In Vietnam, an international team of scientists unexpectedly discovered a type of meat for a sustainable future for both the planet and humanity. What type of meat is it?

Amid the escalating climate crisis, scientists are urgently seeking sustainable solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on a global scale. They have been promoting green solutions such as reducing fossil fuel consumption, increasing renewable energy production, and developing new production processes to make everything more environmentally friendly.

These shifts are occurring on all fronts, from plastic straws to grass straws, from thermal power to solar energy, and from gasoline vehicles to electric vehicles. However, there is one sector that significantly contributes to climate issues but has yet to experience a clear transition: livestock farming.

There is an undeniable fact that the livestock industry is one of the primary causes of global warming.

In their quest for a more eco-friendly and sustainable meat option, a team of international scientists from Macquarie University and the University of Adelaide (Australia), the University of Oxford (UK), and the University of Witwatersrand (South Africa) traveled to Vietnam.

Here, they believe they have found the answer to a type of meat that could help humanity reduce greenhouse gas emissions and decrease the land area required for agriculture, thus allowing for the expansion of green forests that help slow the climate change process.

A “Green” Protein Source

The type of meat that the international research team discovered is snake and python meat. In a study published in the journal Science Reports, the scientists reported that they spent over a year in Vietnam researching the growth process of thousands of Malayopython reticulatus snakes and pythons.

These snakes were raised on commercial farms in Ho Chi Minh City and An Giang to produce skins for the leather and high-fashion industries. However, snakes and pythons can also be sold for their meat, which is of very high quality.

Malayopython reticulatus.

Prominent among the reptiles in Vietnam is the reticulated python. They can grow up to 6 meters long, containing approximately 150 kg of white meat, which is healthier than red meat from livestock. This amount of meat is efficiently converted from limited food sources.

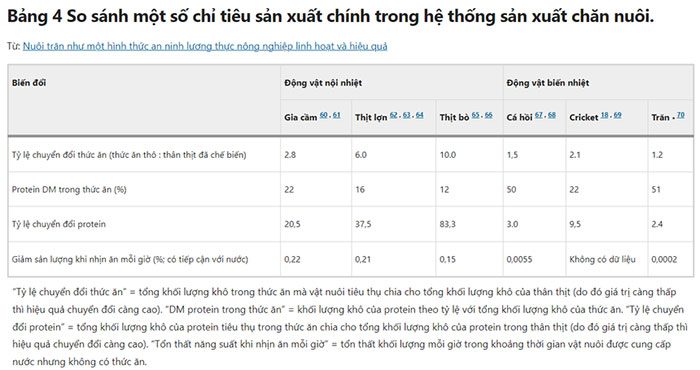

The scientists noted that pythons raised in Vietnam typically eat mice, by-products from pork, chicken, and fish, but they grow very quickly from the first year. Compared to pigs, cattle, chickens, and even salmon, pythons require less food to produce each kilogram of meat, a scientific term known as feed conversion ratio.

Every day, a python in Vietnam can gain up to half a kilogram of meat. This is due to the low feed conversion ratio of the python species. They only need to consume 1.2 kg of dry protein to produce 1 kg of meat. In contrast, the figure is 1.5 times higher for salmon, 2.1 times for crickets, 2.8 times for poultry, 6 times for pigs, and 10 times for cattle.

The lower the feed conversion ratio, the better. With the same amount of feed, you can produce 8 kg of python meat compared to 1 kg of beef.

A python eating “recycled sausages” made from pork, chicken, and fish by-products.

Study image.

“The feed conversion ratio and protein of pythons surpass all species present in conventional human agriculture to date,” emphasized Dr. Daniel Natusch, the lead author of the study from Macquarie University. “Pythons grow very quickly, reaching ‘slaughter weight’ within their first year after hatching from eggs.”

From an environmental perspective, pythons also have advantages. At the same weight ratio, reptiles like snakes and pythons produce less greenhouse gas than mammals. This is because they have a healthier digestive system capable of digesting bones in their food and produce minimal waste. Reptiles excrete less feces than mammals such as pigs, buffalo, and cattle.

Water consumption is even more impressive. “Pythons need very little water and can even survive on dew that collects on their scales in the early morning. Each morning, a python only needs to lick its scales, and that’s enough water for the entire day,” Dr. Natusch stated.

This is very beneficial for python farming in areas frequently affected by drought due to climate change. Pythons can survive for up to a month without drinking a drop of water.

Each morning, a python only needs to lick its scales, and that’s enough water for the entire day.

