While biological warfare is strictly prohibited under international conventions and laws today, it was once regarded as a clever tactic in the past.

In the pursuit of victory, adversaries did not hesitate to unleash everything from venomous “animal bombs” to the corpses of individuals deceased from the plague upon their enemies.

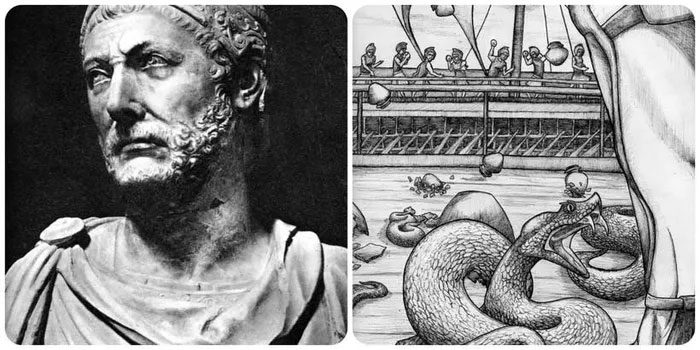

Venomous Snakes

In 184 BCE, Hannibal, the general of Carthage (247 – 183), faced off against Emperor Eumenes II (221 – 159) of Turkey in a naval battle. Known for his lack of naval strength, Hannibal was expected to lose.

Unexpectedly, this military genius devised a brilliant strategy to turn the tide by utilizing venomous snakes. He ordered his soldiers to capture as many highly poisonous snakes as possible, place them in clay jars, and throw these jars onto the enemy’s ships.

Hannibal’s clever use of clay jars containing venomous snakes led to his victory. (Photo: Thecollector.com – Khqa.com)

Initially, Emperor Eumenes II laughed upon seeing the clay jars, believing they posed no lethal threat. However, it wasn’t long before fear gripped him. The rattled venomous snakes became incredibly aggressive, biting anyone they encountered, causing panic among his soldiers who fled in terror. Reluctantly, the emperor ordered a retreat. Hannibal of Carthage emerged victorious without losing a single soldier.

Interestingly, Hannibal was not the only one to exploit venomous animals. In 198 CE, in Arabia, soldiers of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE – 224 CE) adopted this tactic as well.

They captured numerous scorpions, placed them in clay jars, and then hurled them at the army of Emperor Septimius Severus (145 – 211) of Rome. Terrified, the Roman soldiers scattered, breaking formation and forcing Severus to temporarily withdraw.

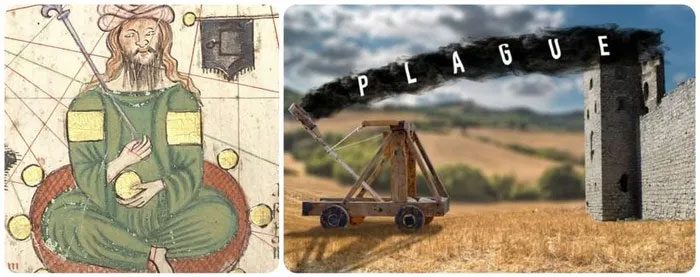

Corpses of Plague Victims

Throughout human history, the plague has always been the most horrifying nightmare. However, while many nations and regions were paralyzed by it, Grand Khan Jani Beg (? – 1357, Mongolia) perceived this disease as a supreme weapon.

Jani Beg’s strategy of launching “black death” at the walls of his enemies was akin to mutual destruction. (Photo: Thecollector.com – Khqa.com)

In the 1340s, after three years of unsuccessful siege at Caffa on the Crimean Peninsula, he ordered his soldiers to use catapults to hurl the corpses of those who died from the plague into the city.

“Mountains of dead bodies were thrown in, and those inside the city had no idea where to run or hide to avoid the risk of infection. Soon, the decaying corpses polluted the air and poisoned the water supply,” wrote historian Gabriele de’Mussi (1280 – 1356).

Despite employing this abhorrent tactic, Grand Khan Jani Beg did not achieve victory. The “black death” not only attacked the enemy but also devastated his own troops, resulting in a situation of “mutual destruction.”

The consequences of exploiting the “black death” extended beyond the devastation of Caffa, as many sailors in the city abandoned it and fled to Genoa, Messina, and Constantinople. They carried the plague throughout Europe, ultimately leading to a pandemic.

Smallpox and Malaria

In the 18th to 19th centuries, British colonizers invaded America and faced fierce resistance from Native Americans. In an effort to win without exerting much effort, they deliberately took blankets from those infected with smallpox and gifted them to local tribes to spread the disease and kill as many people as possible.

The British accused of causing a smallpox disaster for Native Americans. (Photo: Thecollector.com – Khqa.com).

Although the British never admitted to this crime, military diary entries from William Trent (1715 – 1787) indicate that they provided two blankets and a handkerchief from a smallpox hospital to the Native Americans.

In addition to Trent’s records, there are many other documents detailing the conspiracy to murder Native Americans by infecting them with smallpox. “I pretended to bend down to slip them a few blankets, of course being careful not to infect myself,” Captain Simeon Ecuyer, commander of Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh), told others.

During the same period, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821) engaged in similar tactics. In the summer of 1809, during a conflict with British forces occupying Walcheren, an island off the mouth of the Scheldt, he ordered soldiers suffering from malaria to spread the disease as widely as possible.

Within a month, nearly 10,000 British soldiers fell ill. The British had no choice but to abandon Walcheren.

Mustard Gas

Gas mask ineffective against mustard gas. (Photo: Thecollector.com – Khqa.com)

World War I (1914 – 1918) marked the era of diverse biological weapons, with mustard gas being one of the most terrifying. True to its name, it emitted a pungent smell reminiscent of mustard.

The first use of mustard gas occurred in July 1917 in Ypres, Belgium. Soldiers reported seeing a “shimmering cloud” surrounding their legs. Wearing gas masks, no one paid attention to this “cloud.” Little did they know, mustard gas could be absorbed not only through the respiratory system but also through the skin. It caused the skin to become red, blistered, and excruciatingly painful.

Mustard gas does not dissolve easily in water, making it impossible to wash off effectively. When inhaled into the lungs, it caused lesions on the lung membranes. If it entered the eyes, mustard gas could damage the cornea, leading to blindness.

The more humid the environment, the faster mustard gas acted due to hydrolysis. Terrifyingly, this toxic gas did not kill its victims immediately; instead, it caused their bodies to fester, resulting in immense suffering and prolonging the wait for death for up to six weeks. In Ypres alone, mustard gas inflicted “slow death” on 10,000 people.