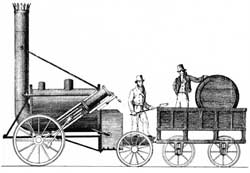

The first successful creator of a passenger train locomotive was George Stephenson, a miner from England. Before working in the mines, Stephenson became familiar with the steam engines of James Watt, and following the ideas of Murdock and Trevithick, he built a locomotive that could pull 90 tons over a distance of 85 miles. Stephenson later constructed a second and then a third locomotive, weighing 4.5 tons, with wheels measuring 1.42 meters in diameter. The third locomotive, named Rocket, was put into operation in 1830, marking the beginning of the railway industry. In initial trials, the Rocket carried 36 passengers and ran at a speed of 30 miles per hour.

The first successful creator of a passenger train locomotive was George Stephenson, a miner from England. Before working in the mines, Stephenson became familiar with the steam engines of James Watt, and following the ideas of Murdock and Trevithick, he built a locomotive that could pull 90 tons over a distance of 85 miles. Stephenson later constructed a second and then a third locomotive, weighing 4.5 tons, with wheels measuring 1.42 meters in diameter. The third locomotive, named Rocket, was put into operation in 1830, marking the beginning of the railway industry. In initial trials, the Rocket carried 36 passengers and ran at a speed of 30 miles per hour.

George Stephenson also built the first railway line, which was 32 kilometers (20 miles) long, connecting the towns of Stockton and Darlington in 1825, where steam trains operated on a regular schedule. A second railway line was established by Stephenson in 1830, spanning 48 kilometers (32 miles) and linking the cities of Liverpool and Manchester with regular passenger services using steam locomotives. Stephenson also proposed that all national railway lines adhere to the same standard gauge, which was 4 feet 8.5 inches (1.44 meters), equivalent to the wheelbase of horse-drawn carriages of that time. This gauge was later adopted by European countries and the United States.

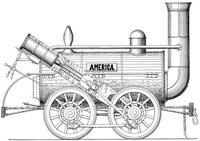

Thanks to the innovations of British inventors and the locomotives manufactured in England, the United States successfully developed its railway industry. Colonel John Stevens applied for a charter in New Jersey for railway operations. In 1825, Stevens built a locomotive and ran it in a small loop in Hoboken, New Jersey. He devised the principle of using geared wheels that engaged with the track’s toothed rail. Two years later, the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company in Pennsylvania decided to establish a railway line and imported two locomotives constructed by Stephenson. One of these locomotives, named Stourbridge Lion, was the first steam locomotive used commercially in the United States.

In 1831, the locomotive John Bull was brought to the United States to operate on the Camden and Amboy Railway, and thereafter the importation of British locomotives ceased because they were too heavy for the fragile railway lines in the U.S. Consequently, many new locomotives were produced domestically to be more suitable. Starting in 1830, Peter Cooper built the Tom Thumb locomotive for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and the West Point foundry produced the Best Friend locomotive for use in 1831 in South Carolina, along the route between Charleston and Hamburg.

The steam boilers were sometimes placed vertically, later modified to be horizontal. The historic locomotive De Witt Clinton, built by the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad at the West Point foundry, had a horizontal boiler. In August 1831, this historic locomotive pulled a train without a roof over a distance of 17 miles from Albany to Schenectady in 1 hour and 45 minutes, reaching a maximum speed of 30 miles per hour. On the return trip, the train traveled for about an hour. The De Witt Clinton locomotive was used for 14 years before being replaced by more advanced models.

The steam boilers were sometimes placed vertically, later modified to be horizontal. The historic locomotive De Witt Clinton, built by the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad at the West Point foundry, had a horizontal boiler. In August 1831, this historic locomotive pulled a train without a roof over a distance of 17 miles from Albany to Schenectady in 1 hour and 45 minutes, reaching a maximum speed of 30 miles per hour. On the return trip, the train traveled for about an hour. The De Witt Clinton locomotive was used for 14 years before being replaced by more advanced models.

