New discoveries from dinosaur fossils indicate that millions of years ago in Canada, carnivorous dinosaurs hunted smaller herbivorous dinosaurs.

According to Reuters, scientists reported on December 8 the excavation of a fossil of a young Gorgosaurus—approximately 5 to 7 years old—measuring 4.5 meters in length. Notably, this fossil retains its stomach, preserving its last meal.

The Gorgosaurus belongs to the theropod dinosaur family, which includes the famous T. rex, existing a few million years later. Gorgosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur with short arms featuring two-fingered hands and a massive skull that measured 1 meter long. Its overall length reached 9 to 10 meters and it weighed between 2 to 3 tons.

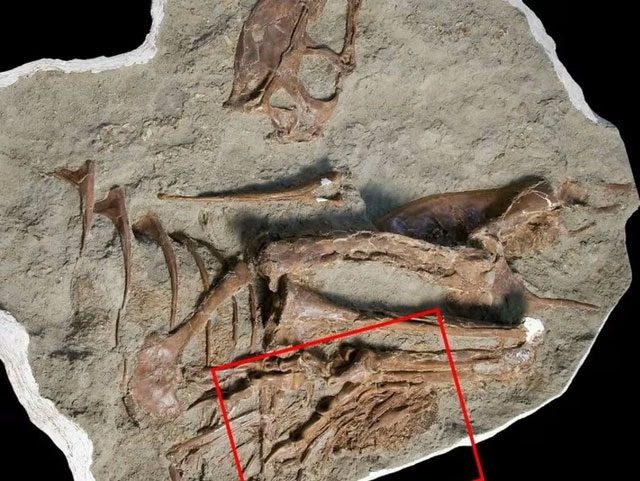

Prey intact in the stomach of the dinosaur fossil. (Photo: Reuters).

The Gorgosaurus had access to a vast array of prey and, therefore, could be selective about its meals. From 75 million years ago, in what is now Alberta, Canada, it chose a feathered herbivorous dinosaur named Citipes, roughly the size of a turkey, as its prey.

The fossil evidence shows that the Gorgosaurus consumed only the legs of the Citipes, ignoring the remaining flesh. The likely reason is that the prey was too large to swallow whole, prompting this Gorgosaurus to select the meatiest parts to eat.

Based on bite marks left on the prey’s bones, it can be concluded that adult Gorgosaurus could hunt even larger dinosaurs than Citipes.

The fossil was unearthed at the Dinosaur Provincial Park in southern Alberta, Canada. This area during the Cretaceous period was a coastal plain forest, located near the western shore of a vast inland sea that divided North America into two halves.

This is the first theropod fossil found with intact prey in its stomach.

Size difference between a Gorgosaurus and a Citipes. (Photo: Reuters).

This newly excavated fossil has provided deeper insights into the ecosystem of this dinosaur genus. It illustrates how the feeding habits and diet of theropod dinosaurs significantly varied throughout their lifetimes.

A study published in the journal Science Advances, led by François Therrien, a paleontologist at the Royal Tyrrell Museum (Canada), indicates that different species within the theropod family occupied various ecological niches at different times in their lifetimes. This means that juvenile theropods did not need to compete for prey with adults.