When we learn that the inventor of cotton candy was William Morrison, an American dentist living in the late 19th century, many of us might question his ethics. Aren’t those sweet sugar confections likely to cause cavities in children, which is exactly why their parents pay dentists?

However, the reality seems to be different.

William Morrison, an American dentist who invented cotton candy.

To understand why Morrison invented the cotton candy machine, we need to go back to the 1900s to explore the context.

This was a time when states across America hosted summer fairs continuously. Here, you could find various games for children, from Ferris wheels and giant slides to circuses, outdoor performances, and, of course, snacks and candies.

From corn dogs, popcorn, funnel cakes, caramel apples to soft pretzels and snow cones… these traditional foods are still served at street fairs in America today.

What they all have in common is that they are very sweet, loaded with sugar, and extremely appealing to children. As a dentist, Morrison certainly knew this. It seems he wondered: How can I create a sweet treat that looks large and attractive but contains less sugar and fewer calories than those traditional snacks?

Traditional fair foods in America.

A cotton candy clearly met that goal. It is essentially just a teaspoon of sugar but fluffed up with over 90% of its volume being air. Therefore, a cotton candy can appear very large while containing only 105 kcal compared to 230 kcal of a bag of popcorn, 290 kcal of a caramel apple, 350 kcal of a corn dog, and 730 kcal of a funnel cake.

The sugar content in a cotton candy is also 12 times less than that of a regular soda can.

Moreover, the strands of cotton candy create a large surface area that interacts with taste receptors on the tongue. They appear larger and stimulate the taste buds better. With a small amount of sugar, cotton candy can satisfy children much more than other types of candy.

Thus, this is clearly a good invention for children. They would have a healthier food option compared to other sugary snacks. Of course, this means they would have to visit the dentist less often.

A young girl eating cotton candy.

When cotton candy was first introduced at a fair called the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, Morrison sold nearly 70,000 cotton candies and earned $17,000. Adjusted for today’s currency, that’s over half a million USD, exactly $560,000, a sum significant enough for him to consider closing his dental practice.

But how exactly did Morrison invent cotton candy?

In fact, before cotton candy was invented, European chefs had discovered the important property of sugar since the 15th century, allowing them to transform it from a solid to a liquid and then back into a solid strand. In Vietnam, we know a version of this candy as “kẹo kéo.”

Specifically, the strands of “kẹo kéo” are made from granulated sugar, the crystals known as sucrose. These are essentially molecules of glucose and fructose linked together by a chemical bond.

When you apply heat to sugar, this chemical bond breaks, releasing the small sugar molecules from their crystalline network. If you continue to heat these sugar molecules, they will break down further, releasing individual atoms that make up sugar, including carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

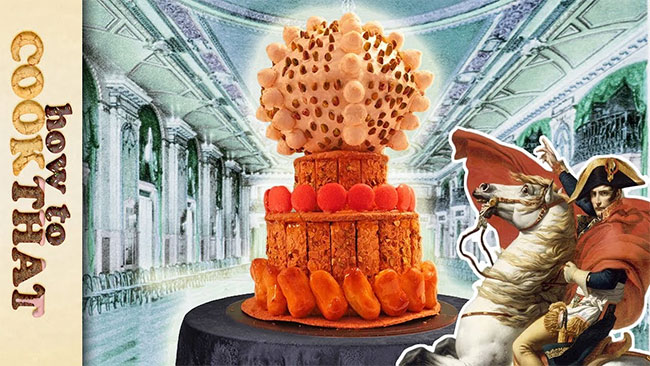

Chefs in Venice in the 15th century used their forks to dip into the melted sugar mixture and quickly pulled to create strands of sugar for decorating desserts.

The hydrogen and oxygen atoms recombine to form water, causing the sugar to melt into a liquid. Meanwhile, carbon can clump together into larger pieces. If you continue to heat until the water evaporates, the carbon begins to burn, and you will see charcoal appear.

However, if you only heat the sugar until it liquefies and then reduce the heat, you can pull it into strands. Chefs in Venice in the 15th century used their forks to dip into the melted sugar mixture and quickly pulled to create strands of sugar for decorating desserts.

Even the wedding cake of Napoleon Bonaparte was decorated with such sugar strands. Hundreds of years ago, such an artistic dessert was only seen at parties for the wealthy.

Until the 20th century, decorative sugar strands were only found at noble parties.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that William Morrison popularized the pulled sugar method and elevated it to new heights with his cotton candy machines. This opportunity came from his collaboration with a candy manufacturer named John Wharton.

Since 1899, they had improved several types of candy machines and started working on a machine to pull sugar into strands, replacing the manual work of chefs. Instead of melting sugar in a pan, Morrison and Wharton thought they could do it using a heated wire funnel powered by electricity.

If using a fork to pull sugar strands was too labor-intensive and manual, Morrison and Wharton designed a motor to spin the sugar funnel, utilizing centrifugal force to fling the sugar strands through small holes.

How to make cotton candy.

When the speed of the funnel increased to over 3,000 revolutions per minute, Morrison and Wharton found they could create ultra-thin sugar strands, as thin as 50 micrometers, equivalent to the fine hair on your head.

The sugar strands meet cold air and quickly cool down, crystallizing back into an amorphous solid. Morrison and Wharton could use a stick to collect all the sugar strands as they spun around the machine’s chamber.

Initially, they called these crystals “fairy floss” because they appeared white, massive, and very eye-catching. This name is still used for cotton candy in Australia. In other countries, cotton candy is also known by catchy names such as “dragon beard” in China, “sugar thread” in the Netherlands, and “Old Ladies’ Hair” in Greece.

A food engineering professor explains the principle of making cotton candy

But cotton candy is not just an invention that satisfies children and adults looking to relive their childhood. The principle of creating amorphous crystals with the cotton candy machine has also been applied by scientists to create capillary systems.

In a study, doctors at Cornell University and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital observed that the size and arrangement of cotton candy strands closely resemble the capillary systems in the human body.

Using a mechanism similar to that of the cotton candy machine, scientists can create protein scaffolds and blood vessels to grow artificial meat. They can also use it to create organ tissues suitable for transplantation.

And that is the history, as well as the present and future, of cotton candy.