In November 1977, health agencies in Russia reported the discovery of a human virus strain that was not the H1N1 influenza strain in Moscow, the capital of Russia…

Private David Lewis, a 19-year-old member of the U.S. Army, departed from Fort Dix on February 5, 1976, for a nearly 80 km march with his unit. On that frigid day, he collapsed and died. His autopsy sample unexpectedly tested positive for the H1N1 swine flu virus.

Swine flu vaccination campaign in 1970. Photo (CDC/Wikimedia Commons).

The surveillance team for the virus outbreak at Fort Dix identified 13 additional cases among recruits hospitalized for respiratory illness. Supplemental antibody testing showed that over 200 recruits had been infected with the same virus but did not require hospitalization.

Immediately, alarms rang out in the epidemiology community: Was Private Lewis’s death from H1N1 swine flu a harbinger of another global pandemic similar to the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic, which killed about 50 million people worldwide?

The U.S. government acted swiftly. On March 24, 1976, President Gerald Ford announced a plan to “vaccinate every man, woman, and child in America.” On October 1, 1976, the mass vaccination campaign began.

Meanwhile, the initial small outbreak at Fort Dix quickly subsided, with no further cases reported after February 1976. Colonel Frank Top, who led the virus investigation at Fort Dix, later stated, “we have clearly demonstrated that the virus did not go anywhere else but Fort Dix. It has disappeared.”

Despite this, concerns about the outbreak and witnessing the large-scale vaccination program in the U.S., biomedical scientists around the world began research and development programs for the H1N1 swine flu vaccine in their respective countries. As winter 1976-1977 approached, the world braced for a swine flu pandemic that never occurred.

However, the story did not stop there.

Professor Donald S. Burke from the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Public Health noted that as an infectious disease epidemiologist, he believed there were unforeseen consequences from the seemingly cautious but ultimately unnecessary preparations by the world.

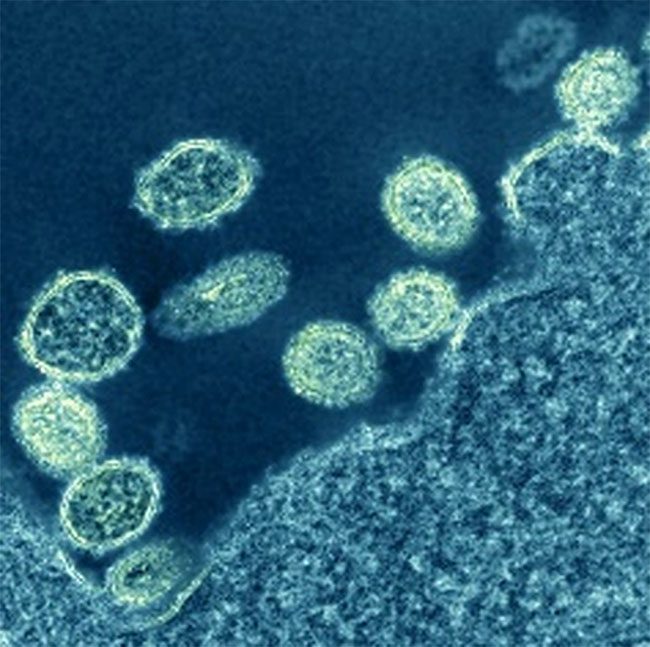

H1N1 virus particles near a cell, under microscope in 1918 (Photo: NIAID).

The Peculiar Pandemic of H1N1 in Russia

In an epidemiological twist, a new pandemic influenza virus emerged, but it was not the H1N1 swine flu as anticipated.

In November 1977, health agencies in Russia reported that a human virus strain, distinct from H1N1, had been identified in Moscow. By the end of November, reports indicated it had spread throughout the Soviet Union and soon thereafter worldwide.

Compared to other influenza illnesses, this pandemic was remarkably different.

- First, the mortality rate was low, only one-third that of most other influenza strains.

- Second, it predominantly affected individuals under the age of 26.

- Finally, unlike the emerging pandemic influenza viruses at the time, it did not replace the H3N2 subtype as the seasonal flu virus that year; instead, both strains: the new H1N1 and the long-standing H3N2 coexisted.

