The Tuskegee Experiment is one of the most ethically abusive studies in United States history. The full name of the study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS), is “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male”, and it was carried out on a group of approximately 600 African American men suffering from syphilis.

On paper, this experiment involved X-rays, blood tests, autopsies, and spinal taps of the subjects, as researchers sought to gain a deeper understanding of the disease. However, the experiment would not provide treatment for syphilis but instead was designed to allow the progression of the disease to be monitored in the subjects.

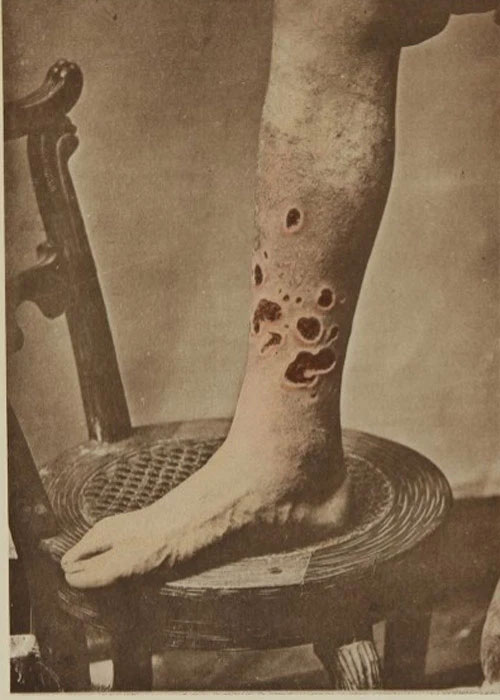

When the study began in 1932, syphilis was still an incurable disease. It spreads easily, starting with mild symptoms such as swelling near the groin. From there, the disease often progresses rapidly, leading to chronic fatigue, weight loss, hair loss, and even death.

To gain a better understanding of the disease, the Tuskegee Institute and USPHS decided to conduct a study in Macon County, Georgia. To entice applicants to participate in the experiment, they promised to provide free medical care to those involved.

Among the 600 selected African American men, 399 were afflicted with the disease, while the remaining 201 served as the control group for the study. The primary aim of the research was to understand the medical history of those infected and to observe the effects of untreated syphilis.

The experiment documented the progression of syphilis in the human body.

The study aimed to record the complete progression of the disease in each individual and its effects. However, the subjects of the study were unaware of the truth, and the promise of treatment was a lie.

Participants were never informed that the research was actually an experiment to better understand this sexually transmitted disease. Instead, they were told they would be treated to eliminate “bad blood” and receive free medical care. The subjects were informed that the treatment process would last six months and believed it would help cure them.

This deception was maintained throughout the early stages of the study, and by 1933, the Tuskegee researchers decided to extend the experiment for a longer duration. To continue pretending to provide treatment, they administered various ineffective medications to the patients to mislead the volunteers participating in the study.

Participants were not aware of the truth about the experiment.

However, patients began to suspect the treatments they were receiving, and many stopped participating in the experiments. To encourage patients and persuade them to continue in the study, volunteers were offered better meals as well as certain services and medications. At the height of the Great Depression—when economic hardship made it difficult to afford enough food and clothing—many found these offers too tempting to resist and returned to continue participating in the experiment.

Accordingly, Eunice Rivers, a nurse, was also hired by the USPHS to manage palliative care for the patients. The study organizers also began to cover funeral expenses for the patients, as this allowed them to conduct autopsies on the test subjects as part of the research.

Many patients began to doubt the treatments they were being provided.

In some cases, researchers refused treatment for the disease without the patients’ knowledge or consent. A list was even provided to physicians in Macon County in 1934 of patients who might seek their help, and the doctors were instructed to deny treatment, all in service of the research.

This continued for many years. In 1940, the Alabama Health Department was also provided with a list of patients and instructed not to treat them. In 1941, an initial medical examination discovered syphilis in some candidates who were supposedly healthy. These men were denied both participation in the experiment and treatment by the research team.

Gradually, the true motives behind the Tuskegee Experiment began to be revealed. Instead of observing and recording the effects of treatment, the researchers deceived the participants and monitored the uncontrolled progression of the disease in the bodies of individuals.

By 1947, penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis. This prompted the USPHS to open several Rapid Treatment Centers to treat those afflicted with syphilis using penicillin.

Many patients among them had symptoms that actually worsened.

However, the Tuskegee Experiment continued, and the 399 participants who could have easily been treated with penicillin were denied proper treatment. Many of these patients actually experienced worsening symptoms, yet they believed they had received safe treatment and began to transmit the disease to their partners.

After this secret was exposed, the federal government had to compensate the families of the patients. Specifically, they would receive medical care from the government for the rest of their lives.

When exposed, the federal government had to compensate the families of the patients.

Not until 1972 was the truth behind the Tuskegee Study finally revealed when Peter Buxtun disclosed information related to the study to the New York Times. On November 16, the article was published on the front page.

This ultimately brought an end to the Tuskegee Study. However, by the time the truth was revealed, only 74 participants in the study were still alive. 128 patients had died due to increasingly severe symptoms of syphilis or complications from the disease.

The revelation of the grotesque nature of the experiment led to public outrage, and a lawsuit was filed against the USPHS. The families of the subjects were compensated.

The Tuskegee Study is truly one of the most unethical studies ever conducted in history. Black men were targeted, manipulated, and then left to die while still believing they were receiving treatment. Advances in treatment, such as penicillin, were ignored to continue the research.