Tsunamis are among the most devastating natural disasters known to humanity.

What is a Tsunami?

A tsunami is a series of waves created when a large volume of ocean water is rapidly displaced on a massive scale. Earthquakes and significant geological shifts above or below the water’s surface, volcanic eruptions, and meteorite impacts can all trigger tsunamis. The catastrophic consequences of a tsunami can be immense, drowning hundreds of thousands of people within hours.

Tsunami.

The term tsunami originates from Japanese, meaning “harbor” (津 tsu, in Sino-Vietnamese: “tân”) and “wave” (波 nami, “ba”). This term was coined by fishermen who were unaware that the waves originated from far offshore. The tsunami starts from the deep ocean floor, where the wave amplitude (height) is relatively small, but the wavelength can extend to hundreds of kilometers. Therefore, when far from the shore, it is difficult to identify the tsunami; it merely feels like a long, rolling wave.

Causes of Tsunami Formation

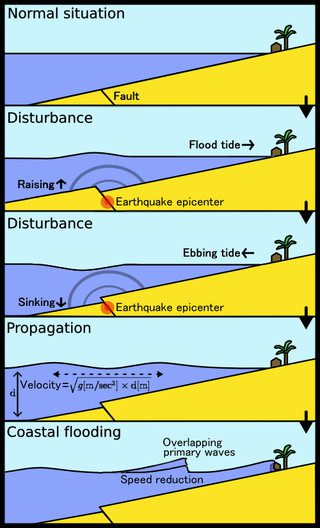

Tsunamis can form when the ocean floor is suddenly deformed vertically, displacing the water above it. Such large vertical movements of the Earth’s crust can occur at the edges of tectonic plates. Earthquakes caused by plate collisions can create tsunamis. When an oceanic plate collides with a continental plate, it sometimes causes the edge of the continental plate to move downward. Eventually, the excessive pressure on the edge of the plate causes it to snap back, creating shockwaves that propagate through the Earth’s crust, resulting in an underwater earthquake.

Undersea landslides (sometimes triggered by earthquakes) as well as volcanic collapses can also generate water columns that cause sediment and rocks to slide down the slopes into the ocean floor. Similarly, a strong underwater volcanic eruption can displace a significant volume of water, forming a tsunami. The waves are generated as the displaced water mass moves to regain equilibrium and spreads across the ocean like ripples on a pond.

Tsunami formation.

In the 1950s, it was discovered that large tsunamis could arise from landslides, volcanic eruptions, and meteorite impacts. These phenomena cause vast quantities of water to be displaced rapidly, with energy from a meteorite or explosion transferring into the water at the impact site. Tsunamis caused by these events are typically short-lived and rarely reach distant shores due to the localized nature of the events. However, a massive landslide can generate a tsunami that affects the entire ocean.

Characteristics of Tsunamis

Tsunamis behave very differently depending on the type of wave: they carry immense energy, propagate at high speeds, and can cover vast distances across the ocean while losing very little energy. A tsunami can cause damage on coastlines thousands of kilometers away from where it originated, allowing for several hours of preparation from the time it forms to when it crashes onto a shore. It appears a considerable time after the seismic waves generated by the event have traveled outward. The energy per meter of wave is inversely proportional to the distance from the source.

A single tsunami can consist of a series of waves with varying heights. In deep water, tsunamis have very long periods (the time for the next wave to reach a point after the previous wave), ranging from several minutes to hours, with wavelengths extending up to hundreds of kilometers. This is quite different from waves formed by normal wind on the ocean’s surface, which typically have a period of about 10 seconds and a wavelength of 150 meters.

Tsunami in Japan in 2011.

The actual height of a tsunami wave in the ocean often does not exceed one meter. This makes it difficult for those at sea to recognize them. Because they have large wavelengths, the energy of a tsunami affects the entire water column, directing it downward toward the ocean floor.

Tsunamis in deep water are typically caused by the movement of water from the surface to a depth equal to half the wavelength. This means that surface ocean waves only reach a depth of about 100 meters or less. In contrast, tsunamis behave like shallow water waves in the deep ocean (due to their wavelengths being at least 20 times greater than the depth at which they are occurring), as the dispersion of water movement is less pronounced in deep water.

A tsunami travels across the ocean at an average speed of 500 miles per hour. As it approaches land, the sea floor becomes shallower, causing the wave to slow down and begin to “stand up”; the front of the wave starts to steepen and rise, and the distance between successive waves decreases. While a person out at sea may not notice signs of a tsunami, once it reaches shore, it can reach heights of a six-story building or more. This standing up process is similar to cracking a whip. As the wave moves from the tail to the tip of the whip, the same amount of energy is distributed across an increasingly smaller mass, resulting in a more intense motion. As it moves inland, the speed decreases but the wave height increases.

A wave becomes a “shallow water wave” when the ratio between the water depth and its wavelength is very small, and because tsunamis have very long wavelengths (hundreds of kilometers), they behave as shallow water waves just outside the ocean. Shallow water waves travel at a speed equal to the square root of the product of gravitational acceleration (9.8 m/s²) and the water depth. For example, in the Pacific Ocean, at an average depth of 4,000 meters, a tsunami would travel at approximately 200 m/s (720 km/h or 450 mph) and lose very little energy, even over long distances. At a depth of 40 meters, the speed would be 20 m/s (about 72 km/h or 45 mph), slower than the speed at sea but clearly faster than any human can run.

Hawaiian residents fleeing from an incoming tsunami in Hilo, Hawaii.

Signs of an Impending Tsunami

The following signs often precede a tsunami:

- Feeling an earthquake. If the ground shakes violently enough that you cannot stand, a tsunami is likely to follow.

- Gas bubbles rising to the water’s surface, making it feel as if the water is boiling.

- Unusually warm water.

- Water that smells like rotten eggs (hydrogen sulfide) or gasoline, oil.

- Water causing skin irritation.

- Hearing a sound similar to a jet engine, helicopter blades, or whistling.

- The sea noticeably receding.

- Dark clouds swirling in the sky.

- A red streak on the horizon.

- When the tsunami hits the shore, there will be a rumbling sound like a train approaching.

- Millions of seagulls flying away from the sea.

- Many countries have tsunami warning sirens that sound when a tsunami is imminent.

Why Are Tsunamis So Dangerous?

Tsunamis are not always massive waves when they reach the shore. According to the USGS, “most tsunamis do not produce waves like the typical rolling surf at the beach as they approach the shore. Instead, they resemble a very strong and rapid tide – meaning the sea level rises quickly and locally.”

By now, you likely have a clear idea of why tsunamis are so dangerous. They can be extremely long (often 100 km), very high (the 2011 tsunami in Japan measured over 10 meters), and can move incredibly fast while losing little energy. A large earthquake in the ocean can cause several devastating tsunamis hundreds or even thousands of kilometers away.

In 2004, an earthquake with a magnitude of 9.1–9.3 struck off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The Indian Plate was subducted beneath the Myanmar Plate, triggering a series of catastrophic tsunamis, some exceeding 30 meters in height. The tsunami killed over 230,000 people in 14 countries and became one of the largest natural disasters in human history. This is just one of many tragic examples highlighting the immense power of tsunamis.

What is an Earthquake? How are Earthquakes Formed?

The Russian Scientists’ Plan to Clone the Extinct Bison 8,000 Years Ago

A “Cosmic Gun” 20 Times Larger than Earth Appears, and on March 31, the Earth Faces a Major “Storm”