Excavating a tomb in Jiangxi Province, Chinese archaeologists were astounded to find the remains of 46 young women in a state of undress.

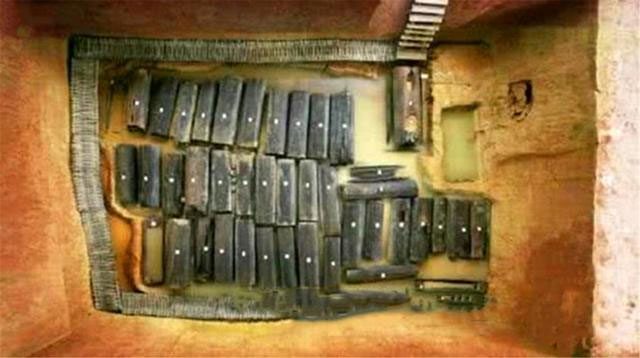

Strangely, these 46 coffins were identical in shape and size.

The coffins in the over 2,000-year-old tomb.

According to Sohu, the tomb, dating back approximately 2,000 years, was discovered by a local resident in Jing’an County, Jiangxi Province, China, in 2007.

Local residents reported the find to authorities, and archaeologists quickly flocked to the site. Upon excavation, they were surprised to find 46 coffins surrounding a central coffin.

The central coffin was identified as that of the tomb’s owner, distinguished by its size and the use of rare wood materials.

Except for the owner’s coffin, all 46 other coffins contained the remains of young women buried in the nude, averaging around 20 years of age. Surrounding them were numerous objects related to sewing and weaving. Archaeologists discovered signs indicating that these women endured extreme suffering, having been poisoned and buried alive in their coffins. In contrast, the tomb’s owner appeared to have passed away peacefully.

The archaeologists noted that the remains were unusual as they were surrounded by crystals. These transparent crystals, resembling glass, emitted a greenish glow in the dark, with the largest measuring up to 8.5 cm in length. No expert present at the time had ever encountered such a bizarre phenomenon before.

The numbered coffins in the tomb.

The ancient tomb discovered may be the final resting place of King Zhang Wu, the ruler of the State of Chu, a small vassal state from the Xia to the Western Zhou period. Based on the number of remains found, burial methods, and the age of the young women, it can be inferred that they died according to the custom of ritual suicide.

To ensure that he would enter the afterlife dressed in fine clothing and living in luxury, King Zhang Wu ruthlessly ordered the imperial seamstresses to die with him. The concubines were forced to consume poisoned watermelon.

The glowing effect of the remains may be due to compounds that create luminescent crystals within the coffins, including Ferric phosphate (FePO4) and other unidentified fluorescent substances. After 2,500 years, these toxins may have transformed into luminescent materials by the time of discovery.

According to Sohu, the practice of burying nobles and royalty with living individuals was quite common in the history of feudal China, stemming from the belief that a person would transition to the world beyond after death.

In addition to being buried with wealth to continue enjoying prosperity in the afterlife, the deceased also required attendants.

Despite hypotheses being proposed, the luminous phenomenon of the remains discovered by archaeologists remains scientifically unexplained, thus retaining its mystery within the field of archaeology.

Sohu notes that the origins of this practice date back to the Shang Dynasty, with changes beginning in the Qin Dynasty. The tomb of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, was buried with a terracotta army.

This practice of burying living people continued until the time of Emperor Hongwu Zhu Yuanzhang and only completely ceased during the reign of Kangxi (1654-1722), the emperor of the Qing Dynasty. Kangxi strictly prohibited the use of living individuals for burial, after which Chinese historical records no longer documented any cases of living burial, according to Sohu.

- Why did the concubines buried with Qin Shi Huang not close their legs after being buried alive?

- The tomb buried 4 sets of children’s remains under 4 corners reveals cruel and inhumane burial customs

- The practice of ritual suicide: Concubines forced to drink poison, mercury poured on their bodies, and other barbaric methods before being buried alive with the king