Warhorses: Indispensable Companions of Ancient Emperors and Generals

Beside their masters, these horses were not just mounts; they were key players in achieving legendary victories and even shaping the world. Below are four horses honored by ancient historians.

Bucephalus of Alexander

Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BC, Kingdom of Macedon) is one of the greatest conquerors in human history. His warrior career began in his teenage years and continued until his death, resulting in the conquest of nearly the entire known world. Thanks to him, the borders of Greece extended all the way to Punjab, India.

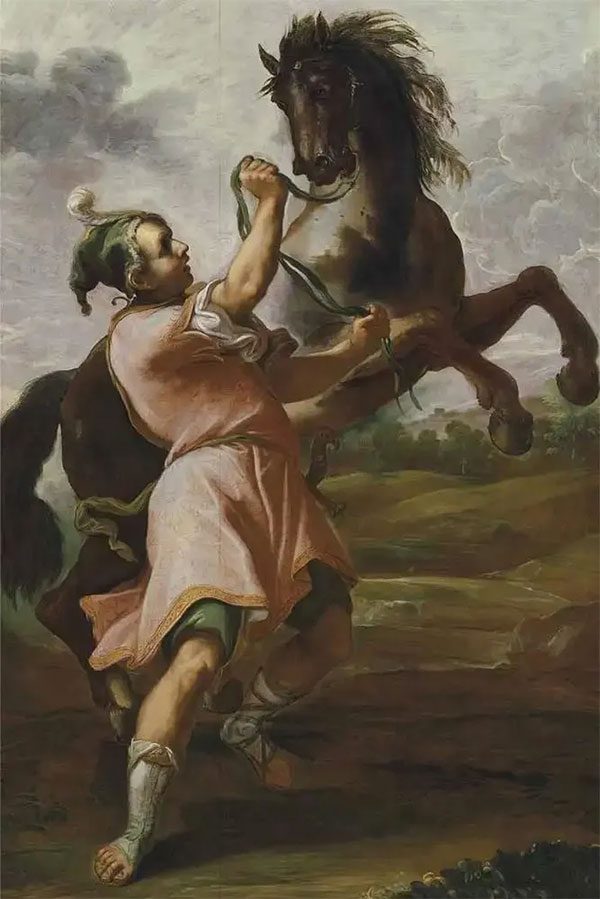

Alexander and Bucephalus, painting by Domenico Maria Canuti (1645 – 1684). (Image: Thecollector.com).

Alongside Alexander the Great was Bucephalus, a horse described by historian Plutarch (46 – 119 AD) as “a reflection of the Great Emperor.” Born on the same day as Alexander, the moment it met its master was the turning point in the flow of history.

Initially, Bucephalus was purchased by Philip II, Alexander’s father. Despite being a young horse, Bucephalus was incredibly stubborn and would not allow anyone to ride him.

After several failed attempts, Philip II angrily decided to get rid of the horse. Alexander, appreciating its beautiful appearance, begged his father for permission to tame it himself. Although he had no experience with horses, Alexander quickly realized that

Bucephalus was frightened by its own shadow and successfully calmed it down. From that moment on, Bucephalus and Alexander were inseparable. When Alexander began his campaign to invade Persia, Bucephalus was chosen as his war steed.

In the role of a warhorse for the general and later Emperor Alexander, Bucephalus was present on every battlefield. It showed bravery and resilience just like its master, never faltering even when injured. After many battles, both Bucephalus and Alexander were scarred but had reached what was then called “the edge of the world” – India.

In 326 BC, after the Battle of Hydaspes, Bucephalus died at the age of 30. Alexander was heartbroken over Bucephalus’s death. The emperor founded a city on the banks of the Hydaspes River and named it Alexandria Bucephala. Three years later, he also passed away in Babylon, leaving behind a vast empire.