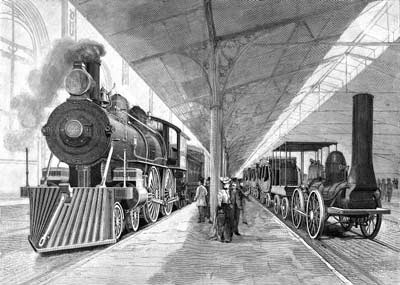

Due to its ability to carry heavy loads, railways became popular and widely utilized. The United States, rich in resources and vast in land, became an ideal place for pioneers in the railway industry. Railroads enabled the transportation of large quantities of materials from the frontier regions to factories. Consequently, Americans invested millions in establishing this mode of transport. The development of railroads in the mid-19th century marked a significant milestone in the advancement of a new industry. American inventors, with their mechanical ingenuity, made significant improvements to European locomotive designs. Within a few decades, railroads stretched across the desolate lands of the Mississippi River Valley, through fields to the Rocky Mountains, and all the way to the Pacific Coast.

To meet the growing demand for locomotives, specialized steel foundries emerged. In the early days, Mathew Baldwin’s foundry played a crucial role. Baldwin, previously a jeweler, switched careers and began producing a locomotive named Old Ironsides in 1832, modeled after the John Bull. This locomotive weighed 8 tons and could pull 80 tons of freight. Due to the steeper gradients and sharper curves of American tracks compared to those in England, manufacturers had to design locomotives with sufficient power while being easy to maneuver around curves. This aspect was later refined by engineer Jervis of the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, who also increased the number of wheels on the locomotive from 4 to 8.

At the Rogers Locomotive Works in Paterson, New Jersey, locomotives were produced with the cylinders located outside the frame. The locomotive built for the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad became a standard model for other locomotives in the United States for half a century. This locomotive featured 8 wheels and 11 cylinders measuring 45 cm in length. As locomotive power increased, engineers had to find ways to prevent wheel slip while the train was in motion. This slipping could be avoided by concentrating power on the driving wheels; thus, locomotives pulling freight cars had an increased number of driving wheels. Later, methods were sought to enhance locomotive power while using the same amount of coal, exemplified by the massive Virginian locomotive, measuring 32.6 meters in length and weighing 450 tons, capable of pulling 17,000 tons.

Passenger trains.

By 1850, most railway lines had been constructed in the states east of the Mississippi River. Rail networks radiated from major cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, connecting to cities in the Midwest and Southeast. In the Erie region, the railroad company opened a line from Piermont to Dunkirk in 1851, and by the 1880s, trains were running on routes from Chicago to the Mississippi River Valley. By 1857, both Chicago and St. Louis were significant transportation hubs.

In 1850, the U.S. House of Representatives began granting federal lands to companies building railroads, believing these routes would attract settlers to the undeveloped Midwest and South. With this land assistance, a railway line connected Chicago to Mobile, near the Gulf of Mexico in Alabama. Throughout the 1860s, railroads continued to expand and played a vital role in the American Civil War (1861-1865) by transporting troops and supplies to the front lines.

In the early 1860s, the U.S. government decided to develop a railway system across the continent. The proposed railroad would run along the 42nd parallel, from Omaha in Nebraska to Sacramento in California. Meanwhile, a railroad from Chicago would be constructed to connect to Omaha. In 1862, the U.S. Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act, assigning construction responsibilities to two companies: the Central Pacific Railroad, which would lay tracks eastward from Sacramento, and the Union Pacific Railroad, which would start from Omaha and head west. The U.S. government provided these companies with vast tracts of land and loans amounting to millions of dollars.

The railway from Sacramento began construction in 1863 and faced numerous challenges crossing the Rocky and Sierra Nevada mountains. To staff the railway construction, the Central Pacific Company hired thousands of Chinese immigrants, while other thousands from Europe worked for the Union Pacific Company. By May 10, 1869, the eastern and western railroads were connected at Promontory, Utah, making the United States the first country with a transcontinental railroad linking the East and West coasts. By the end of the 19th century, the United States had five transcontinental railroads, while the Canadian Pacific Railway completed its transcontinental route in 1885, connecting major cities like Montreal, Quebec, and Vancouver. Railroads opened new lands for settlement and commerce.

From a technical standpoint, after addressing the power of the locomotives, inventors turned their attention to making train travel safe and comfortable. To prevent accidents, engineers needed to devise an effective braking system. In 1869, George Westinghouse, in Schenectady, New York, patented a pneumatic brake system, allowing trains to stop more quickly than with manual brakes, resulting in a reduction in accidents. The safety of trains also relied on signals and the understanding of the positions of different trains. Initially, manual signals were used, but accidents continued to occur, leading to the consideration of automatic signals. These automatic signals first appeared in England in 1858 and were later adopted worldwide.

