Cancer cells can die quietly and be recycled, but sometimes they also stimulate nearby surviving cancer cells to grow.

Cancer treatments such as chemotherapy kill tumor cells, often by causing them to self-destruct, shrink, and die quietly, or sometimes by triggering a more intense form of cell death. But what happens to cancer cells after they die?

Typically, they are recycled just like any other dead cells in the body. When cancer cells die, their outer membranes are often damaged. This occurs in the form of “quiet” cell death known as apoptosis, a predetermined process designed to eliminate unnecessary or damaged cells.

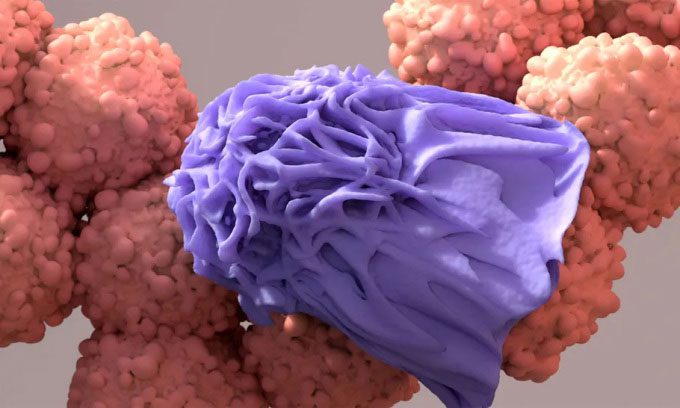

Phagocytes, a type of immune cell, engulf and recycle dead cancer cells. (Image: Design Cells).

When the molecular switch that activates apoptosis is “turned on”, the dying cell shrinks and membrane fragments leak out through bulges. This causes the cell’s internal components to leak out and attract phagocytes—immune cells responsible for engulfing cellular debris.

Phagocytes will envelop the dead cancer cells and then break them down into smaller components like sugars and nucleic acids. Through this process, dead cancer cells are recycled into substances that other cells can reuse later. In apoptosis—the type of cell death targeted by traditional cancer therapies—fragments of dead cancer cells are often recycled in this way rather than being expelled from the body, for example, through urine.

Cancer treatment therapies can also induce other types of cell death such as necroptosis—a type of “explosive” cell death in which tumor cells swell and burst instead of shrinking. Phagocytes also effectively eliminate these dying cells.

However, cancer cells do not always leave quietly. Research shows that when they release inflammatory debris, they can sometimes stimulate nearby surviving cancer cells to grow. This phenomenon is known as the Révész effect, helping to explain why some cancers recur after treatment.

A 2023 study by a team of experts at the National Cancer Institute found that the control center, or nucleus, of dying cancer cells can sometimes swell and burst, releasing DNA and other molecules into the surroundings. In mice, these molecules can accelerate metastasis—the spread of cancer cells beyond the original tumor.

Such studies help explain how dying tumor cells contribute to the progression and recurrence of cancer. However, research is still in a relatively early stage, and scientists do not yet fully understand this relationship.

With more research in the future, they aim to gain a better understanding of the biological mechanisms behind cancer, thereby developing more effective treatments. For instance, a 2018 study suggested a method to combat tumor growth caused by fragments of dead cancer cells based on resolvin—a molecule derived from omega-3 that may help reduce inflammation and the effects of cytokines, while promoting the clearance of cellular debris.