash at a Bronze Age site in Çeşme-Bağlararası, Turkey. (Photo National Geographic).

Unveiling a “Great Disaster” Tsunami

The paper states that the research was conducted at the archaeological site of Çesme-Bağlararası, located in the popular resort town of Çesme on Turkey’s Aegean coast, more than 100 miles northeast of the “paradise” Santorini. Investigations began in 2002 after ancient pottery was discovered during the construction of an apartment building.

Since 2009, archaeologist Vasıf Şahoğlu from Ankara University in Turkey has taken charge of excavations in the area, which has been almost continuously inhabited from the 3rd millennium to the 13th century BC.

He discovered collapsed city walls, layers of ash, and fragments of pottery, bones, and shells. Şahoğlu quickly reached out to colleagues from various fields, including Beverly Goodman-Tchernov, a marine geological sciences professor at the University of Haifa in Israel and a National Geographic explorer with expertise in identifying tsunamis in archaeology and geology.

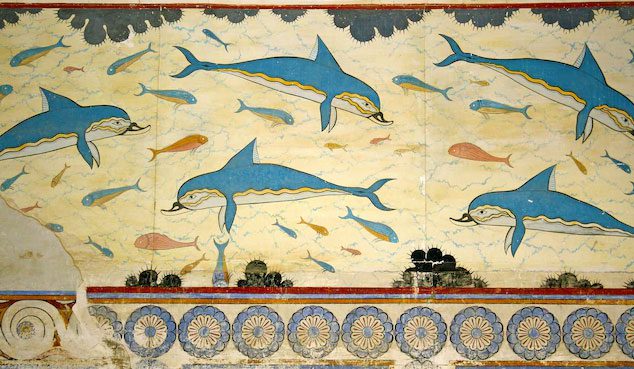

A Minoan fresco from the palace at Knossos, Crete, showing how the Thera disaster disrupted trade routes and infrastructure for the Minoans. (Photo National Geographic).

“The tsunami was primarily erosive… and not capable of depositing material, so we are very excited to find these artifacts,” Floyd McCoy, a geology and oceanography professor at the University of Hawaii, Windward Community College, expressed in an email.

McCoy has studied the volcanic eruption and tsunami at Thera but did not participate in the recent project, calling this research “a truly significant contribution, not only extremely useful for tsunami sediment research but also greatly meaningful in understanding the lava eruption at Thera.”

A Disaster Without Casualties?

One of the greatest mysteries of the Thera volcanic eruption is the remarkably low number of recorded victims: over 35,000 people are estimated to have died in the tsunami caused by the Krakatoa eruption. However, so far, only one body has been identified as “likely” a victim of the natural disaster: a man found buried beneath the rubble on the Santorini archipelago during investigations in the late 19th century.

Various hypotheses have been proposed: smaller volcanic eruptions that occurred earlier may have prompted people to flee the area before the historic double disaster; victims may have been incinerated by the superheated lava; drowned at sea; or buried in unmarked mass graves.

Map of where Thera – now Santorini is located. (Photo National Geographic).

“How could one of the worst natural disasters in history not claim a single life?” Şahoğlu wondered.

Professor Goodman-Tchernov suggested that researchers might not have recognized the sediments from past tsunamis, and it is also possible they found victims of the Thera disaster but “overlooked” or “failed to connect” the clues together.

However, at Çesme-Bağlararası, researchers reported that they have found the first victim of the catastrophic event: the remains of a young, healthy man with signs of trauma from a forceful impact, found lying amidst the debris of the tsunami. The skeleton of a dog was also discovered nearby at the same time.

Forensic examination and dating analysis of the two recently found skeletons will begin next month.

Artifacts remaining from one of the most horrific disasters in human history. (Photo National Geographic).

The “Furious” Waves

Researchers have determined that four tsunami waves struck Çesme-Bağlararası over a period of days to weeks. This “is particularly intriguing” to McCoy because he had previously indicated that there were four phases leading up to the Thera volcanic eruption. Researchers have long questioned: “Which phase of the eruption triggered such a devastating tsunami?

As the water receded between the tsunami waves, it appears that the surviving residents took the opportunity to search for victims amidst the chaos. A depression was found just above the body of the young man – a sign that someone had “grasped” or “clutched” him with a strong pull. However, that person stopped too soon to save the victim.

Evidence of the search for victims during this tsunami indicates a concern for burying the bodies of the unfortunate victims after the disaster, possibly in mass graves to mitigate the spread of disease afterward, helping to explain the general absence of human victims from the destruction levels in the Aegean.

The Journey to Truth is Not Over

According to historical records, the Thera volcanic eruption is set in a timeframe known as Late Minoan IA, associated with the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt in the 1500s BC. However, radiocarbon dating on wood fragments found in the ash layer at Akrotiri dates to the late 1600s BC — a discrepancy of over a century.

While scientists continue to debate the timing of the Thera disaster and the damage it caused to the Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, researchers hope this discovery will prompt archaeologists involved in the project to re-examine any “elusive” evidence of one of the most catastrophic natural disasters in human history.

In the meantime, Şahoğlu hopes that this archaeological site – located in the heart of a famous resort town, may one day become a tourist attraction.

Jessica Pilarczyk, an assistant professor of earth sciences and head of research on natural hazards at Simon Fraser University, stated that humanity will face not only the hazards that still smolder offshore from the past but also potential disasters that may occur in the future. She added that this research is a hope to raise awareness and even a spirit of preparedness among the public regarding natural hazards.

“Just because disasters like tsunamis occur infrequently and far apart, sometimes centuries pass before another devastating event happens, does not mean people can assume they are safe.”