From a technical standpoint, after addressing the power of the locomotives, inventors turned their attention to making train travel safe and comfortable. To prevent accidents, engineers needed to devise an effective braking system. In 1869, George Westinghouse, in Schenectady, New York, patented a pneumatic brake system, allowing trains to stop more quickly than with manual brakes, resulting in a reduction in accidents. The safety of trains also relied on signals and the understanding of the positions of different trains. Initially, manual signals were used, but accidents continued to occur, leading to the consideration of automatic signals. These automatic signals first appeared in England in 1858 and were later adopted worldwide.

In 1873, American inventor Eli Janney patented the automatic car coupler, and in 1893, the United States Congress passed the Railroad Safety Appliance Act, mandating that all trains must be equipped with pneumatic brakes and automatic couplers.

Pullman Train Cars.

As the railroad industry expanded, it carried an increasing amount of cargo and passengers. Consequently, inventors sought ways to improve passenger cars. Initially, passenger cars lacked roofs, leaving travelers exposed to the elements and the soot and smoke from the locomotive. To address these inconveniences, enclosed cars were created, but improvements continued until cars featured air conditioning, reading lights, and adjustable seating.

Since trains operated day and night, passengers needed places to rest. In 1836, Cumberland Valley Railroad created sleeping cars, but at that time, these special cars were merely partitioned standard cars with uncomfortable beds. Passengers had no place to change clothes, and sanitation posed challenges. Later, mattresses were provided, but passengers had to make their own beds. It was in this context that George Pullman emerged.

After much consideration regarding passenger cars, Pullman successfully created a true sleeping car in 1858. He refurbished two old cars, established sleeping and washroom facilities, painted the interior a light red, upholstered the seats in plush fabric, illuminated the car with oil lamps, and added heating. The swinging upper berth and convertible chairs were significant contributions from Pullman.

To enhance the luxury of sleeping cars, larger cars were needed, which posed a challenge for railroad companies. Nevertheless, Pullman managed to build a sleeping car named Pioneer, valued at $20,000. This was a substantial investment for a single car. The Pioneer was used to transport President Lincoln’s remains from Chicago to Springfield. In 1867, George Pullman established a company dedicated to building sleeping cars called The Pullman Palace Car Company.

Pullman continued to design and manufacture sleeping cars, using six-wheel designs instead of four and enhancing the interiors with woven carpets, painted ceilings, decorative lamps, and all the furnishings of a luxury hotel. By 1867, George Pullman had 47 sleeping cars and was so busy that he could not produce more. Over the following years, several sleeping cars were exported to England, making this type of car popular there. By 1875, there were 700 Pullman cars operating on various rail lines. Today, the term Pullman is synonymous with train amenities.

Pullman continued to design and manufacture sleeping cars, using six-wheel designs instead of four and enhancing the interiors with woven carpets, painted ceilings, decorative lamps, and all the furnishings of a luxury hotel. By 1867, George Pullman had 47 sleeping cars and was so busy that he could not produce more. Over the following years, several sleeping cars were exported to England, making this type of car popular there. By 1875, there were 700 Pullman cars operating on various rail lines. Today, the term Pullman is synonymous with train amenities.

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, the U.S. government took control of the entire railroad system within its borders, returning it to private companies in March 1920.

For a century, steam power was utilized for rail vehicles. Technical advancements enhanced the power and speed of steam locomotives. By the late 19th century, many trains achieved maximum speeds of 50 miles per hour or 80 kilometers per hour. Engineers later sought to apply electricity to locomotives, and in 1895, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad tested an electric train over a distance of 3.5 miles or 5.6 kilometers in a tunnel under Baltimore. Gradually, electricity replaced steam power and was implemented in the rail systems of many countries. The use of electricity eliminated smoke and noise, both of which were inconvenient in densely populated areas. Electric power also provided essential strength for trains climbing steep grades, giving them significant acceleration.

