-

Construction Period: 1463 – 1853

-

Location: Istanbul, Turkey

In 1453, when Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II conquered Constantinople (later known as Istanbul), the city was in ruins, and the population had fled. A magnificent palace was constructed to serve as a government institution, but it was not suitable until the people returned and rebuilt the city. It was only in 1472 that Istanbul became the capital of his empire, and Topkapi Palace (translated as “Palace of the Cannon Gate,” a name used in the 19th century) began to function as an administrative center and royal residence. The site is located on a hill with stunning views of the Bosporus Strait, the Golden Horn, and the Sea of Marmara.

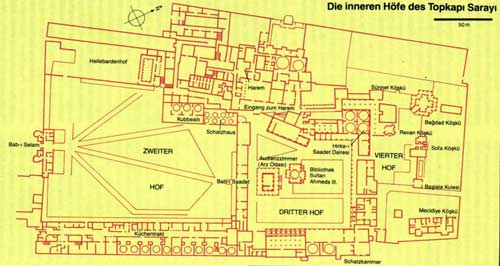

Palace plan (Photo: atillakaban)

Referring to Topkapi as a “palace” might evoke misleading associations for contemporary readers, suggesting a unified architectural structure akin to the Palace of Versailles, aimed at impressing with its scale and grandeur. In the 15th century, there was no palace that held this significance. The royal residence and government institution were a collection of buildings that gradually formed as needs arose.

The decoration at Topkapi follows the highest order of opulence; this consistent level of luxury and the fact that many of its structures remain largely intact create a unique character—an enduring symbol of one of the most powerful dynasties in the world. Topkapi Palace retains an aura of wealth, sophistication, and an enchanting charm that is unmatched anywhere else.

First Courtyard

The First Courtyard, with its entrance facing west, is closest to the city and features the largest and most famous gate. Once overshadowed by the 6th-century Byzantine church of Hagia Irene, which the Ottomans utilized as a weapon workshop and a large infirmary where boys could escape the harsh discipline of the monastery school. There was also a mint and large warehouses for transporting bulky goods, including 500 loads of timber each year.

The welcoming gate decorated with prison towers by Murat III in the 1570s (Photo: rcip.com)

Entering the courtyard through the Imperial Gate, one would see the heads of traitors displayed like at London Bridge. The gate still stands impressively, a medieval structure. The original gate became the Welcoming Gate with prison towers decorated by Murat III in the 1570s. Here, everyone except the Sultan was required to dismount and enter on foot.

There is absolute silence upon entering the palace, aside from the officials bearing the scepter; visitors are observed by many short and mute attendants who can read and write. Only a single important envoy could visit with a full entourage, such as William Harborne, the first English ambassador. In the 16th century, Francis I of France forgot to pay Pierre Gyllius for sending him to purchase Greek manuscripts and allowed Pierre to join the elite Janissary Corps.

|

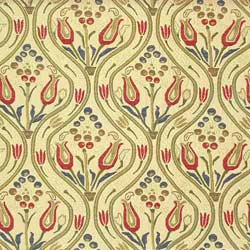

| Ornamentation on one of the sparkling Iznik tile panels (Photo: voyagedecoration) |

Some details recorded by Pierre include the dismantling of the ceramic tiles of the inner gate. Alvise Gritti from Venice became a close friend of Suleiman the Magnificent, who visited Suleiman at his residence in Pera, but was unable to receive a reciprocal visit to show hospitality. There was also a Hassan, a poor prisoner from Lowestoft, England, who was happy to be castrated and then became wealthy as a teacher at the university where all the professors were castrated whites. He was favored and became a valuable friend to English merchants, understanding that the more scandalous the tales, the greater the reward received.

Second Courtyard

The Second Courtyard, or the Imperial Council Hall, remains a lawn with a few perennial trees, surrounded by a wall to keep gazelles from wandering into the area. Behind a long, flat area that serves as the kitchen today is the ceramics museum, with several quarters for chefs and assistants, along with extended warehouses. Opposite is the Imperial Council Hall, dating from the early 16th century, redecorated in the 19th century and during the Republic. Next door are the barracks for the Janissaries that Davut Agha rebuilt in the late 16th century, with only one such barrack remaining today.

Between the soldiers’ barracks and the Imperial Council Hall stands a tower, from which the Sultan could overlook the palace. The classical peak of the tower was added in the mid-19th century, possibly by the Swiss architects Fossati, who also worked in St. Petersburg. Outside the Imperial Council Hall is one of the other original structures of Mehmet—a massive stone hall of the Outer Treasury, followed by the Gate of Felicity in Baroque style.

