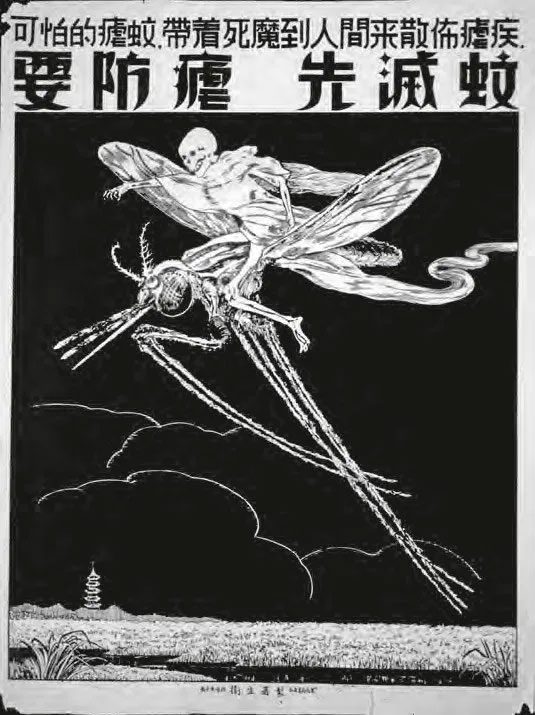

Mosquitoes are hosts that transmit deadly infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, and yellow fever…

Today, these diseases are treatable, and vaccines for malaria and dengue fever are available. However, a few decades ago, contracting malaria or dengue fever was akin to holding a death sentence. In the early 2000s, mosquitoes were responsible for an average of 2 million deaths per year. While this number is gradually decreasing, approximately 725,000 people still die each year from mosquito-borne diseases.

Due to the dangers posed by mosquitoes, Nobel Prize-winning scientist in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 (for his research on hepatitis B antigens), Dr. Baruch Blumberg (born in 1925), estimated through extrapolation that mosquitoes have caused the deaths of half of the total human population, among the 108-109 billion people who have ever existed on Earth over the past 192,000 years, primarily due to malaria.

Female mosquitoes suck blood and simultaneously inject parasites into the victim’s body.

Today, there are approximately 100 trillion mosquitoes flying around the globe, with the exception of a few small islands, Iceland, and Antarctica, where mosquitoes are absent. Female mosquitoes bite and suck the blood of warm-blooded animals, including humans, to survive, grow, and lay eggs.

Female mosquitoes both suck blood and inject parasites into their victims, causing dangerous and deadly diseases.

Here are five significant turning points in human history associated with diseases caused by mosquitoes.

1. Mosquitoes Contributed to the Liberation of the United States

The Anopheles mosquito, which transmits malaria, played a role in the success of General George Washington. In the fall of 1780, General Charles Cornwallis, leading the British Empire’s army, received reports that his troops were suffering from malaria and were no longer able to fight.

In the spring of 1781, he had to pull his sick army back toward Virginia to avoid the lingering threat of malaria that had been plaguing them for nearly six months. In August 1781, the British retreated to Yorktown, a marshy area along the banks of the James River and the York River, which coincided with the peak season for Anopheles mosquitoes.

The malaria-transmitting mosquito contributed to General George Washington’s success.

On September 28, when he surrounded Yorktown, Washington commanded 8,700 healthy soldiers. By October 19, when Cornwallis surrendered, only 3,200 soldiers were still fit to fight; two-thirds were incapacitated by malaria. Cornwallis admitted that he did not lose due to being defeated by Washington, but because he surrendered to the Anopheles mosquitoes.

Famous historian J.R. McNeill hailed the Anopheles mosquito as one of the little mothers that gave birth to the United States of America.

2. Mosquitoes Helped Britain Colonize Australia

Many years before the 13 American colonies declared their independence, the British Empire sent about 2,000 prisoners to America each year, totaling approximately 60,000 prisoners. This was done to alleviate the burden of criminals that needed to be held in Britain.

After the United States gained independence, Britain shifted its focus to sending prisoners to Africa, including the Gambia colony, but 80% of prisoners died within just a year of arriving in Africa due to malaria. After realizing that Australia was free from such diseases, in January 1788, Britain landed in Botany Bay (present-day Sydney) to begin their colonization of Australia.

3. Mosquitoes Aided Europe’s Colonial Expansion

In the 17th century, through trade with the Americas and Africa, European nations acquired a folk remedy for malaria, derived from the bark of the cinchona tree in South America, known as quinine powder.

European colonizers, having been exposed to diseases for an extended period, developed stronger immune systems. When they invaded colonies, they spread diseases to the indigenous people, using these very diseases to decimate them.

Malaria, yellow fever, and dengue fever traveled with European colonizers and their slaves, some individuals developing natural immunity against these diseases. Upon arriving in the Americas, these diseases quickly found the Anopheles mosquito as their host due to their “complete compatibility.”

Together with tuberculosis and smallpox, the aforementioned fevers and mosquitoes spread throughout North America, helping colonizers “wipe out” the indigenous Native Americans and expand European colonial presence after Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas.

It is estimated that in 1492, the year Columbus discovered the Americas, the population of the Western Hemisphere was around 100 million indigenous people. By 1800, only 5 million remained. This means that over the span of 300 years, hundreds of millions of indigenous people died due to infectious diseases.

4. Mosquitoes and the Fall of the Roman Empire

According to a Roman scholar, the Pontine Marshes, covering 310 square miles around Rome, served as a stronghold for this ancient empire. He stated that before entering this area, people had to cover their necks and faces carefully to prevent mosquito bites.

During the Roman Empire, malaria was a long-standing and deadly enemy, according to historian Kyle Harper. Malaria weakened the vitality and depleted the labor force of the Roman populace, contributing to the empire’s decline.

The Pontine Marshes in 1850.

Before World War II, Italian leader Benito Mussolini attempted to drain the Pontine Marshes to eradicate mosquitoes. When World War II broke out, the Italian fascists flooded this marshland again to “breed mosquitoes” to hinder the advance of Allied forces at Anzio.

5. Mosquitoes Slowed the Economic Development of the South

Sima Qian, a Chinese historian from the early Han Dynasty, wrote that the area south of the Yangtze River was marshy and humid, and men often died young. At that time, before men traveled south, they would allow their wives to remarry if they died on the journey.

Malaria hinders the wealth and prosperity of society.

Like malaria, dengue fever has plagued East Asia for thousands of years, and historian William H. McNeill suggests that this disease may have also slowed the southward expansion of ancient China.

In Italy and Spain, there existed a “Southern Problem,” where malaria and yellow fever were also present, leading to uneven economic development between the southern and northern regions.

Malaria undermines productivity, slows individuals down, and dulls the personality of patients. Malaria hinders the wealth and prosperity of society, as noted by an Italian politician in the early 20th century.