When mountaineers ascend to the summit of Everest, they often need to carry oxygen tanks, equipment that allows them to breathe freely at high altitudes. This is necessary because, as you approach the edge of Earth’s atmosphere, the available oxygen decreases, especially in comparison to the abundant oxygen found near sea level.

This is just one example of how Earth’s atmosphere changes. It also illustrates the elemental composition within its layers, from the troposphere, which is closest to sea level, to the exosphere, at its outermost regions.

According to the National Weather Service, each layer’s beginning and end is determined by four main characteristics: temperature variation, chemical composition, density, and the movement of gases within it.

So, where does Earth’s atmosphere actually end? And where does space begin?

Earth’s atmosphere has layers with distinct characteristics.

Each layer of the atmosphere plays a crucial role in ensuring that our planet can sustain all forms of life. It does everything from blocking harmful cosmic radiation to creating the necessary pressure for water production, according to NASA.

“As you move further away from Earth, the atmosphere becomes less dense,” shared Katrina Bossert, a space physicist at Arizona State University. “The composition also changes, with lighter atoms and molecules beginning to dominate while heavier molecules remain closer to Earth’s surface.”

As you ascend in the atmosphere, the pressure or weight of the atmosphere above decreases rapidly. Although commercial airplanes have pressurized cabins, the quick change in altitude can affect our thin Eustachian tubes that connect our ears, nose, and throat. Matthew Igel, an assistant professor of atmospheric science at the University of California, Davis, stated: “This is why your ears may pop when a plane takes off.”

Ultimately, the air becomes too thin for conventional aircraft to fly because they cannot generate enough lift. This is the area where scientists have decided to mark the end of the atmosphere and the beginning of space.

This boundary is known as the Kármán line, named after Theodore von Kármán, a physicist with dual American-Hungarian-German citizenship. In 1957, he was the first to attempt to define the boundary between Earth and outer space.

The Kármán line, as it marks the boundary between Earth and space, not only indicates where the limits of conventional aircraft lie but is also crucial for scientists and engineers as they figure out how to keep spacecraft and satellites successfully orbiting Earth. Physicist Bossert noted: “The Kármán line is an approximate region that indicates the altitude at which satellites can orbit Earth without burning up or falling out of orbit before making at least one complete revolution around the planet.”

“It is typically defined as being 100 km from Earth,” Igel added. “Something could technically orbit Earth at an altitude below the Kármán line, but it would require an extremely high orbital speed, difficult to maintain due to friction. However, there is nothing that prohibits that.”

“It’s a conceptual threshold but represents the actual divide between aviation and space travel,” he further explained.

According to Bossert, various factors, such as the size and shape of the satellite, play a decisive role in determining the level of atmospheric drag and thus affect its ability to successfully orbit Earth. Typically, satellites in low Earth orbit—often classified as those at altitudes below 1,000 km, but sometimes as low as 160 km—will re-enter the atmosphere after a few years due to “drag from the upper layers of Earth gradually slowing their orbital speed.”

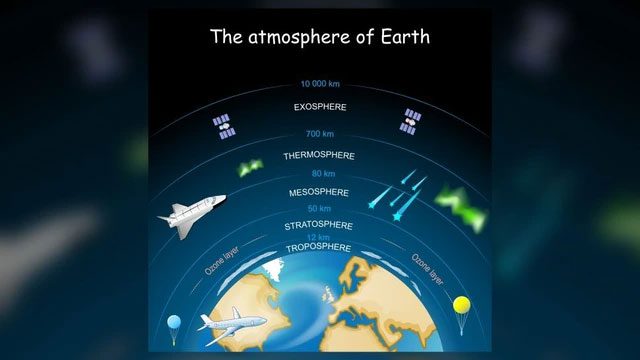

Illustration of the layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

However, this does not mean that Earth’s atmosphere cannot be detected beyond 1,000 km.

“The atmosphere does not disappear once you enter the region where satellites orbit,” Bossert stated. “It extends thousands of kilometers further before evidence of Earth’s atmosphere ceases to exist. The outer atoms of Earth’s atmosphere, such as hydrogen atoms that make up its exosphere, can even extend beyond the Moon.”

So, if someone were to reach the Kármán line, would they notice anything? Would they realize that they are essentially at the boundary between Earth and space?

“Nothing really changes,” Bossert said.

“This line is not a physical boundary, so one would not notice crossing it, nor is there any thickness to it,” Igel added.

What about survival, even for a short time, in the frontier just inside the Kármán line? What would happen if you fell there without a specially designed spacesuit or accompanying oxygen tank? If you could reach it, could you breathe at such high altitude? And could birds even reach such heights?

“In principle, it is still possible to fly to the Kármán line,” Professor Igel noted. “However, in reality, animals cannot survive at altitudes above the “Armstrong limit”, which is about 20 km above Earth’s surface, where the pressure is so low that liquids in the lungs begin to boil.”