Additionally, pythons can fast for extended periods without significant weight loss. A python in Vietnam can go without food for 127 days but only loses a few percent of its body weight. Dr. Natusch noted: “Theoretically, you could stop feeding it for a year.”

Python farmers can completely cease feeding them if conditions do not permit. Dr. Natusch cited an example during the COVID-19 pandemic when farmers could not sell pigs due to supply chain disruptions. Since continuing to feed pigs was too costly, they had to cull the pigs and turn the pork into fertilizer.

“At that time, I just wished those farmers had raised pythons,” he said.

Can the Python Farming Model in Vietnam Be Expanded Globally?

Despite the advantages of pythons, their meat is only popular in a few Asian countries such as Thailand, China, and Vietnam. In Thailand, people commonly raise the Burmese python (Python bivittatus). Meanwhile, in China, pythons are also raised for medicinal purposes, food, and to supply skins for high fashion.

It is estimated that there are over 4,000 farms raising snakes and pythons in Vietnam and China, producing millions of animals each year. Can this scale of farming be expanded globally?

Estimated over 4,000 snake and python farms in Vietnam and China, producing millions of animals each year.

Dr. Natusch noted that there are advantages supporting that future, but also barriers that need to be overcome.

Regarding advantages, python farming requires very low investment capital, meaning the barrier to entry is much lower than in other traditional livestock industries. There is no need for complex breeding, no need for large housing systems, and python farmers in Vietnam can currently utilize their backyards or warehouses to convert them into small python farms.

Each python requires a cage of about 2 square meters for basic living needs. They are inherently less active and can happily coexist with other pythons. “Pythons also exhibit fewer complex animal welfare issues typically seen in caged birds and mammals,” the researchers stated.

While some conservationists express concern that commercial snake and python farming could lead to illegal hunting of wild populations, Dr. Natusch argues that the opposite has occurred. The python farming industry creates financial incentives for local communities to develop and conserve wild snake populations and their habitats.

In his research in Vietnam, Dr. Natusch found that some farms even hire local residents, often retirees, to raise juvenile pythons for a year. They would take the pythons home, catch mice for them to eat, and then sell them back to the larger farm. Locals do not need to hunt wild pythons or snakes for additional income.

Pythons being fed mice at a farm in An Giang.

With these advantages, scientists believe that python farming in Vietnam can be introduced to other countries, especially in African nations, which are facing food insecurity due to increasing climate disasters and outdated farming techniques.

Imagine farmers in Africa catching mice in their cornfields while feeding pythons to obtain a higher quality and more sustainable protein source for their livelihoods.

However, expanding the model of snake farming faces several barriers. The first challenge is cultural. In many East Asian countries, snakes and pythons have long been regarded as valuable medicinal products, so using them as food is even encouraged.

Speaking about dishes made from python and snake meat, Dr. Natusch mentioned that he has tried a variety of dishes including python soup, stir-fried snake, grilled snake, python curry, and snake floss. “Basically, their meat tastes like chicken, but with a hint of wild game flavor,” he stated.

A python slaughtering line right at the farm.

Since snakes have no legs, their meat can be processed very efficiently. There is very little waste during the slaughtering process. In particular, they are very easy to fillet. “You just need to run a knife along their spine and you’ll have a piece of meat up to 4 meters long,” Dr. Natusch said.

“Reptile meat is similar to chicken: high in protein, low in saturated fat, and has broad aesthetic and culinary appeal,” the scientists wrote in the paper. However, it has yet to gain acceptance in Western markets.

Back in his homeland, Dr. Natusch noted that Australians often say: “The only good snake is a dead snake. People in our country are quite afraid of them.”

Although pythons are non-venomous and generally move slower than snakes, they have large teeth and can bite if provoked. There have been many incidents where wild pythons invaded human habitats and preyed on pets, such as cats and dogs.

“I think it will be a long time before you see python burgers served at your favorite local restaurant in Australia,” Dr. Natusch commented.

A plate of grilled snake sausage.

A bowl of python soup.

However, with his new research, Dr. Natusch aims to change Western perceptions of python meat.

“Our research confirms previous studies that breeding and farming pythons in captivity for commercial purposes is biologically and economically feasible,” he wrote in an article published in Science Reports.

In a world facing numerous issues caused by climate change, python meat in particular, and reptiles like snakes in general, could become part of the simple solution.

Pythons and snakes provide a greener source of protein for humanity, help eliminate pest species that damage crops, address hunger in many countries, and reduce emissions from poultry and livestock farming.

Perhaps it is time we should incorporate dishes made from snake and python meat into the human diet.