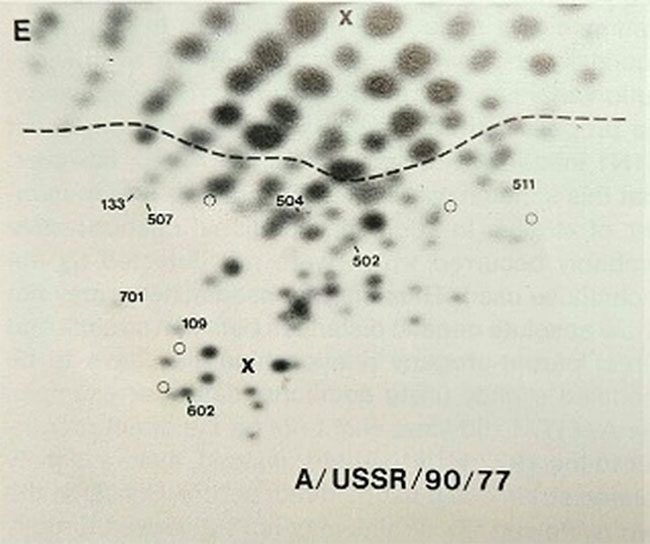

At this point, the narrative took another turn. Microbiologist Peter Palese employed a then-new technique called oligonucleotide RNA mapping to study the genetic structure of the 1977 Russian H1N1 influenza virus.

He and his colleagues cultured the virus in the laboratory, then used RNA-cutting enzymes to slice the viral genome into hundreds of pieces, mapping out similarities like unique fingerprints.

To his surprise, when the research team compared the 1977 Russian H1N1 virus to numerous other influenza viruses, this new virus was essentially identical to the H1N1 strains that had gone extinct in the early 1950s.

Researchers were astonished to find the “genetic fingerprint” of the 1977 Russian H1N1 strain nearly identical to that of the extinct virus. (Photo: Peter Palese).

Thus, the 1977 Russian flu virus was actually a strain that had vanished from the planet a quarter-century earlier, which somehow re-emerged. This explains why it primarily affected younger individuals: the older population had been infected and became immune when it reappeared.

But how did this old strain come back after being extinct?

Revising the Timeline of the Resurrected Virus

Despite its name, it is very likely that the Russian flu did not actually originate in Russia. The first reports of it were in Russia, but subsequent reports from China provided evidence that it was first detected months earlier, in May or June 1977, in the port city of Tianjin, China.

In 2010, scientists used detailed genetic studies of several 1977 virus samples to determine the timing of the common ancestor of these viruses. The “molecular clock” data indicated that the original virus infected humans as early as April or May 1976.

Thus, the most compelling evidence indicates that the 1977 Russian flu actually resurrected, or more accurately, “re-emerged,” in or near Tianjin, China, in the spring of 1976.

A Frozen Virus in the Laboratory

Could it be mere coincidence that just months after Private Lewis’s death due to H1N1 swine flu, an extinct H1N1 strain suddenly re-entered the human population?

Influenza virologists around the globe had been using freezers for years to store influenza strains, including some that had gone extinct in nature. The concerns over the H1N1 swine flu pandemic in 1976 in the U.S. spurred increased research into H1N1 viruses and vaccines worldwide.

An accidental release of one of these stored viruses likely occurred in a country conducting H1N1 research, including China, Russia, the U.S., the U.K., and possibly other nations.

Professor Palese suggested that the emergence of the 1977 H1N1 virus was likely a result of vaccine trials in the Far East involving challenges with thousands of recruits infected with live H1N1 virus.

While the exact nature of how the virus was accidentally released during vaccine trials remains unclear, two major possibilities exist.

First, scientists might have used the re-emerging H1N1 virus as a starting material to develop a live attenuated H1N1 vaccine. If this virus in the vaccine was not sufficiently weakened, it could have become transmissible from person to person.

The second possibility is that researchers used live virus, revived it to test immunity after conventional H1N1 vaccination, and this virus inadvertently escaped from the research facility.

Regardless of the mechanism leading to that loss, the combination of the specific location and timing of the pandemic’s origin, along with Professor Palese’s credibility, provides a reliable basis for concluding that the accidental release of this virus from China was the source of the pandemic-causing Russian flu virus.

A Thought-Provoking Historical Lesson

The resurgence of a dangerous extinct H1N1 virus occurred while the world was simultaneously trying to prevent another influenza pandemic, resulting in less catastrophic consequences.

According to Professor Palese, given the limited understanding of epidemiology at that time in 1976, alongside the growing global concern about an impending pandemic, any research unit could have accidentally released the resurrected virus known as the Russian flu.

Of course, biosafety protocols and facilities have significantly improved over the past half-century. High-security laboratories are also continuously evolving worldwide.