The TRAPPIST-1 system consists of 7 planets that offer an intriguing “time-travel” perspective on the history of our world.

TRAPPIST-1 is a cool dwarf star located 38.8 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius. It has 7 “child” planets, each resembling Earth in various aspects, with some even expected to harbor life.

A new study has taken a “journey back in time” to explore how these fascinating 7 planets came into existence.

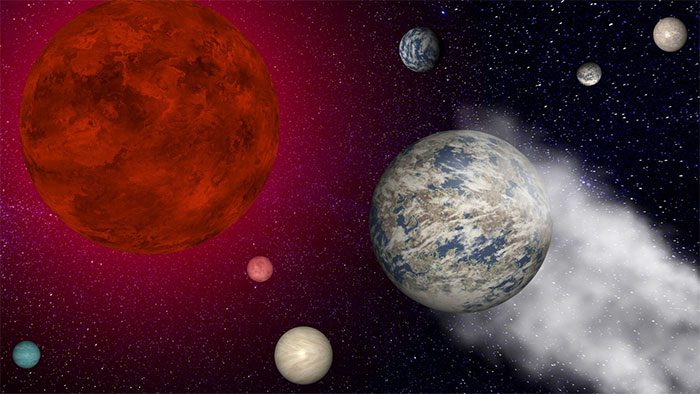

The red and cold TRAPPIST-1 star and its 7 orbiting planets – (Photo: NASA/Robert Lea)

Astronomer Gabriele Pichierri from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and colleagues have developed a model to explain the unique orbital configuration of the TRAPPIST-1 system.

Previously, pairs of neighboring planets in this star system were discovered to have orbital period ratios of 8:5, 5:3, 3:2, 3:2, 4:3, and 3:2. This rhythmic arrangement creates a harmonious “dance” as they “twirl” around their parent star, known as orbital resonance. However, there is a slight “offbeat”: TRAPPIST-1 b and TRAPPIST-1 c are in a 8:5 ratio, while TRAPPIST-1 c and TRAPPIST-1 d are in a 5:3 ratio. This discrepancy unintentionally reveals a complex history of planetary migration within the system.

According to the authors, most planetary systems are thought to have begun in states of orbital resonance but later experienced significant instability during their lifetimes, leading to the current “offbeat” state.

The model shows that the four inner planets of the system, located close to the parent star, evolved individually in a steady 3:2 resonance chain.

It was only when the inner boundary of the protoplanetary disk—existing around stars while they are still young and serving as the material disk for planet formation—expanded outward that their orbits loosened into the configuration we observe today.

The fourth planet, initially located at the inner boundary of the disk, moved further away and was then pushed inward again as the three outer planets formed during the second phase of the system’s formation.

This new discovery enhances our understanding of a process that occurred when the Solar System was still in its infancy, including the migration of Jupiter—the first-formed planet—that pushed and nudged the remaining forming planets.

Furthermore, these results indicate that the early Solar System was a far more chaotic world, with significant collisions pushing the eight planets into a tumultuous dance similar to what we see today.

The new study has just been published in the scientific journal Nature Astronomy.