About 4,000 years ago, the last woolly mammoth on Earth died alone on an island in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Siberia, Russia.

This is a tragic end for one of the most captivating species from the Ice Age in the world. But what led to the extinction of this last population of mammoths on Wrangel Island? New genetic analyses shed light on this mystery.

So far, this study provides the most comprehensive information regarding the inbreeding, harmful mutations, and low genetic diversity faced by this population during its 6,000 years of isolation on the island, but concludes that, despite previous suggestions, these factors are unlikely to have caused the extinction of the Wrangel mammoths.

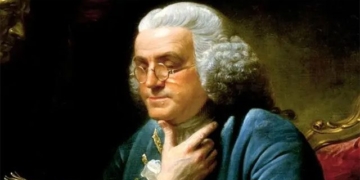

Illustration of the last woolly mammoth on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Siberia, Russia. (Source: Reuters).

Evolutionary geneticist Marianne Dehasque from Uppsala University in Sweden, the lead author of the study published on June 27 in the journal Cell, stated: “The facts suggest that something different and very abrupt caused the mammoth population to collapse.”

The researchers examined genetic data obtained from the remains of 14 Wrangel mammoths and 7 mammoths from a population on the Siberian mainland, the ancestors of the island’s inhabitants, dating back up to 50,000 years.

As the Ice Age waned, the dry tundra where mammoths thrived gradually transformed from south to north into wetter temperate forests amid rising global temperatures, trapping these animals in the far north of the Eurasian continent.

“This is likely also the reason why the last mammoth was isolated on Wrangel Island, which became disconnected from the mainland around 10,000 years ago due to rising sea levels. There may have only been a single herd residing on the island,” said Dehasque.

Evolutionary geneticist Marianne Dehasque with a mammoth tusk in Stockholm, Sweden. (Source: Reuters).

The genetic data indicate that the isolated population on Wrangel Island originated from a maximum of 8 individuals, which then increased to 200 to 300 mammoths over about 20 generations—roughly 600 years—and remained stable.

The study found a decline in diversity within an important gene group related to the immune system. However, while mammoths gradually accumulated harmful mutations at a moderate rate, the most detrimental defects appeared to have disappeared from the population, likely because individuals carrying these mutations had lower survival and reproductive success.

The study did not include genetic data from the last 300 years of the population, but the remaining samples have now been excavated and are planned for genetic analysis.

Previous studies suggested that extinction was due to accumulated genetic defects.

“We do not believe that inbreeding, low genetic diversity, or harmful mutations were the reasons for the population’s extinction because if that were the case, the population would have likely experienced a gradual decline in size, leading to extinction at a faster rate, accompanied by increased inbreeding and loss of diversity,” said evolutionary geneticist Love Dalén from the Center for Palaeogenetics, a collaboration between Stockholm University and the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

“But this is not what we observe. There was virtually no change in inbreeding levels or genetic diversity throughout the 6,000 years that mammoths were isolated on the island. This means that the population size remained stable over time,” Dalén added.

Scenery on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Siberia, Russia. (Source: Reuters).

Human hunting does not appear to be the culprit. “I agree that the mystery of the mammoth’s death remains. But from archaeological evidence, we know that humans only arrived here 400 years after the mammoths went extinct,” Dehasque said.

According to Dalén, it is easy to find hearths and shelters, as well as flint fragments, bones, and reworked tusks, etc. However, there is no evidence that humans interacted with mammoths on Wrangel Island.

Scientists suggest that a disease brought by birds to the island could be a possibility. “Perhaps mammoths were vulnerable to this due to the reduced diversity we identified in their immune system genes. Additionally, something like tundra wildfires, volcanic ash, or really bad weather could have resulted in a year of very poor growth for the species. The vegetation on Wrangel Island is sparse, making it susceptible to such random events,” Dalén further explained.