To date, scientists have been unable to explain the phenomenon that causes discrepancies between expected and recorded motion when a spacecraft flies past a planet.

On December 8, 1990, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft experienced an “anomalous flyby of a celestial body” while passing Earth on its way to Jupiter and its moons. This anomaly has been noted in several other spacecraft since then and remains a mystery that has yet to be clarified, according to IFL Science.

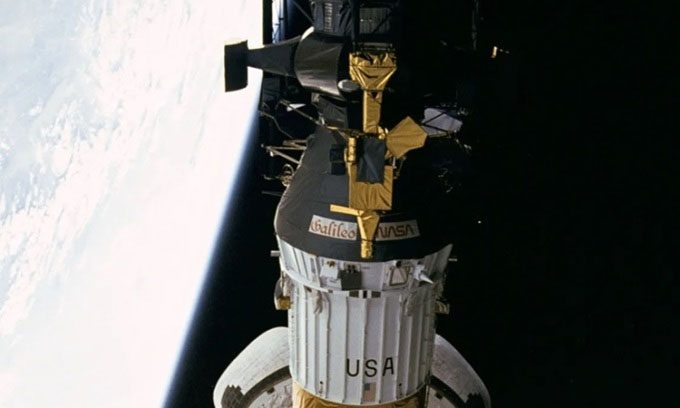

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. (Photo: NASA).

In missions exploring celestial bodies in the Solar System, NASA often employs “gravitational assists.” This technique allows spacecraft to use relative motion and leverage the gravity of other planets or celestial bodies to change direction and increase speed, while also reducing costs and saving propulsion fuel. Essentially, the spacecraft will “borrow” a bit of momentum from the planet or star. Several automatic spacecraft use gravitational assist techniques to reach their targets.

Voyager 2 was launched in August 1977 and passed Jupiter for exploration and acceleration on its way to Saturn, according to NASA. Voyager 1, launched in September of the same year, did the same and reached Jupiter before Voyager 2. Voyager 2 then used gravitational assists from Saturn and Uranus to fly to Neptune and beyond. The Galileo spacecraft relied on gravitational assistance from Venus and Earth as it orbited the Sun on its way to Jupiter. Cassini borrowed gravitational assists twice from Venus, once from Earth, and once from Jupiter to accumulate enough momentum to reach Saturn.

NASA has frequently utilized gravitational assists around Earth. Analyzing six flybys of the Galileo, NEAR, Cassini, Rosetta, and MESSENGER spacecraft, researchers discovered several instances where the spacecraft’s acceleration exceeded expected levels from this maneuver. They noted that there was an unusual energy change during those flybys of Earth, although they could not identify a clear cause or system error behind it. The research team suggested that the effect might be related to Earth’s rotation. However, they did not rule out other explanations, ranging from relativistic effects to dark matter halos around Earth.

The situation becomes even more complex as some spacecraft, including Juno, did not experience anomalies while using gravitational assists, indicating that there are exceptions and more data from future flybys are needed to draw conclusions.

In 2013, Stephen Adler, a particle physicist and emeritus professor at the Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, proposed a model in which Earth is wrapped in two layers of dark matter. According to his hypothesis, the spacecraft’s acceleration and deceleration are due to the elastic and inelastic properties of these two layers. He predicted that NASA’s Juno would fly by Earth in October 2013 with a velocity deviation of 11.6 millimeters/second compared to the expected speed. However, Juno’s journey to Jupiter proceeded without discrepancies from the original calculations. Adler argued that this example helped eliminate the hypothesis that dark matter influenced the spacecraft’s speed. Instead, he suspects that the speed discrepancies of some earlier spacecraft resulted from measurement device errors.