For electric rail systems, the key challenge was ensuring a continuous power supply. In suburban areas, power was supplied via a third rail. On longer routes, two-way current was transmitted through overhead wires. One of the major electrification projects was the 440-mile rail line completed in 1915, running from the Rocky Mountains through Chicago, Milwaukee, and Saint Paul. A few years later, 42 powerful locomotives were used on these routes, each weighing 284 tons and powered by eight engines producing 420 horsepower, bringing the total power to 3,440 horsepower. Along with improvements in locomotives, iron rail tracks were replaced with steel tracks, a material that was 20 times more durable, while wooden cars were replaced with steel-clad cars by 1907.

After the invention of the diesel engine, this technology was applied to locomotives, and the first train using both electricity and diesel engines, named Burlington Zephyr, began regular passenger service in 1934. Other famous locomotives, such as the Union Pacific’s City of Salina, Santa Fe’s Super Chief, and the Comet serving New York City, New Haven, and Hartford, followed.

While new technologies were implemented in rail travel and routes expanded to remote areas, railroads faced competition from automobiles, buses, trucks, and airplanes. In the 1940s and 1950s, the replacement of worn-out train parts cost billions of dollars, leading to the bankruptcy of some companies. By the 1960s, railroad companies were still operating at a loss and required government assistance.

In 1970, the U.S. government established the Amtrak system to operate on routes connecting various cities, and the Railroad Reorganization Act of 1973 aided railroad companies in maintaining their services.

Rail Systems in Other Countries.

Rail Systems in Other Countries.

When railroads were constructed, new opportunities for settlement and commerce emerged. By the late 19th century, Argentina and Brazil experienced rapid growth following the completion of their rail lines. Railroads also crossed the Andes in South America, with Peru’s central railroad beginning construction in 1870.

Also in the late 19th century, England, France, and Germany installed railroads in their colonies across Africa and Asia. For instance, England contributed 25,000 miles of track to India, equivalent to 40,200 kilometers. Russia began constructing the Trans-Siberian Railroad, spanning 5,600 miles (9,910 kilometers), in 1891, completing it in 1916. Australia initiated the construction of a 1,108-mile (1,783-kilometer) railroad in 1912, which was completed in 1917, connecting Port Pirie to the city of Kalgoorlie. By 1949, China had 29,000 kilometers of railway, which increased to 54,000 kilometers by 1980, with an annual addition of 1,000 kilometers.

Japan also rapidly developed its rail system by the late 19th century. Since 1964, Japan has operated a high-speed train system connecting Tokyo and Osaka, and the Shinkansen has since become a symbol of Japan’s advanced technology and transportation.

The rail system that began in England has expanded throughout Europe. By 1870, most European countries had main rail lines, and engineers had drilled tunnels through the Alps to connect France with Italy and Switzerland via rail. By the late 19th century, the most famous passenger train in Europe, the Orient Express, began operating in 1883, linking Paris, France, with Istanbul, Turkey.

In the mid-19th century, France had six major railway companies established: Northern, Eastern, Western, Central, P.L.M (Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée), and P.O (Paris-Orléans). Later, the French government nationalized these railway companies in 1938 to form the National Railway Company S.N.C.F. (Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer). By early 1976, France began operating the high-speed train system known as TGV (train à grande vitesse) on the 425-kilometer route from Paris to Lyon, reducing travel time from 3 hours and 50 minutes to under 2 hours. By 1987, the TGV network expanded to cities such as Lille, Rouen, Marseille, Grenoble, Lausanne, Geneva, and Bern in Switzerland, and subsequently, this system was further developed to the northern, southern, and Atlantic regions of France.

In the mid-19th century, France had six major railway companies established: Northern, Eastern, Western, Central, P.L.M (Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée), and P.O (Paris-Orléans). Later, the French government nationalized these railway companies in 1938 to form the National Railway Company S.N.C.F. (Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer). By early 1976, France began operating the high-speed train system known as TGV (train à grande vitesse) on the 425-kilometer route from Paris to Lyon, reducing travel time from 3 hours and 50 minutes to under 2 hours. By 1987, the TGV network expanded to cities such as Lille, Rouen, Marseille, Grenoble, Lausanne, Geneva, and Bern in Switzerland, and subsequently, this system was further developed to the northern, southern, and Atlantic regions of France.

The railway system is a very fast mode of transportation that does not pollute the environment, is extremely safe, and is used not only for passengers but also for transporting hazardous materials such as explosives, compressed gases, and radioactive materials.