Caesar’s Unique Horse

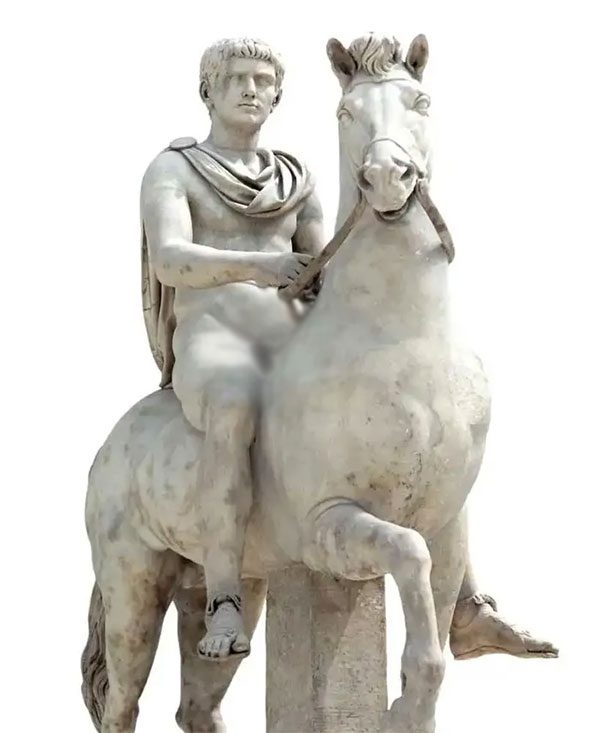

Julius Caesar riding across the Rubicon, painting by Adolphe Yvon (1817 – 1893). (Image: Thecollector.com).

Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) was a renowned general, politician, and dictator. His warhorse, although unnamed, was just as famous as Bucephalus.

According to historian Suetonius (69 – 122 AD), this horse had a unique congenital defect with split hooves that looked “almost like human feet.” Since its birth, soothsayers predicted that whoever rode it would become the ruler of the world.

Caesar cherished the “multi-toed horse” for two reasons: its unique hooves and the fact that only he could ride it. On its back, Caesar crossed the Rubicon, extinguishing the flames of civil war.

Whenever faced with uncertain odds of victory, he urged the “multi-toed horse” to the forefront to boost the morale of his troops. When the “multi-toed horse” passed away, Caesar had a statue made in its honor and placed it before the Temple of Venus Genetrix, the mythical ancestor of his family.

Incitatus of Caligula

Emperor Caligula and Incitatus, who was almost made a senator. (Image: Thecollector.com).

Caligula (12 – 41 AD, Rome) was the third emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the first dynasty of Rome. His reign was relatively short but closely associated with the horse that almost received a senatorial title – Incitatus.

Unlike the warhorses of Alexander and Caesar, which spent most of their lives on battlefields, Incitatus rarely saw combat. Emperor Caligula treated it like a pet, building a lavish stable for it, akin to the finest home, with marble walls and a feed trough made of ivory. According to historian Cassius Dio (155 – 235 AD), each day, Caligula’s servants would bring oats mixed with gold flakes for Incitatus to eat.

One day, Emperor Caligula unexpectedly demanded to appoint Incitatus as consul, the highest office in the Julio-Claudian court. This caused astonishment and fierce opposition among the senators, leading to Incitatus’s failure to achieve the position.

However, after its death, Incitatus became a prominent character in stories about Caligula. Supporters of the emperor believed he suggested giving the position to Incitatus as a warning to the senators. Detractors thought the emperor was a tyrant so mad that he would consider appointing a horse as consul.

Borysthenes from Alan of Hadrian

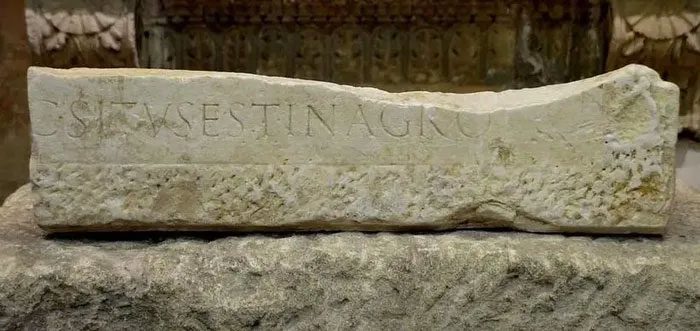

The remaining fragment of the monument inscription for Borysthenes from Alan. (Image: Thecollector.com)

Emperor Hadrian (76 – 138 AD, Rome) spent much of his life surveying his territories. He often traveled to visit the lands under his rule, eating and sleeping in his battle gear alongside his soldiers. Naturally, the emperor needed a suitable means of transport for his continuous travels, which was a horse named Borysthenes from Alan.

Borysthenes from Alan was of Alan origin and was a gift from King Rasparaganus of the neighboring Roxolani as a token of gratitude to Emperor Hadrian. True to its name Borysthenes (swift), it was extremely lively and agile.

In addition to his official duties, the emperor frequently rode Borysthenes from Alan for hunting. During one hunting expedition, the horse tragically died. Grieved, the emperor held a very solemn funeral for it, followed by constructing an extravagant tomb.

On the tomb of Borysthenes from Alan, Emperor Hadrian had inscribed a lasting tribute to the horse in literal terms: “This is Borysthenes from Alan, the fastest horse ever to gallop on water, crossing marshes and the Tuscan hills – no wild boar it pursued dared to bite back with its white teeth – spitting water far out to the tip of its tail, youthful, with all limbs intact, now lies here in this field.”