Black holes have long been regarded as one of the most complex and mysterious entities in modern science.

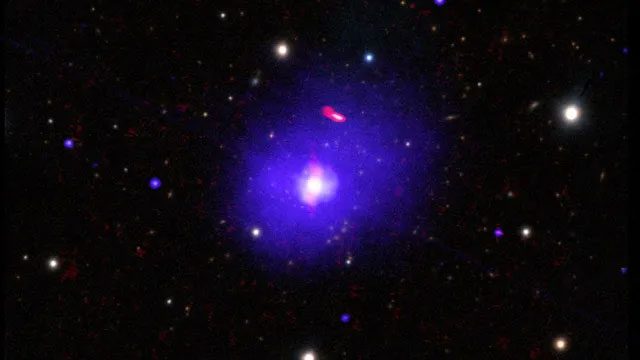

Typically, black holes spin very quickly—almost at the speed of light. However, astronomers have observed that a “monster” black hole spins much slower than most smaller black holes.

This new discovery may provide clues about how these supermassive black holes form. Located at the center of quasar H1821 + 643, approximately 3.4 billion light-years away from Earth, this supermassive black hole has a mass ranging from 3 billion to 30 billion times that of the Sun, making it one of the largest black holes ever discovered by scientists. For comparison, Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, is only about 4 million times the mass of the Sun. By analyzing data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, scientists have calculated the spin rate of this monster black hole.

Christopher Reynolds, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge and co-author of a study describing the findings, stated: “We found that the black hole in H1821 + 643 spins at only half the rate of most black holes that weigh around one million to ten million times the Sun.”

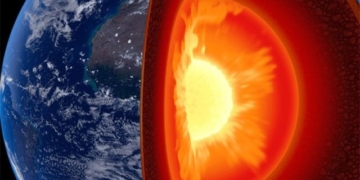

In simple terms, a black hole is a strange phenomenon created by the compression of matter to its limit. Theoretically, any form of matter can be compressed to its limit, from atoms to planets, provided that the pressure is sufficiently high, allowing it to become a black hole.

The research team believes the answer may help explain how supermassive black holes form. One leading hypothesis suggests that supermassive black holes form from collisions between two smaller black holes. During the intense merger process, the black holes can undergo significant changes in spin as gravity pulls them in different directions. This may cause the supermassive black hole to spin more slowly. In contrast, smaller black holes (non-supermassive) are thought to form by accumulating matter from an accretion disk around them, with matter entering their spin in a single direction, allowing these black holes to quickly accelerate.

If this hypothesis is correct, younger supermassive black holes typically have slower spin rates, while older supermassive black holes have had time to establish a stable spin direction and will be spinning faster. Overall, a range of spin rates will be found among supermassive black holes.

Determining the spin rate of the supermassive black hole H1821 + 643 brings us one step closer to the answer, but scientists will need to study the spin rates of even larger supermassive black holes to validate this idea.

In the universe, the smallest recorded black hole has a mass three times that of our Sun. These black holes form due to uncontrolled nuclear fusion within massive stars as they die, leading to a supernova explosion. The extreme pressure compresses the core material to the Schwarzschild radius equal to its mass, thus becoming a black hole. It is commonly believed that a star with a mass 30 to 40 times that of the Sun will directly transform into a black hole upon its death. Moreover, cosmic black holes can also form due to the collision and accumulation of massive celestial bodies, which collapse and form black holes when they exceed the mass limit. For example, through the accumulation process, a neutron star that exceeds the Oppenheimer limit will be compressed into a black hole. Theoretically, the mass of a black hole lies at the singularity of its core, and this singularity is infinitely small, making the black hole understood as having infinitely small volume, infinite density, infinite curvature, and infinite heat. The curvature of a black hole is infinite, referring to the Schwarzschild radius, and its critical point is also known as the event horizon of the black hole. Here, the curvature represents the distortion of the surrounding spacetime caused by mass, manifested as gravitational force. At great distances, its gravitational force still follows the law of universal gravitation, proportional to mass and inversely proportional to the square of the distance, just like the gravitational force of any celestial body. Because the gravitational force within the Schwarzschild radius of a black hole is infinite, any matter near the black hole will be “devoured” with no way to return, causing the black hole to grow larger. The largest black hole found in the universe is named SDSS J073739.96 + 384413.2, with a mass 104 billion times that of the Sun. |