In the Imperial Council Hall, one can envision important figures in the palace, dressed in kaftans beautifully embroidered, sitting under a dome with gleaming columns adorned with gilded caps. As many as 600 witnesses and volunteers stand outside drawing water from the fountain. This detail provides some insight into the glorious period of the Imperial Council Hall.

Third Courtyard

|

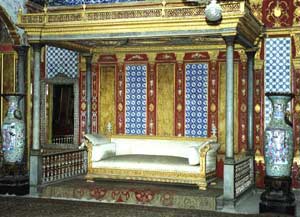

| The Grand Hall of the Throne, in the Harem, is an airy space used for official meetings, built for Murat II in 1588 (Photo: traveling.igw) |

Through the Gate of Felicity, one faces the Audience Chamber, built by Ala’ettin Agha, the court architect, between 1515 and 1529. He took on many modernization programs initiated by Suleiman, partly as a result of a severe earthquake in 1508. Surrounding the Audience Chamber are magnificent porticos, with special Iznik tile panels by the entrance and a charming fountain named after Suleiman. Inside, the walls and floors were covered with a layer of golden fabric inlaid with pearls. However, all of this was diminished due to the economic crisis in the 18th century. To the left of the water pavilion is the mosque of the university, now the palace library angled towards the holy city of Mecca.

All three courtyards are surrounded by the university’s dormitory rooms: the first two sides were destroyed by fire in 1857, while the other sides are replicas but adjoin the original walls and form a museum for costumes, art, and for the administration of the palace. The best students upon graduation would attend a general meeting with the Sultan, with positions such as Sword Bearer or Horse Keeper still vacant. The halls are based on other original constructions, now serving as storage for the treasures of the Prophet Muhammad brought back by Selim I after he conquered Egypt. There is a very wide entrance hall with tiled roofs and a large fountain designed by Davut Agha for Murat III. The former bedroom can only be glimpsed as it is now a storage for the flags and cloaks of the Prophet. The walls feature the most beautiful Iznik tile panels from the 16th century. Across, overlooking the Sea of Marmara, are the rooms used for daytime rest by Mehmet II, a series of splendid rooms topped with a tower and an open fountain. Today, these details form the Treasure Museum.

Harem

Entering the Harem through the Eunuch Courtyard, one passes through towering soldiers’ barracks. Guarded by black eunuchs, the Harem was the residence of the Sultan’s wives, concubines, and female relatives, many of whom held real power. It is not grand in scale, even the Valide Sultan’s hall. The 18th-century tiles are not rich in color but impressive in design, with a complete row of Rococo rooms added at the end of the 18th century, featuring mirrors and many brightly colored paintings depicting rural scenes, possessing their own life. The most beautiful room is that of Murat III, which has a fountain, but the windows are locked due to the expansion by Ahmed I. Below is a very large pool designated for the Harem. The Grand Hall of the Throne is possibly a work of Davut, but it has suffered damage due to changes in shape. The Succession Pavilion is very beautiful, consisting of the only remaining original dome from the early 17th century, intricately decorated with gilded borders and floral motifs.

Official palace of the Sultan (Photo: islamicarchitecture)

Fourth Courtyard

The terraced plain of the Fourth Courtyard features two of the most beautiful kiosks in the palace – likely the work of Hasan Agha – commemorating the victory of Murat IV. The Baghdad Kiosk is the largest, adorned with beautiful ceramic tiles and intricate wood inlay work. On either side of the tall, covered fireplace are columns clad in glimmering tiles, echoing the tiled columns at the opposite end of the terraced plain. There is also a balcony that juts out with a water basin, where the Sultan could relax nearby. The charm of personal life is encapsulated here with the lovely domed roofs and classical proportions. Most of the pavilions in the park are no longer standing, including the Pearl Kiosk. It was here that Dallam came to practice playing the organ, a gift from Elizabeth I of England.

In a way, these gilded pavilions fashioned from marble and common stone are a miniature representation of Ottoman architecture, as well as the relationship between interior and exterior spaces. Topkapi Palace, known simply as Saray Mới when the Ottoman sultans resided here, carries a melancholic emptiness in its majestic offices that lingers behind.

Facts and Figures:

-

Total area: 700,000 m2

-

Second Courtyard: 160x130m

-

Wall length: 5km

-

Gates: 6 main gates

-

Population in 1640: Estimated at 40,000 people.